Art theorist Stephen Wright (2014) argues that, over a period of several decades, there has been a what he calls a ‘usological’ turn across all sectors of society. Networked culture, alongside a broader social, cultural and economic turn away from exceptionalism and professional expertise, has placed users in a key role in the production of knowledge, meaning and value which challenges established distinctions between consumption and production. In the arts this move to a more inclusive ‘usership’ has placed the ability of practitioners to offer an array of artistic competences for use in a range of contexts above the aesthetic function of art. In this way, artists offer particular resources and perspectives in collaborative settings. Art in this sense is a distinct form of practice but not exceptional. This perspective resonates with the manner in which my own practice has developed, with an emphasis on creating work together with and alongside others. In developing a lexicon of usership, in which he elaborates emergent concepts and identifies institutions in decline, Wright describes several modes of usership, including hacking, gaming, gleaning, poaching, piggybacking and, central to the direction I am taking in the development of my projects, ‘use it together’ (UIT), a hands-on social and inclusive development of ‘do it yourself’ culture.

The development of an approach to art practice that emphasises collaboration and mutual learning is exemplified by photographer Wendy Ewald, who for over forty years has been working collaboratively with communities, in particular with children, women and families, in using photography in the exploration of their own lives and aspirations. Her work addresses identity and cultural difference and raises fundamental questions about authorship and the power and identity of the artist. Amongst artists adopting a participatory form of practice, Ewald is notable in placing a strong emphasis on learning in her projects and interventions (Figure 1).

As Azoulay (2016) observes, a concern for the learning process is at the heart of all Ewald’s work and that in many of her projects ‘she teaches photographic literacy while learning what photography can be for those that she teaches’ (p.190). Ewald (2015) gives an illuminating account of how she worked with participants in her This is Where I Live (2010-13) project in Israel and the West Bank (Figure 2), including discussion of the work of other photographers, technical instruction, strategies for selecting what photographs to take and how to discuss images together.

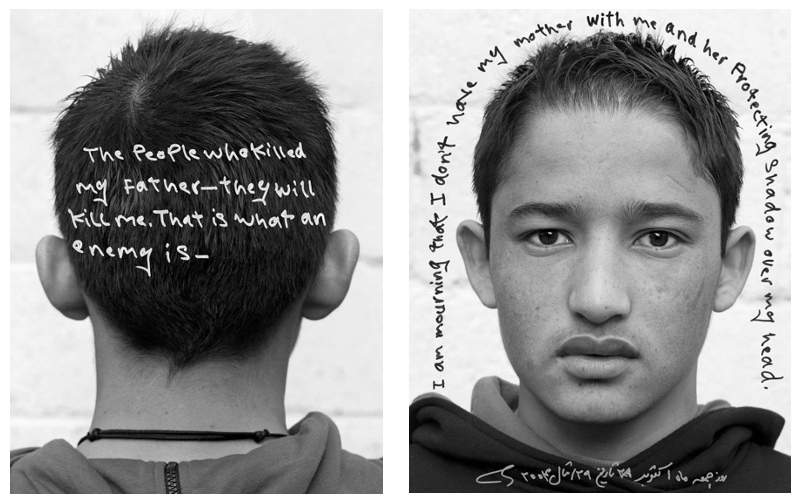

In Towards a Promised Land (2003-6) Ewald collaborated with children who had come to Margate, on the Kent coast, either alone or with their families to make a ‘fresh start’. This included children who had migrated to the UK and been resettled in Margate. Many had suffered from the trauma of family upheaval, and those seeking asylum, for instance from the Middle East and Africa, who, facing an uncertain and precarious future, were placed in temporary hotel accommodation in the town. Ewald worked with 20 children, photographing them and their possessions, and teaching them to take photographs and record their stories.

As with earlier work (such as In Peace and Harmony: Carver Portraits, 2005, in Richmond, Virginia), children were asked to write on pictures of their faces and the back of their heads (Figure 3), which were juxtaposed with photographs of everyday objects selected by the children to create 3m by 4m triptychs printed on vinyl and mounted on the cliff faces looking out to sea. Later, following discussion with members of the community, banners made from the work were displayed in prominent public places around the town (Figure 4 and 11).

As Hyde (2005) notes ‘By presenting the work within the public spaces of her collaborators’ lives instead of within the more exclusive halls of a museum or gallery, Ewald expands and diversifies her audience and creates the potential for meaningful public dialogue’ (p.189). The use of public space in this way transforms the urban landscape and the experience of members of the community as they move through it.

It is difficult to judge the impact of this work on the individual participants and the wider community. Some insight is provided by the 2020 edition of Portraits and Dreams for which Ewald returns to the county in Kentucky where she worked with children in the 1970s. The reflections of the participants are captured in a documentary film and book (Ewald, 2020), and a joint exhibition created with one of the participants who subsequently became a wedding photographer (Figure 5).

Katherine Hyde (2005) analyses Ewald’s work from the perspective of visual sociology, illustrating how this form of work can contribute to our understanding of social class, race and gender in the (re)production of social inequality, and the part played by visual culture in these processes. In considering Ewald’s 2005 American Alphabets series (Figure 13), Hyde raises an issue that is central to all forms of art that attempt to develop and convey a narrative, or ‘tell a story’.

As with Ewald’s entire body of work, it is interesting to consider here whether and how the portraits expand our knowledge. Does the White Girls alphabet present a challenge to what we know? Does it perpetuate stereotypes? It is worth reflecting on the cultural assumptions and implications tied up in our immediate, visceral response to these images and words. (p.179)

Esther Allen (2016), in an interview with Ewald, notes that her work is frequently cited by psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, historians and educators, but rarely, and notably for a fine art photographer, by art historians. Ewald suggests that this is because she attributes the photographs to the participants, challenging dominant practice in the arts. She clearly does, though, consider herself to be primarily a fine art photographer. There is little attention in her work to issues of pedagogy nor to other disciplines. Ewald’s work thus acts as a resource for those working in and across other disciplines but cannot be considered interdisciplinary in itself. Katzew (2003), in a review of Ewald’s (2001) book I Wanna Take Me a Picture: Teaching Photography and Writing to Children raises a number of critical issues about both the selection of communities and ways of working with participants from a sociological and educational perspective, issues that remain implicit in Ewald’s work.

References

Allen, E. (2016) ‘Wendy Ewald’, Bomb, (135), pp. 113–123.

Azoulay, A. (2016) ‘Photography consists of collaboration: Susan Meiselas, Wendy Ewald, and Ariella Azoulay’, Camera Obscura, 31(1), pp. 187–201.

Ewald, W. (2003-6) Towards a Promised Land. Online at http://wendyewald.com/portfolio/margate-towards-a-promised-land/ [accessed 10.11.20].

Ewald, W. (2015) ‘This Is Where We Live’, Financial Times, 2 January, pp. 4–7.

Ewald, W. (2020) Portraits and Dreams, Photographs and Stories by Children of the Appalachians, updated and expanded edition, London: MACK.

Hyde, K. (2005) ‘Portraits and collaborations: A reflection on the work of Wendy Ewald’, Visual Studies, 20(2), pp. 172–190.

Katzew, A. (2003) ‘I Wanna Take Me a Picture: Teaching Photography and Writing to Children’, Harvard Educational Review, 73(3), pp. 466–475.

Wright, S. (2014) Toward a Lexicon of Usership. Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum. Online at https://www.arte-util.org/tools/lexicon/ [accessed 10.11.20].