SPACE Ilford, 29 February 2020

‘This day will begin with a practical session of developing your presentation skills and techniques for effective communication. We will then look at the different economies and strategies that exist to support artists and artistic development, followed by a session around crowdfunding’.

The first LCN day was excellent, not only for the substantive content but also for being able to get to know other artists working in the area. I want to make some quick notes about the sessions, focussing on aspects of particular relevance to my current work and thinking about what I might do after the MA.

Introduction to SPACE – Persilia Caton, Exhibitions Curator, SPACE

Persilia was able to give us insight into the process by which the work for the first exhibition (by Lindsey Mendick) was selected through an open call process and how the gallery worked collaboratively with the artist. A key factor was engagement with the local community, and the ability to ensure both that the process of producing the work was of value, and that the outcome is a worthwhile and engaging exhibition. In particular, it was interesting to see how the work from the workshops (making work in clay with elderly people from the area with no prior experience) fed into the exhibition. The process also allowed the artist to experiment with new ways of working, and for participants to gain new skills and interests. The central theme for the exhibition (advice that you wish you had been given and taken, inspired by Baz Luhrmann’s Sunscreen), was clear and relatable.

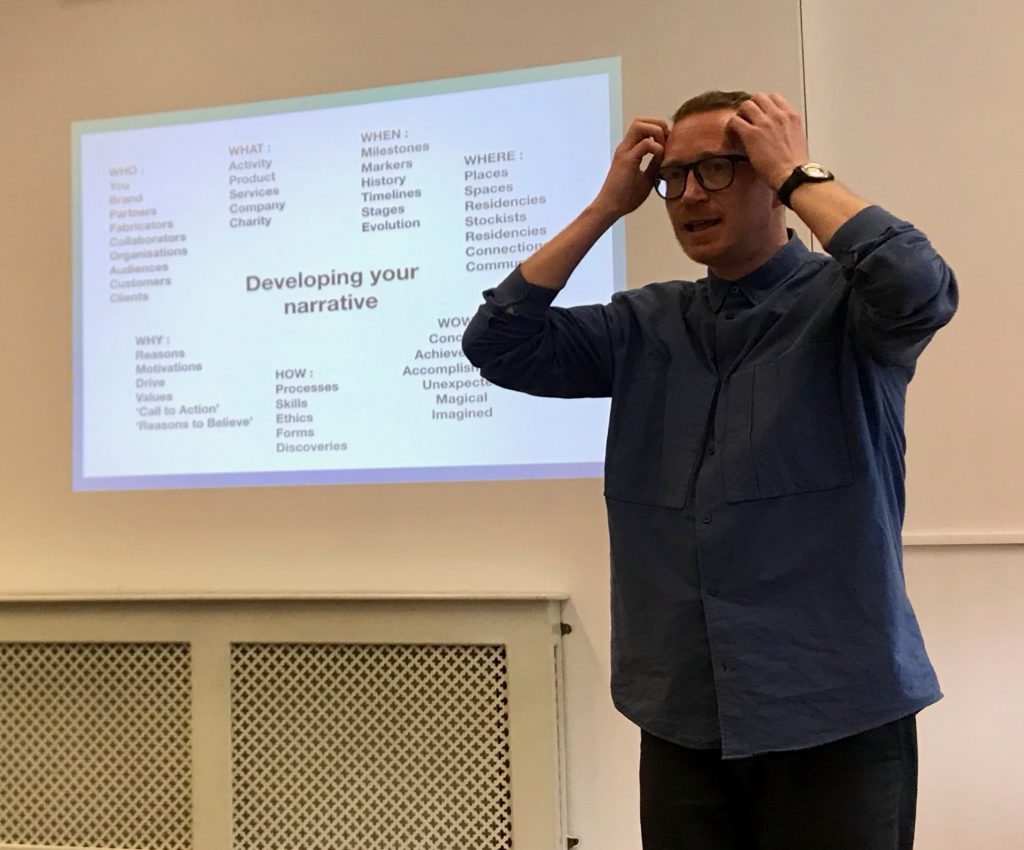

Presenting Yourself – Alex Evans

Good opportunity to get to know other members of the group and learn about Alex’s practice (which spans community focused work in east London and his own drawing based work). One of the communication activities involved describing a Lego construction to a partner who had to construct it solely on the basis of the description, exploring the need for a common language. This was reinforced in relation to describing our own practice to different audiences and for different purposes.

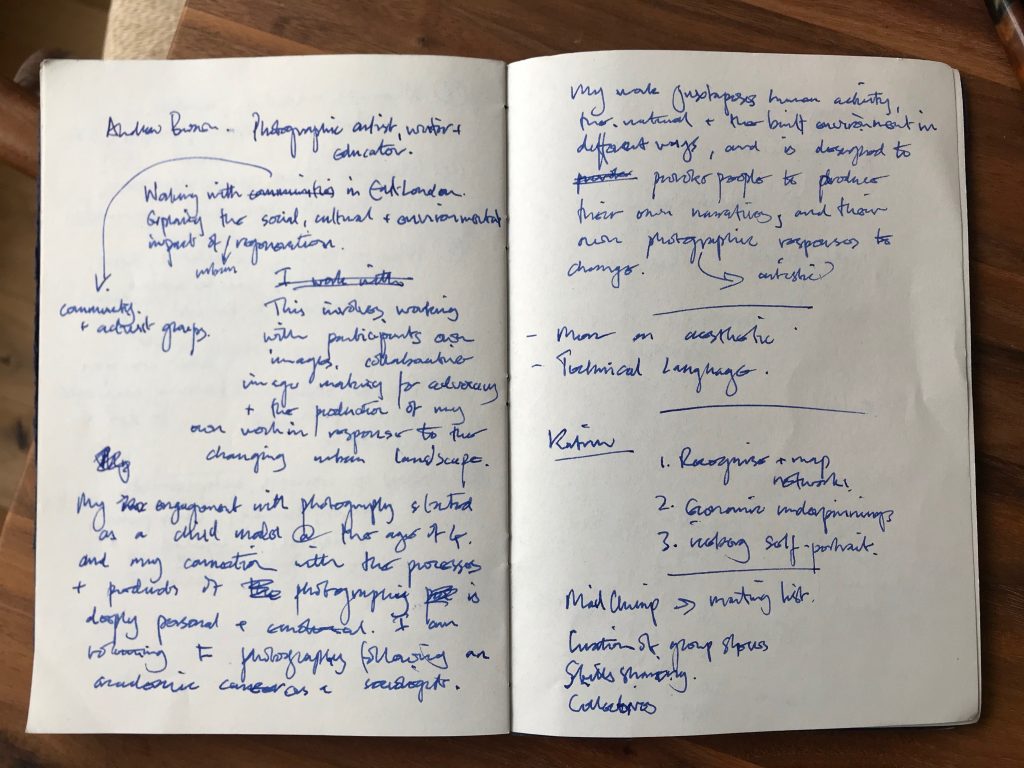

Alex introduced the Who (you, brand, partners, fabrications, collaborations, organisations, audiences, customers, clients), What (activity, product, services, company, charity), When (milestones, markers, timelines, stages, evolution), Where (places, spaces, residencies, stockists, connections, communities), Why (reasons, motivations, drive, values, ‘call to action’, ‘reasons to believe’), How (processes, skills, ethics, forms, discoveries), Wow (concepts, achievements, unexpected, magical, imagined) structure and we prepared one minute statements to share and discuss in groups of three (see below for mine).

The framework provides a structure and set of prompts for production of accounts (for instance, and artist or project statement) that can be adapted to different audiences (by, for instance, shifting focus, realigning priorities and changing language). It can also be used cyclically and a different levels in the same account, for instance to describe practice in general and the details of a specific project or a particular work.

Mapping and Strategising your Networks – Kathrin Böhm

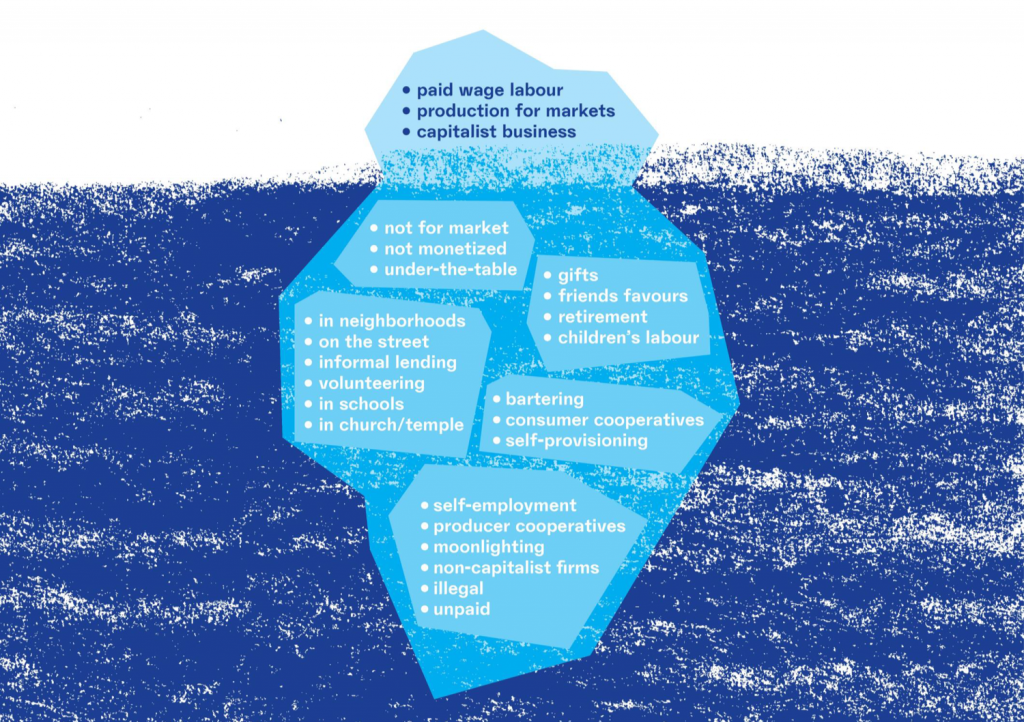

In this session we (i) identified and mapped out our networks; (ii) looked at the economic underpinning of artistic practice; (iii) considered an ‘iceberg self-portrait’.

The network mapping helped me to think about the relationship between my prior (academic) work and my current (artistic) practice, and the manner in which networks relating to these different domains might be mutually supportive. For me this is a matter of bringing my artistic and photographic work to a state of relative maturity, and keeping in mind how the work produced (and the processes and contexts of production) might constructively draw on and feed into my academic work and networks (for instance, in forming partnerships between academics and artists in the development of community relationships around UCL East). It was particularly productive to be able to put artistic practice at the centre of the network diagram. Kathrin emphasised the power of working as a collective.

Katherine Gibson’s (2014) iceberg metaphor was used in considering the economics of artistic production. This acknowledges that visible practice is supported by a greater volume and diversity of invisible activities (both personal and institutional). This led to a consideration of the diversity of forms of and audiences for art, and Stephen Wright’s concept of ‘usership’ rather that spectatorship, emphasising a need to be clear about how art is used in different contexts and by different communities. This relates to the manner in which I am using different forms of photography, and using photography in different ways, in different parts of my project (for instance, in activism and as a collective activity). Similar ideas are put forward by Arte Util (useful art); I will explore these further in the critical review of practice, in clarifying the relationship between the components of my project, and, in particular, the positioning of the outcomes of the FMP (as a subset of a wider programme of activities). Returning to the iceberg metaphor, we considered Gregory Sholette’s (2011) application of the idea of dark matter – the stuff that holds the market together but is not readily visible – and where in our own practice we might identify the ‘visibility’ line. Art viewed in this way is special (as a particular form of activity) but not other (set above or apart from everyday activity), resembling Laruelle’s notion of ‘non-philosophy‘.

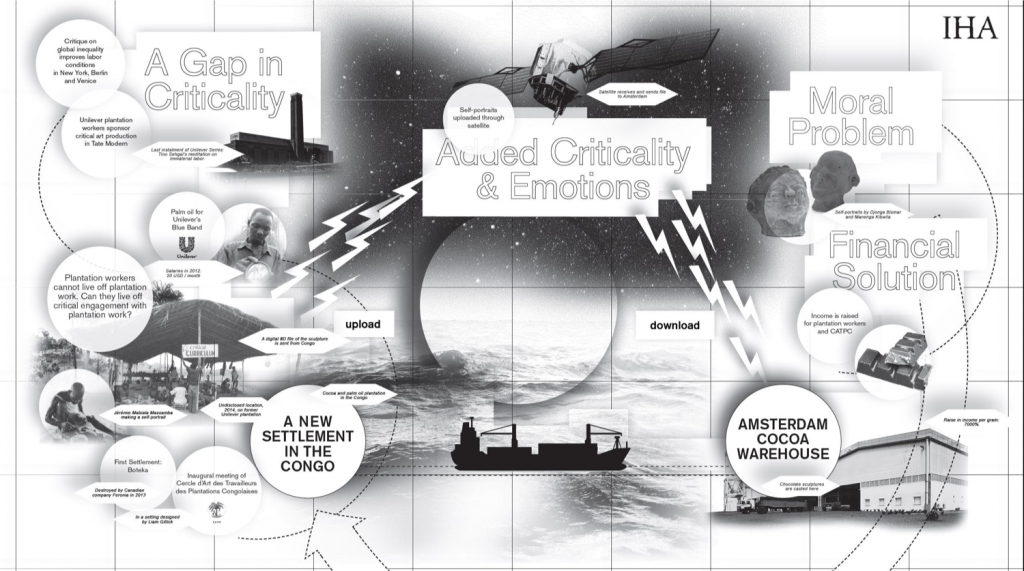

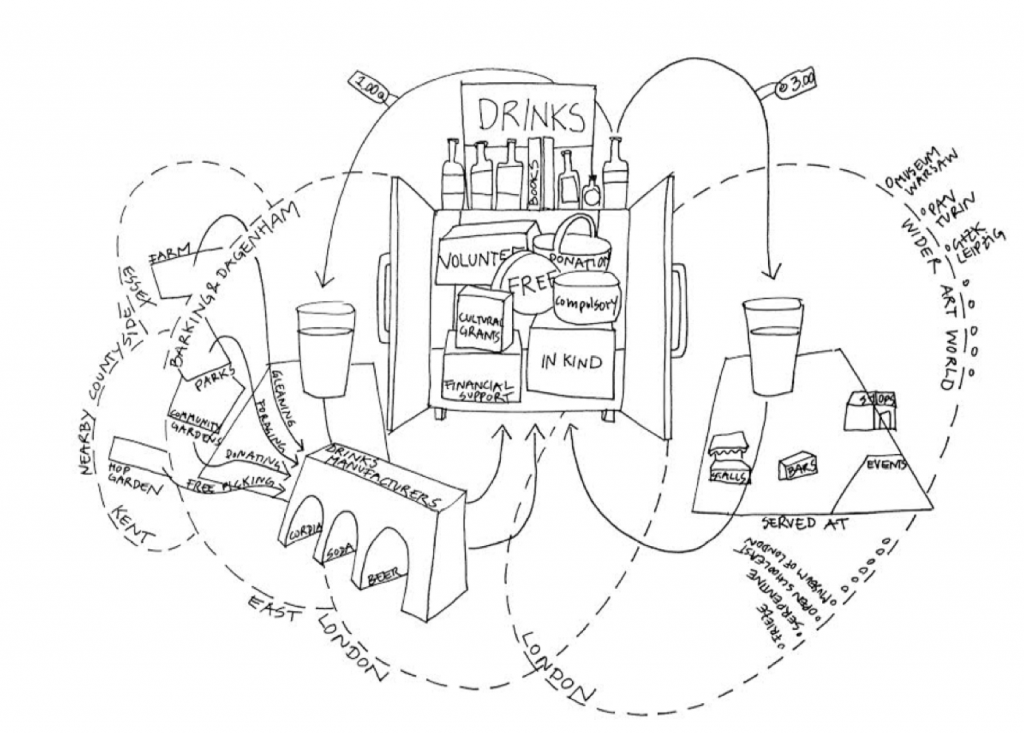

We explored diagrammatic forms of representations of relationships between activities, like those produced by the Institute for Human Activities.

These are similar to the diagrams produced by Brett Bloom and Nuno Sacramento. Kathrin has produced a diagram to represent how Company Drinks is positioned artistically and economically.

This session was particularly important for me in (i) helping to think through alternative forms of relationship between art and everyday practice, particularly through the idea of ‘usership’; (ii) thinking through how I can use visual means to describe the relationship between the components of my work (for instance, in providing a ‘visual index’ in my FMP pdf submission).

Crowdfunding – Tamara Stoll

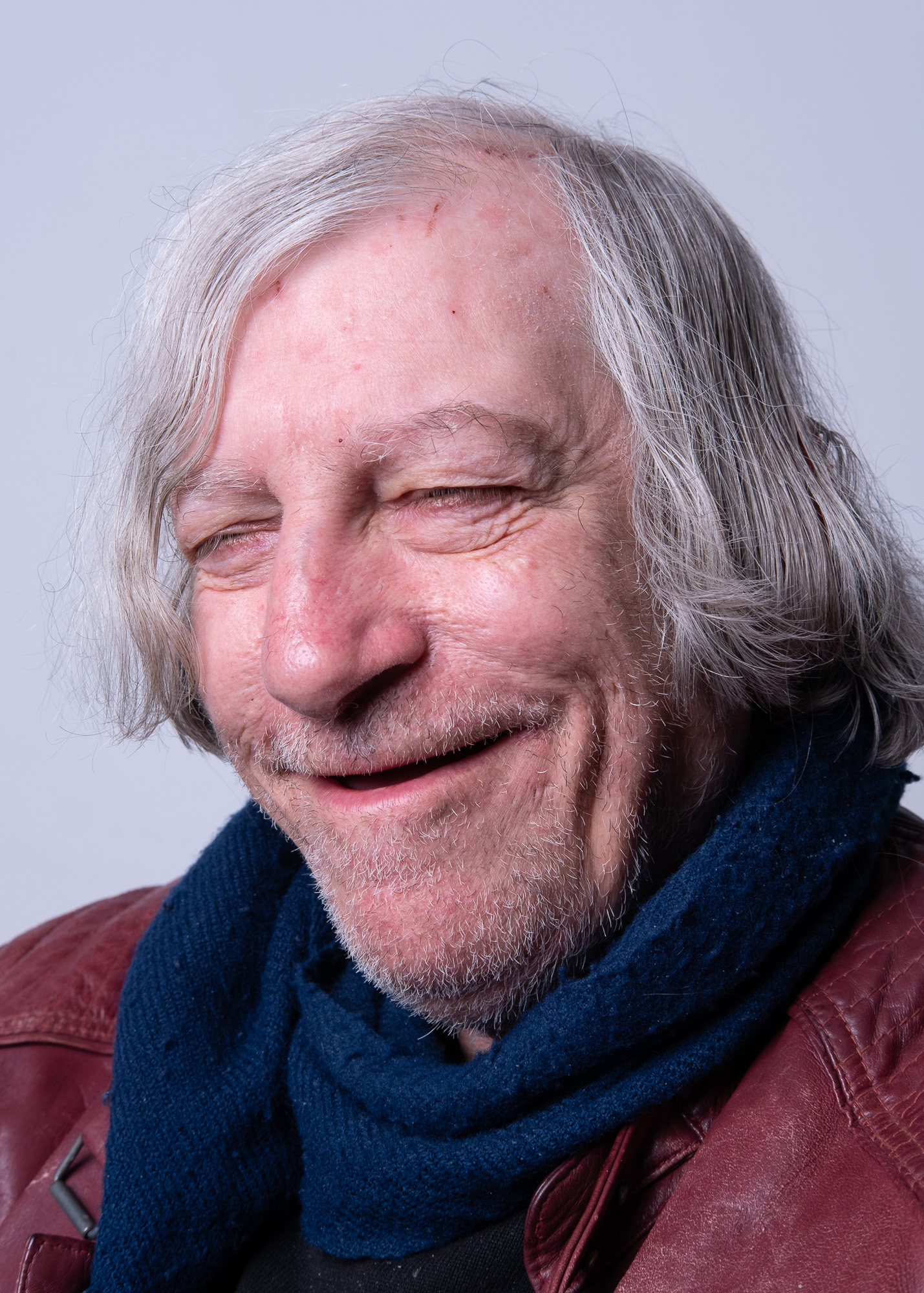

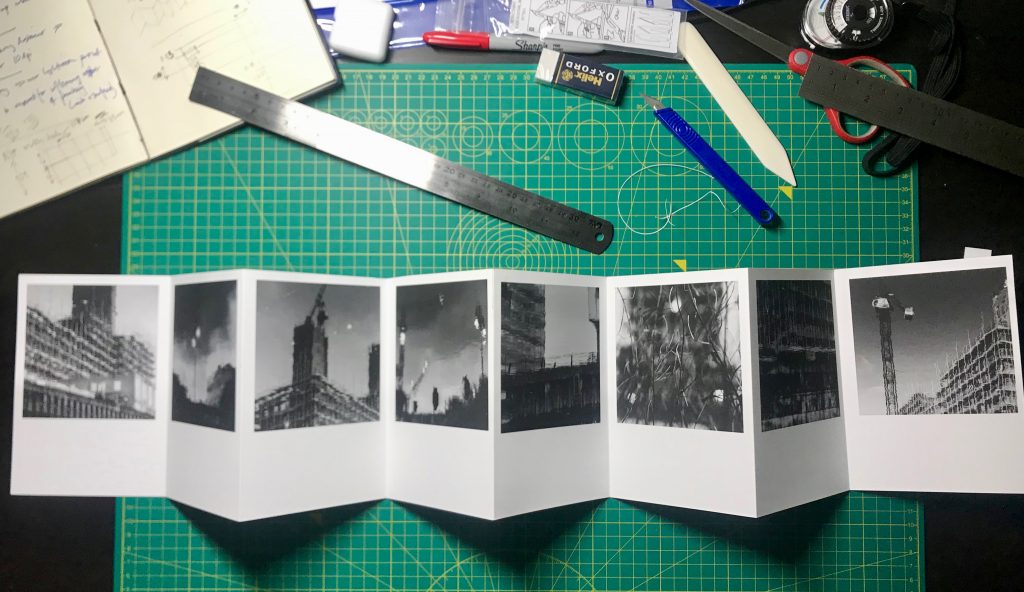

Tamara mapped out how she moved from the production of a book dummy for her Ridley Road project (8 years and 150 colour images) to publication, and how she used crowdfunding to fund the print run. The project stemmed from identification of a gap in the Hackney archives around the history of the market, and evolved into a site specific, collaborative project concerned with ‘streets and the people who make the streets’. Centerprise was an important influence (in both the publication of local writing and as a place to meet). As in my own work, building trust among the community was important, and she took on the informal role of campaign photographer for the Save Ridley Road campaign, organising workshops and exhibitions. She uses a TLR on a tripod to make the portraits, which quickly distinguishes her from the opportunistic street photographers who are not particularly welcome in the area.

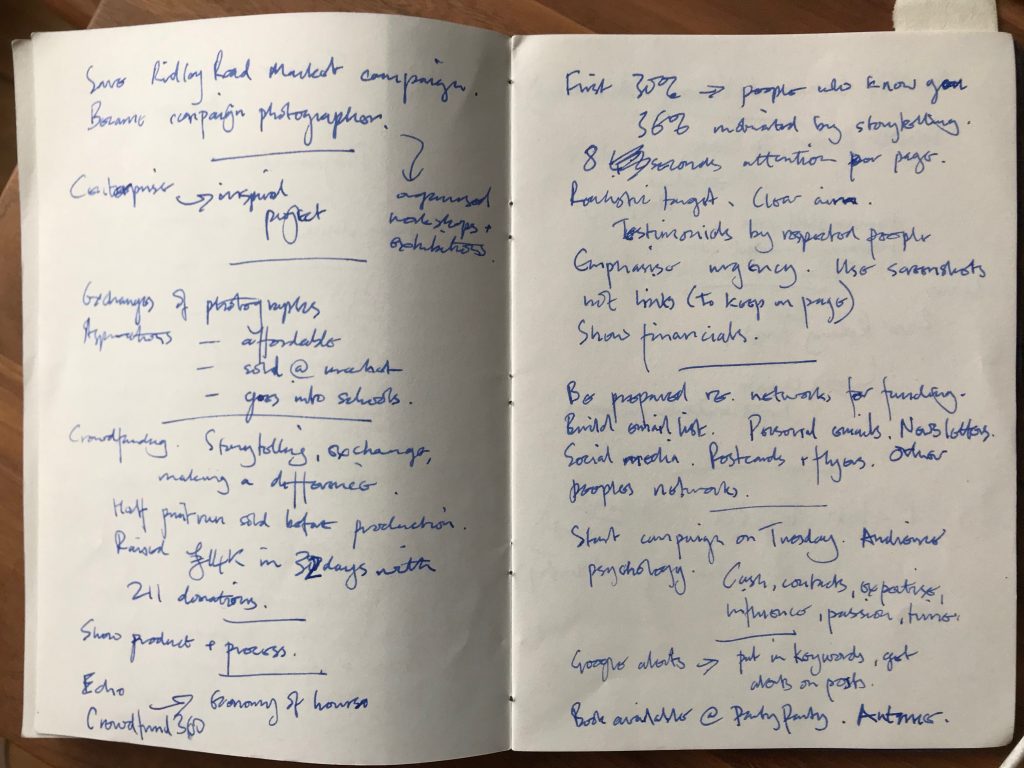

Lots of insights into Crowdfunding – see notes below (and pdf provided by Tamara).

The major insight for me, however, was into Tamara’s work, and resonances with aspects of my own work. In all, the day provided a number of strands to follow up, particularly around relationship between the community engagement aspects of my project and my own work

References

Gibson-Graham, J. K. 2014. ‘Rethinking the Economy with Thick Description and Weak Theory’. Current Anthropology 55, S9: S147-153. doi:10.1086/676646. [Accessed March 7, 2020].

Sholette, G. 2011. Dark Matter : Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture. London; New York: Pluto Press.

Wright, S. 2014. Toward a Lexicon of Usership. Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum. Online at https://www.arte-util.org/tools/lexicon/ [Accessed March 7, 2020].