As a primary school teacher, I used to keep a collection of images (postcards, photographs, cuttings from magazines mounted on card, and so on) to act as a stimulus for imaginative writing. The task was to draw four cards at random, look at and think carefully about them, form a sequence, and then write a story that in some way brings the four images together. The story was a construct of the reader come writer, and not inherent in the images themselves. Close to forty years on, I find that photographers commonly state that through their images they are attempting to tell stories. At the level of intention, this makes some sense, in that, through engagement with the world they can make, select and sequence images in such a way to, they hope, convey a sense of related events, or a set of relationships or circumstances. The reader then has to reconstruct that narrative, or at least some kind of narrative, through their engagement with the images. The question here is, to what extent is this possible without some prior knowledge or experience of that which is presented in the images, or, lacking this, some set of assumptions about the lifeworld or circumstances being presented?

This bears resemblance to making sense of metaphors. In trying to convey some notion, for instance, of what a fraction is, I can say that a fraction is like a slice of cake. Yum. But what particular qualities of a slice of cake do I wish to invoke, and associate with a fraction, through the metaphor. We, you and I, as readers, clearly have a idea of what a fraction is, and in what sense it resembles a slice of cake. But without already having this, possibly only vaguely formed, notion, what sense can we make of the metaphor? And, beyond that, how prepared are we for the utility of that understanding to collapse when we start to try to do things like multiply and divide fractions (this is like no cake I have ever known). The point here is to raise the question of the extent to which storytelling through images can do any more than reinforce already existing understandings (or prejudices), that is, can only tell stories that we (as readers) already know, or think we know?

Rather than lead us down a dead end, we can turn this into a challenge. What might we do to produce images that have the potential to transform, challenge, enlarge or enhance the understanding of the reader (in a fundamental sense, not just giving detail or texture to existing knowledge, such as the knowledge of Russian dress gained by Barthes (1981) from engagement with William Klein’s Moscow photographs)? One approach might be to consider storytelling as the primary practice, and photographic images as a principal (and not necessarily sole) resource. We might also consider what, distinctively, photographic images (and different modes of presentation of these images) can add to the practice of storytelling, and how the different resources available to storytellers can work together, particularly in creating an experience that shifts us away from the familiar and subverts the habitual.

Juxtaposition of images provides one resource for constructing, or invoking, a narrative, for instance in Esther Teichmann’s installations . Looking at these, however, leads to me to turn the relationship between images and storytelling around again, and place both as alternative means of enhancing understanding or addressing the ineffable, and each can draw on the other to that end. The story need not act as an intermediary between the images and the affect.

References

Barthes, R. (1981). Camera Lucida. New York: Hill and Wang.

Esther Teichmann, http://www.estherteichmann.com

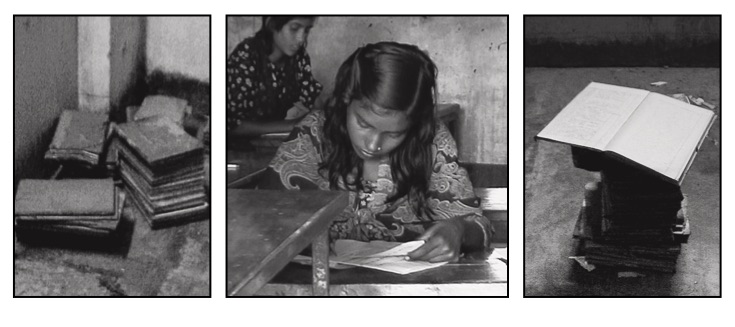

This is the image I have chosen to present (in addition to the ‘re-make’ images) for the Week One online seminar. The photographs were taken in a ‘hard to reach’ school (i.e, one that takes days to get to from the city, and, if it rains, can take much longer to get back from) in 2001 when I was working with the Ministry of Education in Bangladesh. The degraded black and white image makes it difficult to place the photographs in time. The images also have a painterly quality, which challenges the aspiration to mechanical (and now digital) veracity. The activity and objects depicted (books, schoolrooms and literacy practices) also span the history of photography (with mass schooling, based very much around literacy, numeracy and the regulation of behaviour, developing in the UK, through the school boards, from the mid-nineteenth century). Literacy is also particularly important for me; I didn’t learn to read until the age of 8, and when I did, it totally transformed my life, and has shaped my subsequent trajectory. In the case of Bangladesh, and other similar contexts, female schooling and literacy is particularly important. In presenting the images, I wanted to experiment with the triptych format, which invokes an earlier, pre-photographic (and pre-industrial) era in the west.

This is the image I have chosen to present (in addition to the ‘re-make’ images) for the Week One online seminar. The photographs were taken in a ‘hard to reach’ school (i.e, one that takes days to get to from the city, and, if it rains, can take much longer to get back from) in 2001 when I was working with the Ministry of Education in Bangladesh. The degraded black and white image makes it difficult to place the photographs in time. The images also have a painterly quality, which challenges the aspiration to mechanical (and now digital) veracity. The activity and objects depicted (books, schoolrooms and literacy practices) also span the history of photography (with mass schooling, based very much around literacy, numeracy and the regulation of behaviour, developing in the UK, through the school boards, from the mid-nineteenth century). Literacy is also particularly important for me; I didn’t learn to read until the age of 8, and when I did, it totally transformed my life, and has shaped my subsequent trajectory. In the case of Bangladesh, and other similar contexts, female schooling and literacy is particularly important. In presenting the images, I wanted to experiment with the triptych format, which invokes an earlier, pre-photographic (and pre-industrial) era in the west.