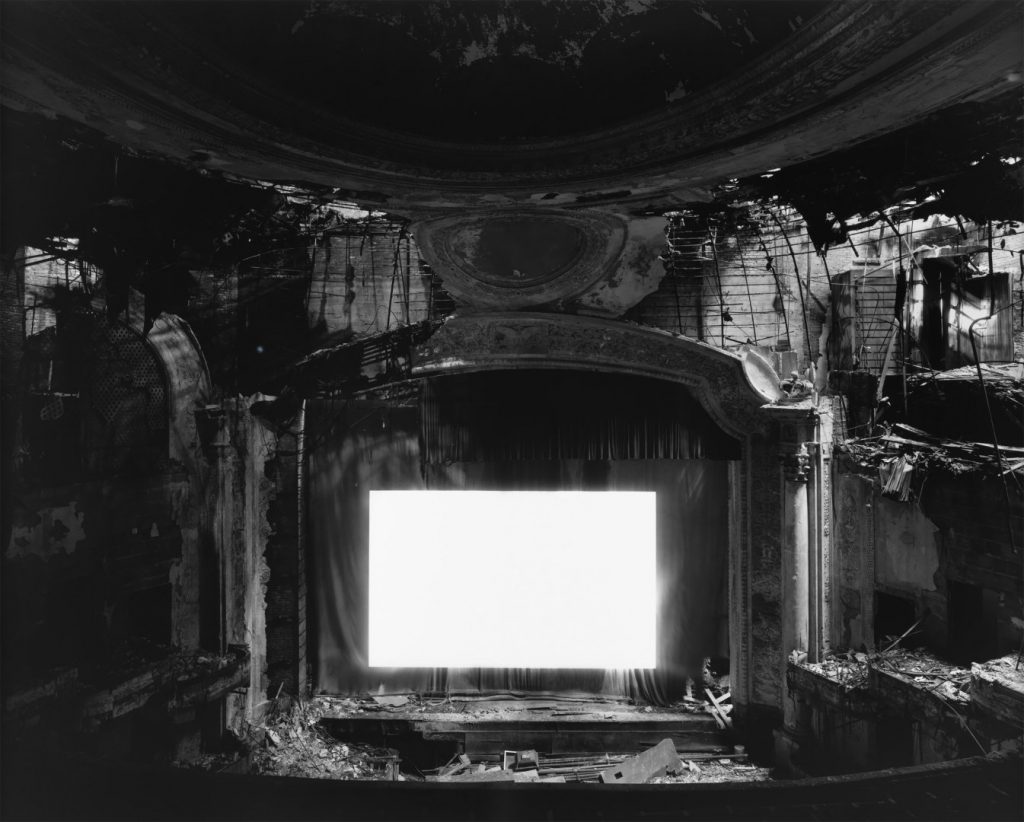

Sugimoto is a significant figure in contemporary photographic practice. From his New York studio, the Japanese born photographer has produced several series of photographs that are widely represented in major collections and regularly internationally exhibited. As an art photographer, he has been hugely successful, and has combined this with a range of architectural projects, multi-media installations, collaborations and public works. Notably, his work has a strong conceptual basis, as well as being technically highly accomplished (he works in monochrome with an 8 by 10 camera, producing very large prints, and relentlessly experiments with methods of producing images and prints). Conventionally, analysis of his photographic work has concentrated on the capturing and manipulation of time, and on the dialogue between eastern and western epistemologies. My analysis will draw on this valuable and insightful work, but will depart significantly in exploring Sugimoto’s photographic work in relation to post-humanist theory (that is, theoretical work that seeks to go beyond humanism, for instance work by Rosi Braidotti 2013, Donna Harraway 1991 and N. Katherine Hayles 1999). In particular, I will explore Jeffery Jerome Cohen’s (2017) notion of ‘midhumanism’ to sidestep a linear view of time in favour of the vortex, and to dispense with the seemingly inevitable grind of passage from pre-(x), to (x), to post-(x), where we languish waiting for a new episteme to gestate. The theoretically stultifying effects of this ‘progression’ are particularly marked in the analysis of photography, which having moved with tide of western theory away from its modernist origins (as a representational technology), consigns the ever-increasing population of art-photographers to the post-modernist hopper (for sorting and labelling).

It should come as no surprise that Sugimoto started his professional life as an antiques dealer (and continues to deal in antiques to this day), given that, I would argue, his work synthesises antiques from (and thus, in terms of cultural commodities, adds value to) the present. For instance, Sugimoto claims that his Seascapes Series seeks to show parts of world as the ancients saw them (Sugimoto, 2018a). He seeks out fragments of the present that can be claimed to be invariant across the human era (and, as Sugimoto observes, time is itself a human construct), and represents these in investable, portable (see Henning 2017, for exploration of the portability of photographic objects) and tradable form (limited edition large format prints). The blurred photographs of modernist buildings in the Architecture Series decouple the aspirations of the architects from the image, and allow the buildings to live on as a cultural commodity without their modernist baggage.

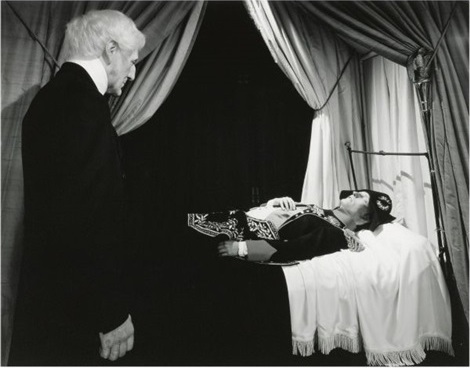

As Molinari (2015) observes, the blurring seeks out an enduring core to the buildings, which are thus allowed to escape the ravages of time. In no sense, then, is the photograph a record of a point in time; it is in not a representation of what the building once was, or will ever be, except in this particular rendering. For me, the photographs in this series are durable cultural artefacts (and thus commodities), synthesised in the present from a physically and conceptually unsustainable past. Related arguments can be made about other series. The printing of Fox Talbot paper negatives finds in the present lost moments from the past that were never realised in positive, material form, but remained latent (in a process akin to way that Sugimoto as antique dealer scours markets for artefacts). The Diaorama and Waxwork photographs allow imagined and constructed pasts to be rendered portable and available for exchange in an enhanced indexical form (a photograph), invoking and subverting the modernist aspirations for mechanical representation. Whilst Sugimoto’s account of his own work differs in many ways from my reading, he clearly recognises the subversive potential of his work, and the ironic dimension to not just stopping time, but bringing the dead back to life and turning time back on itself.

‘In my picture, Wellington seems to have come back to life, while Napoleon remains very much dead. I know it is unlikely, but should I win a place in the pantheon of great artists, I have this crazy fantasy of someone adding a wax figure of me taking a picture of the two great men with my large-format camera to the existing scene!’ (Sugimoto 2015: 28).

My positioning of Sugimoto in relation to post-humanism is based on a reading of his commentaries on his own work (in print, for instance Sugimoto 2015, and on film, for instance, Nakamura 2012, Sugimoto, 2011, 2018a, 2018b). In his writing on Fox Talbot, which includes reflection on his own photographic work, such as the Photogenic Drawings made from Talbot’s paper negatives, and his experimentation with static electricity in the Lightning Fields series, Sugimoto celebrates Talbot’s humanism. For instance, he notes with surprise that Talbot studied ancient languages, conducted research on Babylonian cuneiform characters and Egyptian hieroglyphs, and was translating Macbeth into Greek verse.

‘Talbot, I realized, had a deep understanding of the spirit of those ancient civilizations, when man (sic) first lifted himself out of ignorance’ (Sugimoto 2015: 34).

Sugimoto’s work is strongly humanist in its orientation, having collapsed time, extracted the past out of the present, projected it into an unknown future, and related his images to a supposed invariant human spirit. Central to this orientation is recognition that time is a human construct, and a sense of the passage of time requires a human consciousness. The desire to stop time, which he sees both in the work of the founders of photography and in his own work, is thwarted by that consciousness: while there are humans, there will be time, and our attempts to stop time will always be in time. He states that

‘The day when mankind will realize our deep-seated desire to bring time to a stop is coming inexorably closer. Time exists only through the agency of human perception. Only when mankind vanishes form the earth can we truly claim to have halted time’s progress. It is not long now.’ (Sugimoto 2015: 40).

In this distinctly post-humanist statement he recognises both the limitations of the aspiration to stop time, and the fruitlessness of the desire to produce timeless artefacts. Sugimoto has taken this further in his 2014 show at Palais de Tokyo in Paris, Aujourd’hui le monde est mort (Lost Human Genetic Archive), in which he imagines the end of the world. He claims ‘Imagining the worst conceivable tomorrows gives me tremendous pleasure at the artistic level. The darkness of the future lights up my present.’ (quoted in Searle 2014).

Whilst the Seascapes Series might help us to imagine we see the world as the ancients saw it, it will not enable us to see the world as it is, or was or ever will be. We, ourselves, are in, and entangled with, that world, and can only imagine (assisted by photographic or other technologies) standing apart from it (in the same way we can only imagine photographing Wellington viewing the corpse of Napoleon, or a moment that captures the duration of a film). Jeffery Jerome Cohen’s idea of midhumanism provides an interesting and potentially productive way of understanding, and appreciating, Sugimoto’s work. In this, human-centric narratives of history (that everything has a birth, a life-course and a death) are abandoned (Cohen 2017). The human is entangled with, not apart from, the world (though may aspire, and continue to attempt, to rise above the world). The human is enmeshed in and continuous with the world, and in striving to manage that embeddedness ‘all kinds of becomings are possible, and are not harnessed to trajectories of commencement and termination’ (Cohen 2017). This is the ‘midhuman, where human is difficult to tell from world, macrocosm and microcosm entangled rather than parallel’ and where we have to ’embrace the problem of human middleness, explore its implications, stay with it, stay with the world, think rigorously about the unexpected environmental consequences of human actions, midhumanism’ (Cohen 2017).

Sugimoto’s work, in its subversion of time, does not have, or exist within, a life-course enclosed by commencement and termination, except in the invocation of the end of humanity. The various series of photographs do not constitute a progression, and, although distinct, the series remain open, with the possibility of adding further images. His experiments (for instance, with static electricity) do not represent progress towards more advanced knowledge, but rather resonate with and supplement the experiments of the founders of photography. The images subvert the linearity of time and thus thwart human-centric western enlightenment, and modernist, aspirations, whilst potentially enriching our sense of entanglement and continuousness with the world.

In looking to my own practice, Sugimoto’s work is instructive in its conceptual clarity, and the manner in which successive projects develop rhizomatically from earlier work. From this, he is able to construct an overarching, unifying account giving the total body of work a high degree of coherence, with each series having a distinct visual (in terms of both the formal composition of the images and the method of production) and conceptual identity. Sugimoto has also been able to construct an exemplary contemporary (distinctly male) artistic persona, contextualising and positioning his work (artistically and commercially) and creating a network of interlinked activities which cross seamlessly between western and eastern cultural practice, each casting a light on the other.

References

Braidotti, R. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Cohen, J.J. 2017. ‘Midhumanism’. Critical Posthumanism. Available at:

http://criticalposthumanism.net/genealogy/midhumanism/ [accessed 30/12/18]

Searle, A. 2014. ‘Hiroshi Sugimoto: art for the end of the world’. The Guardian, 16th May [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/may/16/hiroshi-sugimoto-aujordhui-palais-de-tokyo-paris-exhibition [accessed 30/12/18]

Haraway, D. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge.

Hayles, N.K. 1999. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Henning, M. 2017. Photography: The Unfettered Image. London: Routledge.

Molinari, L. 2015. ‘Space: timeless architecture’. In Hiroshi Sugimoto, Stop Time. Milan: Skira, 22-40.

Nakamura, Y. 2012. Memories of Origin: Hiroshi Sugimoto. [Film]. Available at: https://youtu.be/NhZJF4IPXcw [accessed 30.12.18]

Sugimoto, H. 2011. Becoming an Artist. Art21, Episode 141. [Film]. Available at: https://youtu.be/JCsbxVCdDtA [accessed 30.12.18]

Sugimoto,H. 2015. Stop Time. Milan: Skira.

Sugimoto, H. 2018a. Between Sea and Sky. Interviewed by Haruko Hoyle at Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, June 2018. [Film]. Louisiana Channel, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Available at: https://youtu.be/JWh4t67e5GM [accessed 30.12.18]

Sugimoto, H. 2018b. Advice for the Young. Interviewed by Haruko Hoyle at Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, June 2018. [Film]. Louisiana Channel, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Available at: https://youtu.be/TvO2WL-jGac [accessed 30.12.18]