My interest in the production of collections/archives stems from my desire to avoid the creation of strongly framed narratives in favour of potentially more open texts, which provide opportunities and resources for the audience/user to develop their own narratives and understandings from engagement with the work.

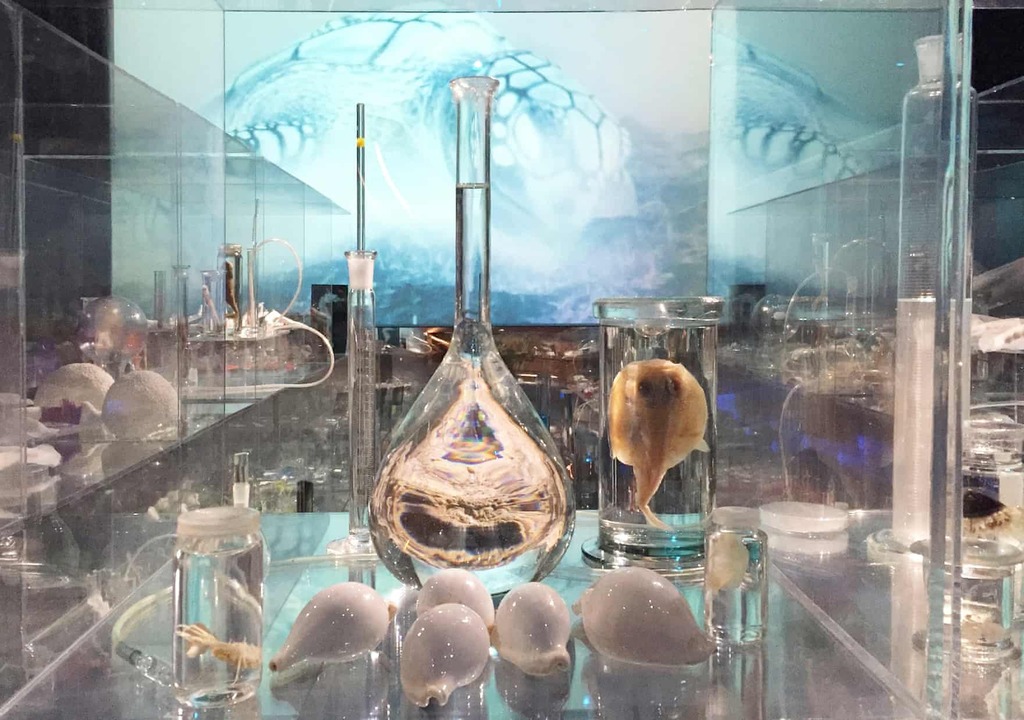

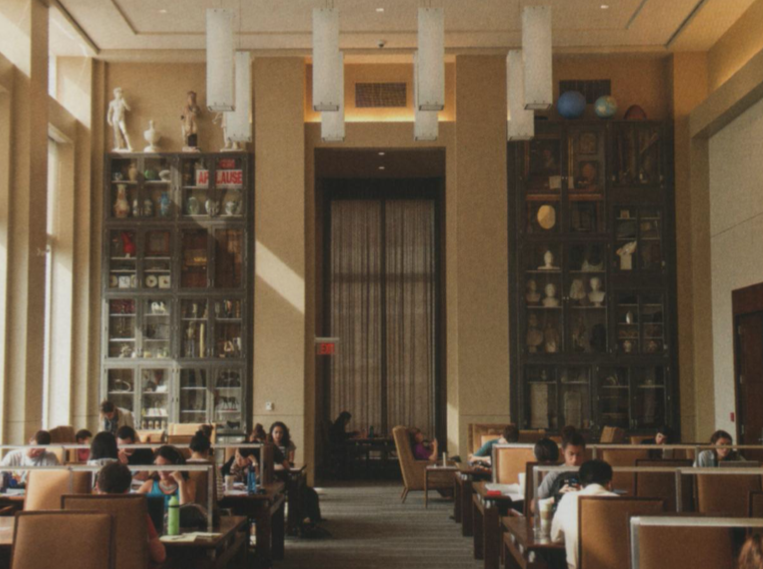

In a presentation at the Nasher Sculpture Centre, Dion (2013) describes the primary focus of his work as being ‘the history of natural history and the representation of the natural world’, and consequently many of his projects have been in collaboration with institutions that share this interest, such as museums, zoos and botanical gardens. In the same presentation he specifically frames his core question as ‘How is it that certain things get to be called nature at any particular time by a particular group of people?’. As Talasek (2014) observes in discussing Dion’s permanent exhibit at Johns Hopkins University (Figure 1), this resonates strongly with the central concerns of poststructuralist epistemology and particularly approaches to knowledge influenced by the work of Michel Foucault (see, for instance, Foucault, 1966; 1969).

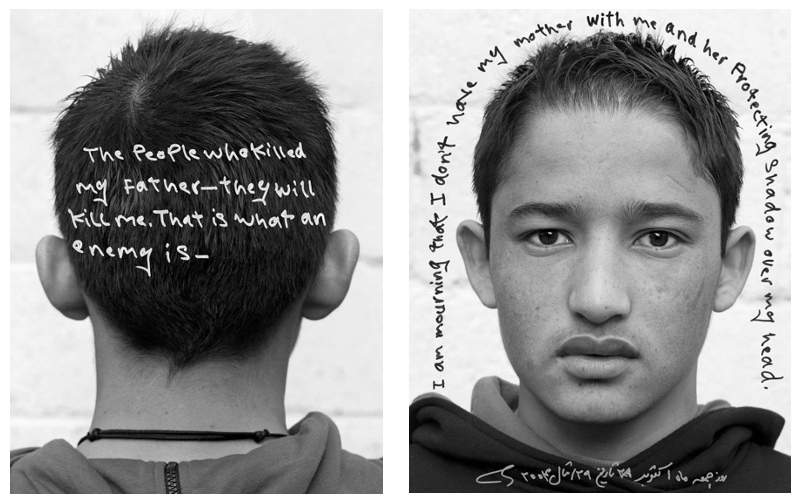

Dion exemplifies the manner in which such questions can be approached through art practice. My particular interest in Dion’s work here is the way in which he succeeds, in the installations that result from his work, in creating a relatively open text. My first encounter with his work, and a project that relates most closely to my current work around the River Roding in east London, was Tate Thames Dig (1999). The work, which was commissioned for the opening of the Tate Modern, was created through three distinct phases of activity: the dig, the cleaning and classification of artefacts, and their formal presentation. The dig involved 25 volunteers from the areas around the Tate galleries in London in collecting objects (whatever took their interest) from the banks of the Thames in the Bankside and Millbank areas. These objects were then publicly cleaned and classified by the volunteers (Figure 2), according to a typology based on formal resemblance (for instance, according to material).

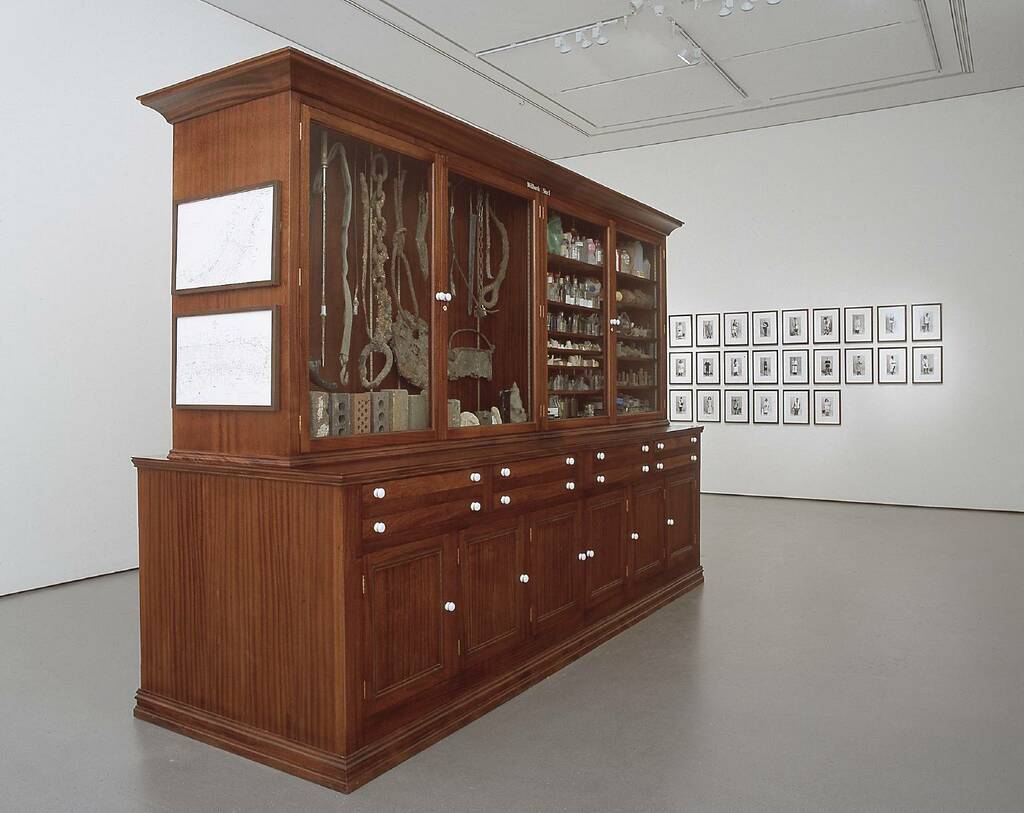

Finally, the artefacts were displayed in the gallery in a large cabinet (Figure 3), without any text or labeling. Visitors were able to open the drawers of the cabinet and explore the contents. Other items were displayed alongside the cabinet, including some of the tools used and texts on archaeology and critical theory, portraits of participants and a video documenting the dig and cleaning/classification process with testimonies from Dion and volunteers.

The volunteers were either over 65 or under 17. According to Blazwick (2001) ‘working with seniors Dion discovered amateur historians and botanists while the diverse group of disenfranchised kids produced budding archaeologists and poets’ (p.108). The process builds on Dion’s own research into archaeological method, including the seeking of permissions for the dig, and reference to prior work by social historians, thus offering a form of aesthetic practice that lies alongside and supplements the institutional and formal aspirations of production of archaeological knowledge.

Claims have been made for the democratic nature of the process and the way mundane objects are given value in the gallery setting. Bourriaud (2002), for example, presents Dion’s work as an exemplification of a democratising ‘relational aesthetics’, that is art that is produced using procedures drawn from other disciplines, and thus bringing to the fore the relational basis of disciplinary knowledge. Ross (2006), however, points out that throughout the process Dion is clearly in charge and that ultimately aesthetic concerns take precedence over all others. This aspect of Ross’s critique bears resemblance to Bishop’s (2012) criticism of participatory art more generally as merely creating a context for the artist’s creation of aesthetic objects (a critique which specifically targets Ewald’s work amongst others). Ross also observes that the approach taken in Dion’s archaeological projects is not interdisciplinary, in the sense of disciplines working together on a shared project from distinct disciplinary perspectives. Rather art and archaeology operate in parallel with each other, and through the mimicry of scientific processes Dion makes alternative epistemological claims. As Ross states:

‘One of the surprises of Dion’s body of work is that it suggests that art may just as well involve epistemological research and study as the human or natural sciences’ (p.179).

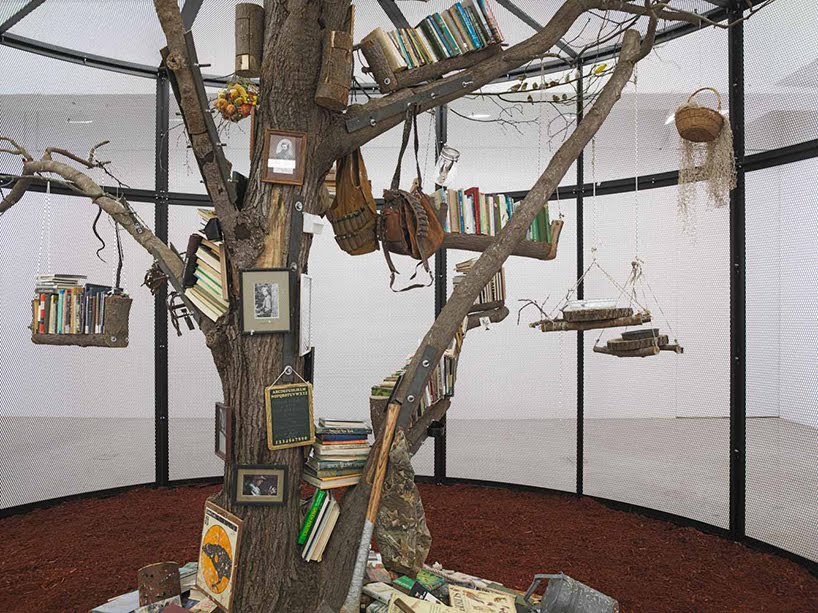

The particular interest for me is the way the material collected is presented to viewers/users who are able to produce their own narratives and accounts from the material. In other projects, such as The Library for the Birds of New York/The Library for the Birds of Massachusetts (2016/7: see Figure 4) and Rescue Archaeology (2005), Dion extends the scope and form of the material presented (including artefacts made specifically for the installation, books, plant material, bugs and living birds) and enlarges the performative aspects of the work and opportunities for viewers to actively engage in the production of new knowledge.

The work acts to engage and provoke, rather than (merely) represent or present a narrative. Like Laurence, Dion brings nature inside the gallery in challenging and engaging ways, in a form of ‘geoaesthetics’ (Cheetham, 2018, p.123) which explores the intersection of speculations from a range of disciplines on the relationship between the human and the more-than human with art practices. As Marsh (2009) observes Dion ‘has created an expansive body of work that investigates how cultural institutions shape our understanding of the natural and built environments through the classification and display of artifacts’ (p.33).

References

Bishop, C. (2012) ‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents’ in Bishop, C. (ed.) Artificial hells: participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. London: Verso, pp. 11–40.

Blazwick, I. (2001). Mark Dion’s “Tate Thames Dig.” 24(2), pp. 105–112.

Bourriaud, N. (2002) Relational Aesthetics (trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods), Paris: Les Presses du Reel.

Cheetham, M. A. (2020) Landscape into Eco Art: Articulations of Nature Since the 60s, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press.

Dion, M. (2013) ‘Contemporary Cabinets of Curiosity: Artist Mark Dion’. Presentation at the Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas. 27th January 2013. Online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FnH3UocF2Sk&feature=emb_rel_end [accessed 10.11.20]

Foucault, M. (1966) The Order of Things: An archaeology of the human sciences. Translated from French. London: Tavistock, 1970.

Foucault, M. (1969) The Archaeology of Knowledge. Trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith. London: Routledge, 2002.

Marsh, J. (2009) ‘Fieldwork : A Conversation with Mark Dion’, American Art, 23(2), pp. 32–53.

Ross, T. (2006) ‘Aesthetic autonomy and interdisciplinarity: A response to Nicolas Bourriaud’s “relational aesthetics”’, Journal of Visual Art Practice, 5(3), pp. 167–181.

Talasek, J. D. (2014) ‘Mark Dion: An Archaeology of Knowledge’, Issues in Science and Technology, 31(1), pp. 7–13.