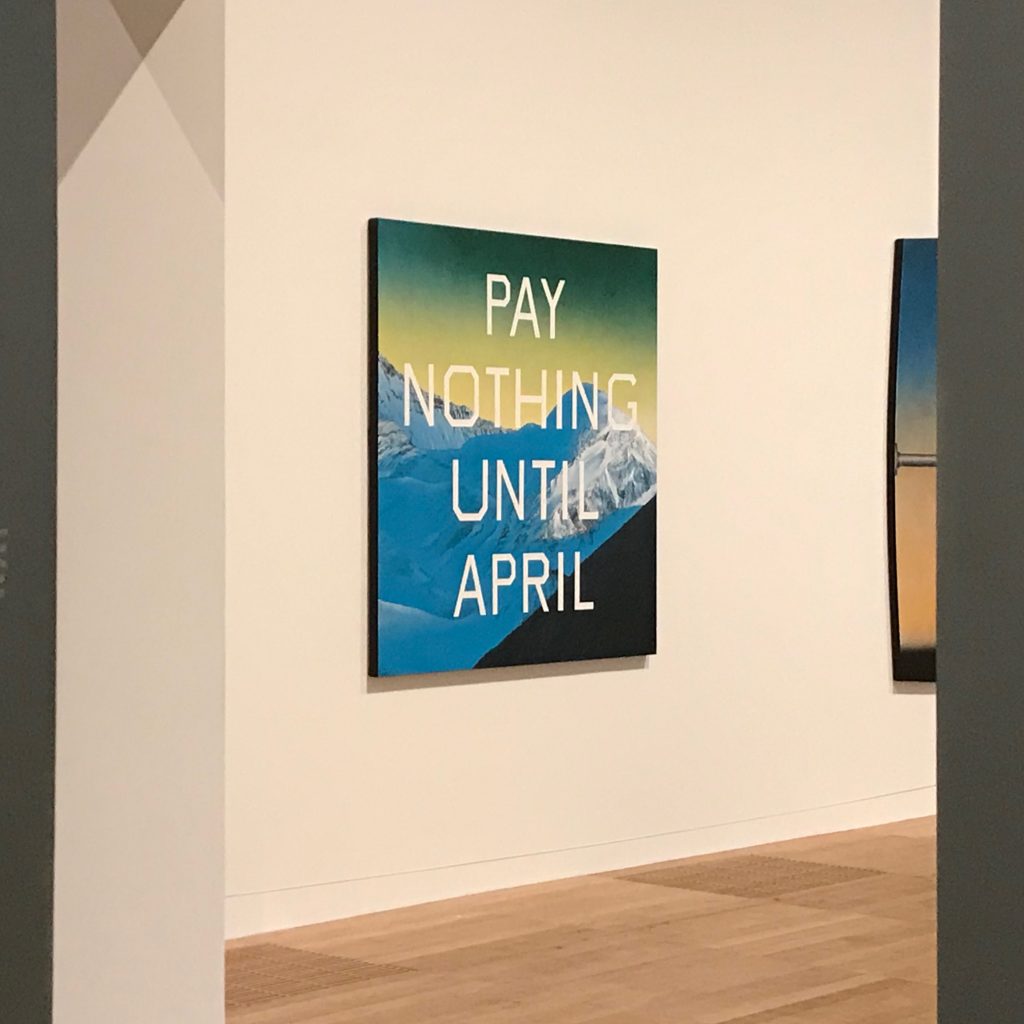

Over the next few months I want to consider different commercial models (and in particular, how these might relate to community art, and alternative ways of funding this type of work). Warhol plays a key part in defining the limits in the production of marketable original art, building on Duchamp’s questioning of the need for the artist to be the ‘maker’. The separation of the artist from the market (value) is neatly explored in Nathaniel Kahn’s 2018 film The Price of Everything. Collector Stefan Edlis reflects on the absence of work by Jeff Koons (a key contemporary exponent of the ‘factory’ mode of art production) in the 2016 auctions, noting that “the real estate people started thinking of Jeff Koons as lobby art”, to which Sotheby’s executive vice president Amy Cappellazzo adds “The kiss of death. You never get out of the lobby once you’re in there.” The trajectory of Larry Poon’s is presented as a counter example, having drifted into obscurity by turning away from the initial commercial success of his 1960s ‘op-art’ dot paintings to pursue his own artistic interests, to be ‘rediscovered’ by the galleries in later life. Poons ceases to produce the dot paintings before market desire is fully developed (so achieves rarity but before securing sufficient market prominence).

This resonates with the painful trajectory of Richard Hambleton, as portrayed in Oren Jacoby’s 2017 film Shadowman, who came to prominence as a street artist, around the same time as Basquiat and Haring (though he appears to have been significantly more conceptually sophisticated, and diverse in terms of artistic practice, than his renowned street art contemporaries). Hambleton’s use of drugs and chaotic lifestyle, and latterly skin cancer, appear to have thwarted a more conventional ‘art-life’, exacerbated by a change in direction (from street art to landscapes) at the point at which his work was reaching a critical stage in terms of recognition, mirroring Poons. Like Poons, he has also continuously produced work motivated by his own artistic interests and drives (frequently against the grain of the prevailing market), and was subject to a number of ‘re-discoveries’ by collectors (with the attendant exploitation, often, in Hambleton’s case, in the form of accommodation, food and/or a studio in exchange for new works, and entailing in some cases intimidation from so called ‘benefactors’). The prolific, and extended, production of new work, of course, undermines rarity and thus effects market value. Basquiat’s biographer, Phoebe Hoban, states ‘both Basquiat and Haring, without meaning to sound as cynical as this sounds, they made a very good career move; they died’. Chillingly, Hambleton, reflecting on the rise and demise of Basquiat and Haring, presents his own trajectory as a form of living death (“At least Basquiat, you know, died. I was alive when I died, you know. That’s the problem.”).

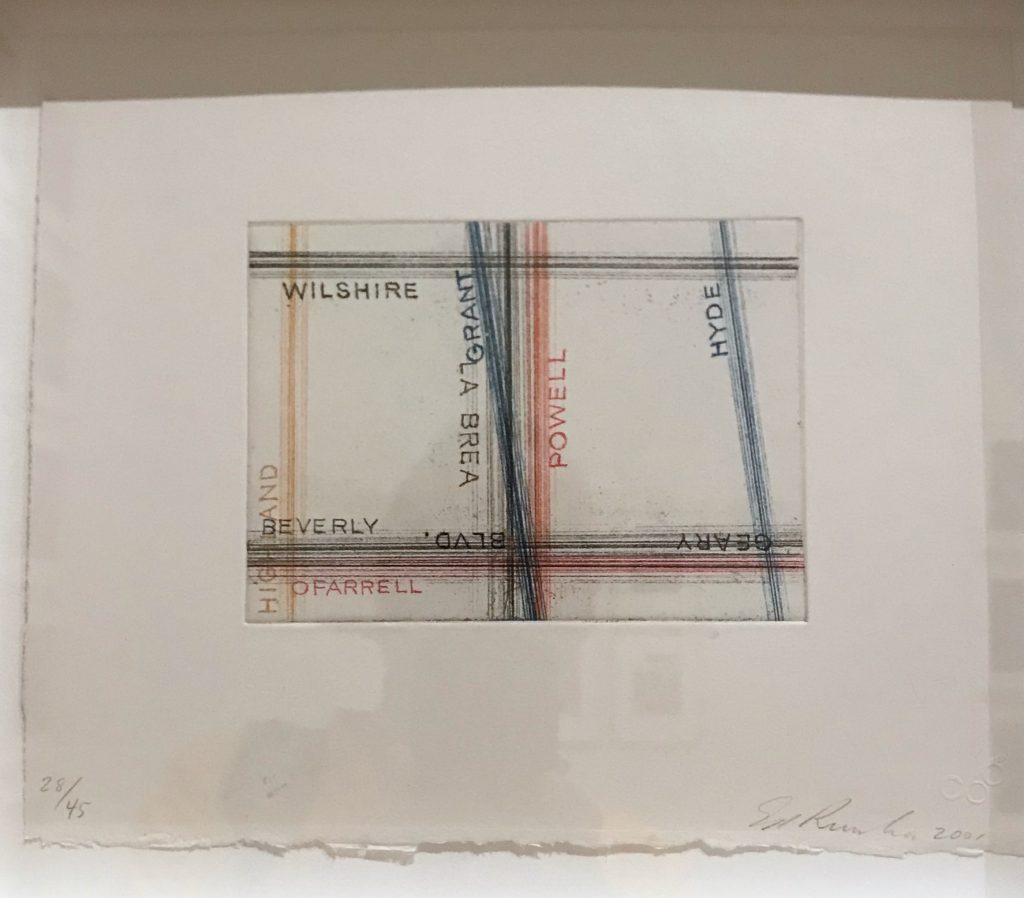

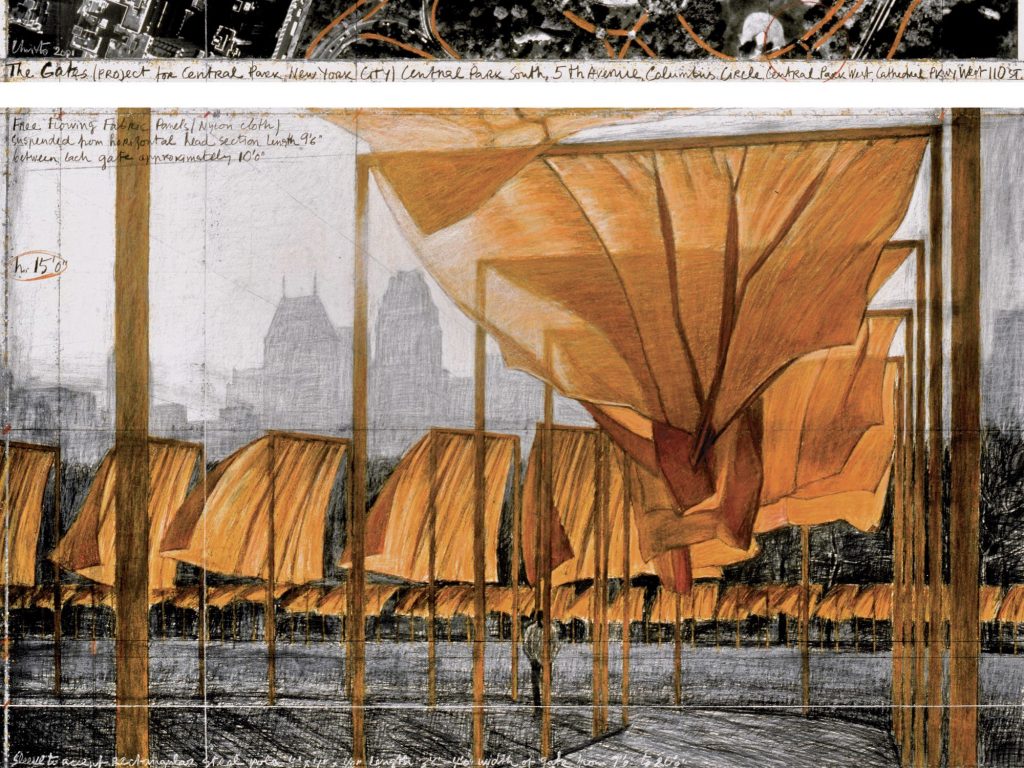

Christo and Jean Claude exemplified an alternative approach. No public funding was received for any of their large scale public art works, for which the legal costs alone amounted to tens of millions of dollars in some cases. Funding was raised through the sale of Christo’s preliminary drawings and other visual work relating to the development of the pieces. The rarity of the work is ensured by the limited volume and time frame in the preliminary, planning and realization stages of the work. The desirability, for collectors, is enhanced by the impact and public profile of the public works. Whilst this is only a viable strategy for artists of substantial standing, producing my own work alongside participants and selling this would be one way of funding community-focused art projects (taking care to put all proceeds back in the community, and to be fully transparent in this use of income from this work). Though not a dominant issue for me, I’ll come back to funding and commercial issues when I post about the 15th August online workshop with Lewis Bush, and to consider again the idea of hidden labour in artistic production.

[Whilst putting together a piece for the DFA programme, I have come across other posts from the MA that address this issue, for instance this reflection from the first module. This raises the question of how best to draw on this material in working towards the doctorate, and whether some work needs to be done to draw out key themes and provide links to where they are discussed].