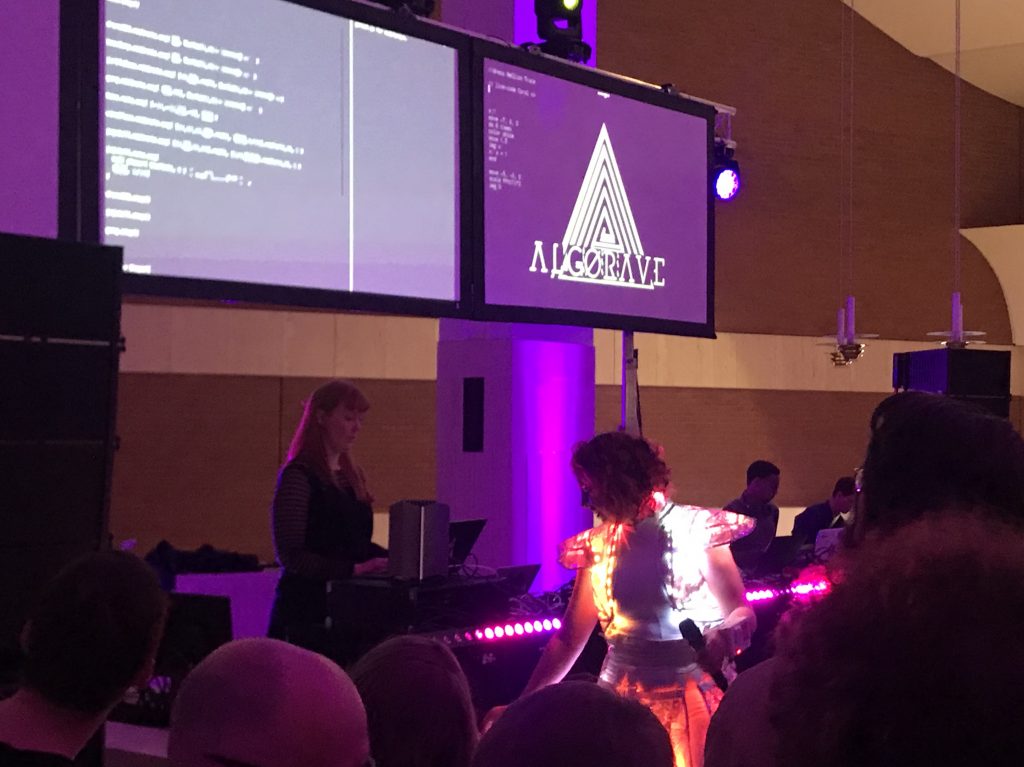

While I was working on the images for the work in progress portfolio, I produced short animations, principally to illustrate the process of channel mixing that I had developed. After sharing and discussing these with Jesse and Michelle, and others on the course, I decided to include them in the portfolio. To be included, they have to do more than illustrate a process, so I have edited them to fit with the theme and setting of each series in the portfolio. These are the three resulting one minute animations.

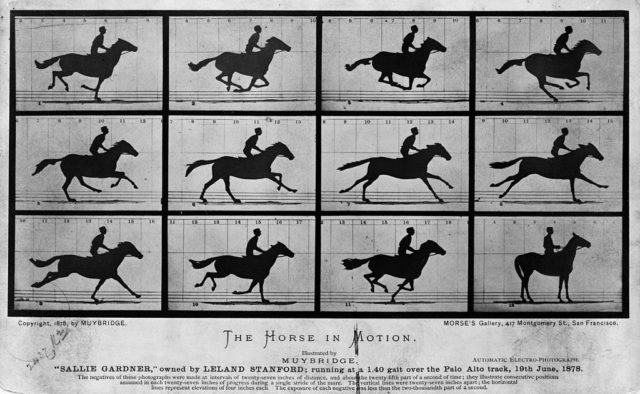

Doing this has also led me to reflect on the wider photographic context for this work. I am using a method similar to that used by Muybridge in his exploration of human and animal movement. ‘Horse in Motion’ (Muybridge, 1878) shows 12 consecutive images of a horse running, which can be combined, using a stop-motion style technique. This work is commonly seen as providing the inspiration for the development of motion pictures.

The juxtaposition of successive photographs of animals and humans in movement reveals what could not be perceived by a human viewer in real time. The initial motivation for ‘The Horse in Motion’ was to discover if at any time all four of the horse’s legs were off the ground. There are two levels of fiction here. Firstly, each image is a fiction, a point of seemingly static transition in fluid movement created by the act of photography: though presented as individual images, no point in the sequence can exist independently of the others, apart from as an image. Our resultant understanding of motion is a product of the translation of temporal into spatial relations. Secondly, by combining the photographs into an animation, perceptual transitions are created (intermediary states, between one photograph and the next) that do not have any corresponding material image. This is particularly the case with my animations, where the process of dissolving one image into another creates images that I have not produced. Here we are dealing with perceptual, in Muybridge’s animation, and digital, in my animation, artefacts, which challenge claims (and desire) for the indexicality of the photographic image.

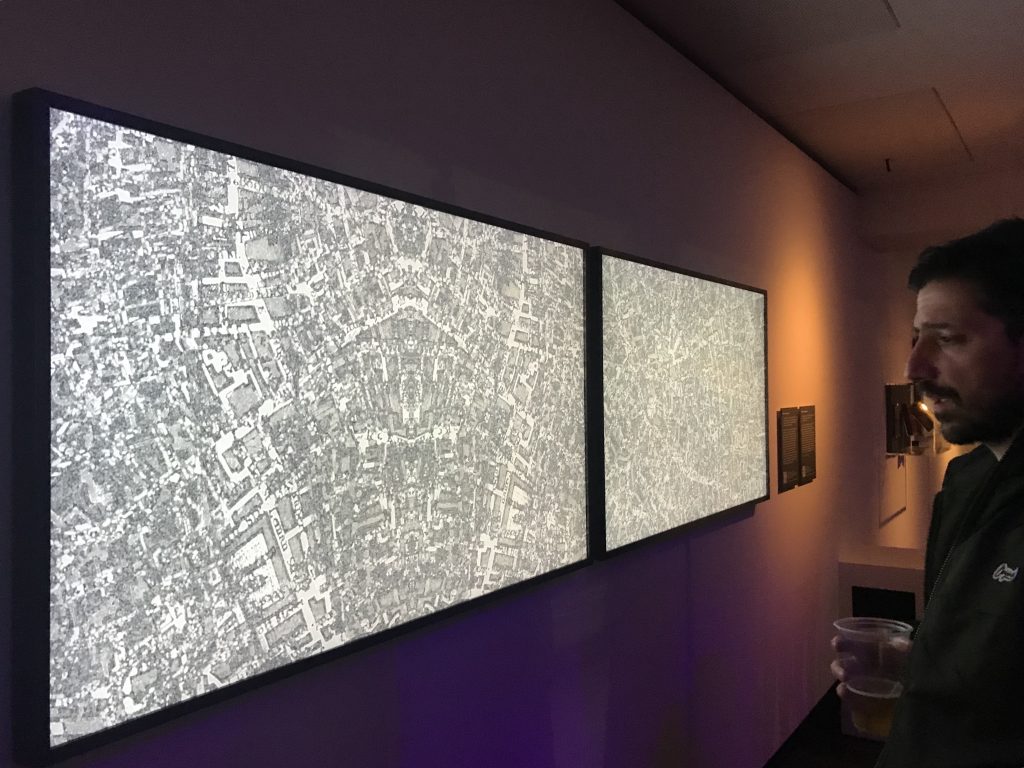

This is explored by contemporary artists using photography. Catherine Yass, for instance, has explored the passage of time and its relationship with space. In her early work, Yass has made successive positive and negative images of the same scene and overlaid these on a light box. Small differences in time (between exposures) are made visible in this process. She sees the process of overlaying as disrupting sense of space and position.

More recent work has involved digital video from a drone moving around an object, and the slowing of the video to one eighth speed whilst maintaining frame rate, which forces the creation of new imaginary moments through digital interpolation (like the channel mixing composites, where interaction between layers produces images as fictions, and the production of animations of these images, which produces new images as transitional artefacts).

She has also looped and manipulated the Harold Lloyd clock scene from the 1923 film Safety Last to play with notion of time and direction of the flow of time. Most recently, she has left 4×5 sheet film in the street to decay and displayed the results on a lightbox to explore time and decay.

Through my own composite images I aim to explore changing notions of time. As Yass (2017) states, photographs, and the critical juxtaposition of moving and still images, offer exciting ways of exploring this.

“The time in the photograph, the movement within and between two photographs as well, is so conceptually different from a moving image and yet they’re a tiny millimetre apart. I started filming things but slowing them down by incredible amounts so they were almost still. That was a little jump into the moving image and I got more excited by it” [online, no page]

This ambiguous relationship between still and moving image, and the capability to produce movement from still images and still images from moving images, and to manipulate this, demonstrates the power of photography to explore the nature of time and its relationship to space and place. Where my work, and that of Yass and others, differs radically from earlier (say, futurist) artistic explorations of time, movement and the still image is that I am not trying to represent movement or the passage of time in a still image, but to disrupt time and explore conceptions of time. The animations are part of that exploration. A key difference between the still images and the animation is the agency that is given to the viewer. The author grasps control of sequencing and the temporal juxtaposition in the animation (but not, of course, its meaning, only an influence on its meaning potential), whereas sequencing and juxtaposition of individual still images is in the hands of the reader (though, again, this can be subverted in, for instance, book format). The form of Chris Marker’s film La Jetée (1962), composed almost entirely of still images, explores this relationship, and it is notable that Marker preferred to describe La Jetée as a photo novel, rather than a film (Hinckson, 2014).

References

Hinckson, J. 2014. “There’s No Escape Out of Time”: La Jetée. Tor.com, Macmillan. Online: https://www.tor.com/2014/11/03/theres-no-escape-out-of-time-la-jetee/ [accessed 20.04.19]

La Jetée. 1962. Directed by Chris Marker. France: Argos Films.

Muybridge, E. 1878. The Horse in Motion. San Francisco: Morse’s Gallery

Safety Last. 1923. Directed by Fred Newmeyer and Sam Taylor. USA: Hal Roach Studios

Yass, C. 2017. Quoted in British Journal of Photography, ‘When does photography stop being photography?’ 6th April 2017. Online: https://www.bjp-online.com/2017/04/installation-image-manipulation-and-performance-art-when-does-photography-stop-being-photography/ [accessed 20.04.19]