I have written earlier about the notion of ‘photographies’ rather than considering ‘photography’ as unified (or even unifiable) practice or discipline. Accordingly, I have divided my practice into a number of different domains of practice, each having its own intent, audience and means of dissemination/circulation (and outside this self-consciously photographic work, of course, use photography and photographic images in a variety of other activities). There are, however, a number of underlying concerns (about theory, practice and the nexus between these, for instance). Although I have described my project as having three levels of production and circulation of images/artifacts, there is no a priori hierarchy – these domains of practice (my own art, collaborative campaign image making, engagement with community image making) are just different contexts for the deployment of photographic image making (and therefore all contributing to my development as a photographer, and the development of my skills and understanding of the processes, practices, contexts and fields of photography).

Over the past week, I have made advances in all three domains (which I will describe in other posts). For the purpose of this reflection, I will focus on my own artistic practice. The aim of this work is to develop a distinctive means of exploring areas of material, social and cultural domains of human experience, for instance the impact of the process of urban regeneration on residents. The intent of the work is to examine the interaction between different interests in, experience of and aspirations for a particular place and the changes that take place over time. There is thus a need to bring time and place, and different subjective relationships to these dimensions, into the same space, through, for instance, juxtaposition within or between images and artifacts. To do this also entails a multi-modal approach. At this point in time, I am experimenting with images; ultimately these will be combined with sound, text, moving image, artifacts and other media in exhibition, installation and/or book form.

The principal audience for this work is others with a critical interest in arts-based practice and research and the contribution this can make to the critical understanding of human experience and engagement with the world. The audience would also include those who are interested more broadly in the issues I am exploring, or having overlapping interests from other disciplines and areas of practice. The audience would also include people directly involved in the contexts being explored (for instance, residents, developers, councillors, activists, in the case of urban regeneration), as well as those with a direct interest in the visual arts. At this point in time, I am engaging with people in a variety of communities in the evolution of the work.

For me, ambiguity is one of a number of strategies available in making images and juxtaposing them with other modes. If work is specifically aimed at examination of photography as a practice or field, I can see that ambiguity might be an intent in its own right. However, ambiguity without context is untethered from meaning: in making sense of the ambiguous image, the reader imposes their own context which, it might be argued, radically alienates the image from the maker. Ambiguity as a sole intent thus might give rise to a number of novel and engaging images, but ultimately will not provide the basis for an enduring and coherent body of work: that would require a broader conceptual base, and a corresponding (but not necessarily all encompassing) sense of direction.

Over the past week I have experimented with the overlaying of images, and in particular the exploration of multi-channel works. Although the aim has been to produce works in colour, some of the most satisfying images have been monochrome (working with monochrome images in three colour channels and then converting back into monochrome by de-saturating, or using a gradient map, at the final stage). The image below juxtaposes the built (fence) with the natural (macro plant images).

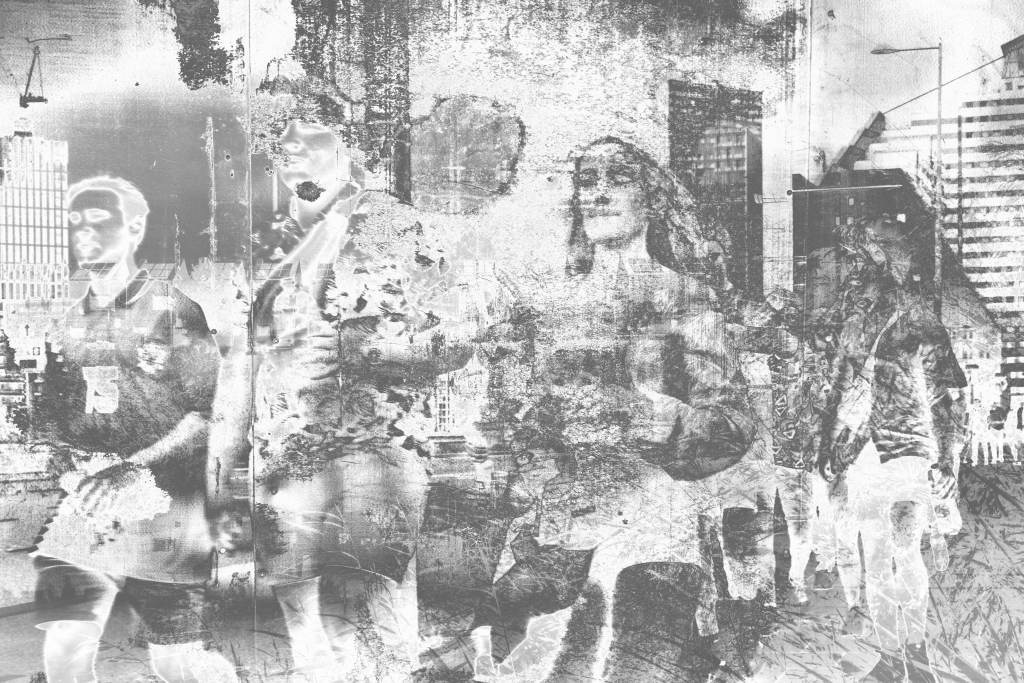

This image combines different scales of image taken in the same place (Stratford Station, from a train).

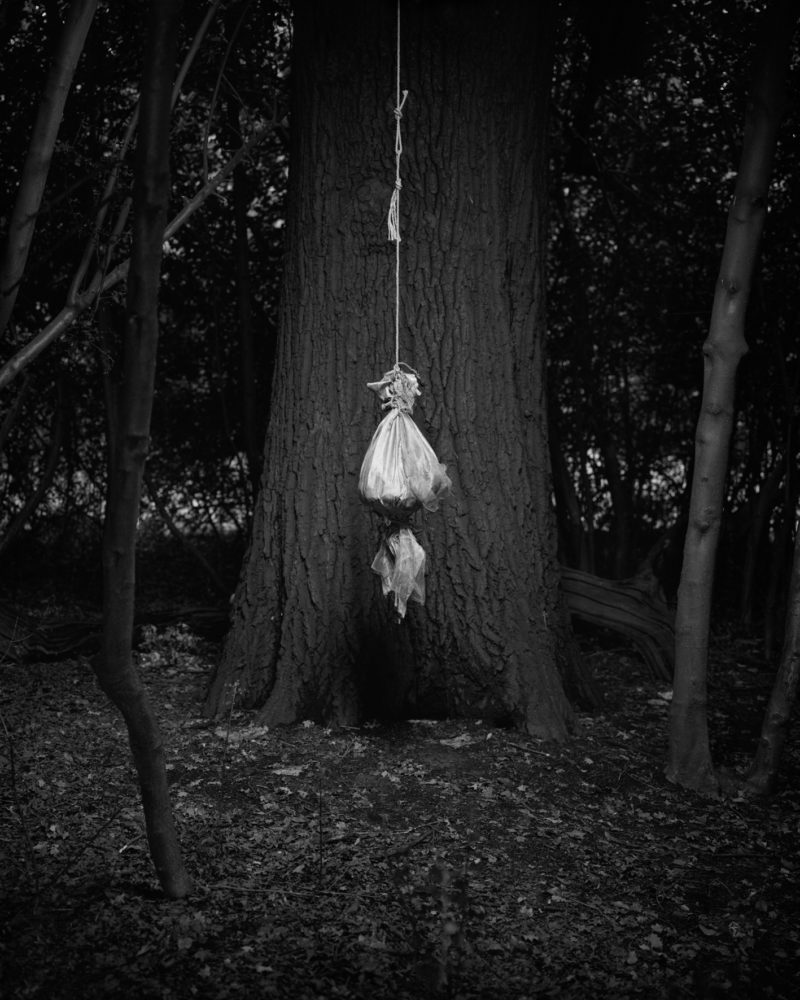

The form of the third monochrome image combines human forms in the built environment, with urban nature and a macro shot of a corroded surface.

In all cases the distinct and discontiguous (in time, space, scale, natural/human/constructed) are brought together in the same space, with the intent of produce an open text which invites interpretation. There are similarities, particularly the second image, with the work of Antony Cairns (who uses chemical not digital processes and has experimented with printing on aluminium plates and displaying images on Kindle screens).

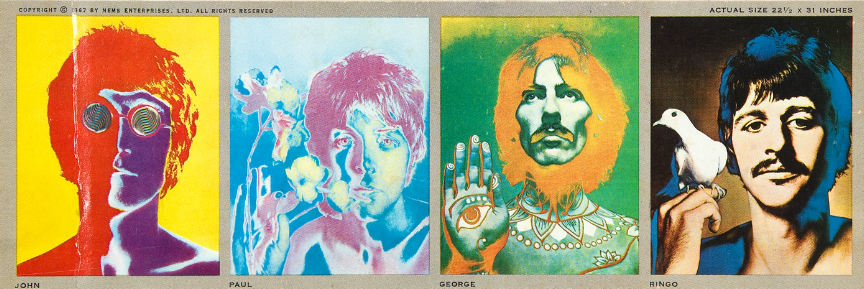

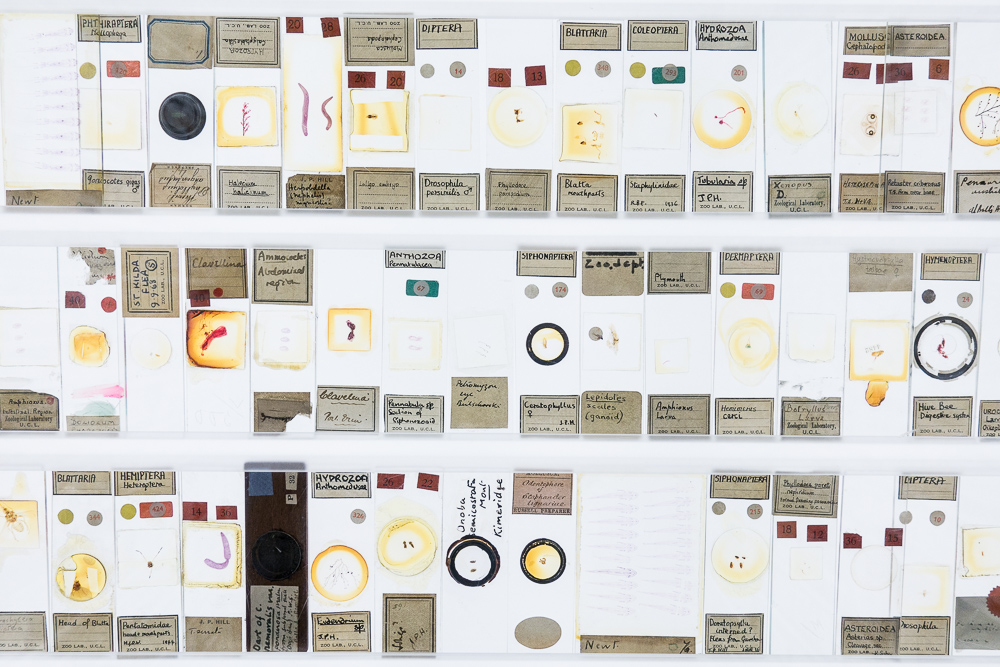

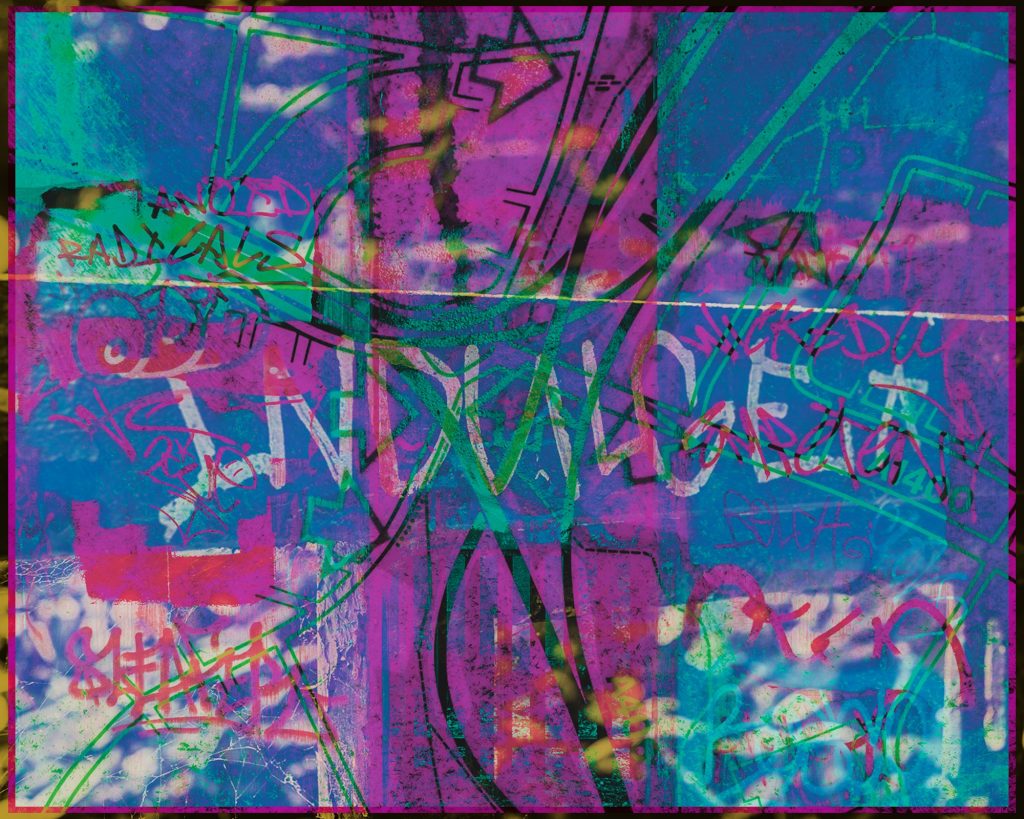

In the colour work, I have explored the use of existing images. The following three images are formed by overlaying images from the triptychs produced in the first module.

The final image combines a developer produced image of the future, with an image of construction in progress and an image of the natural landscape that is in the process of being ‘over-written’.

A monochrome version of the same image opens up an exploration of the affordances of colour and monochrome images in this context.

More experiments to follow …