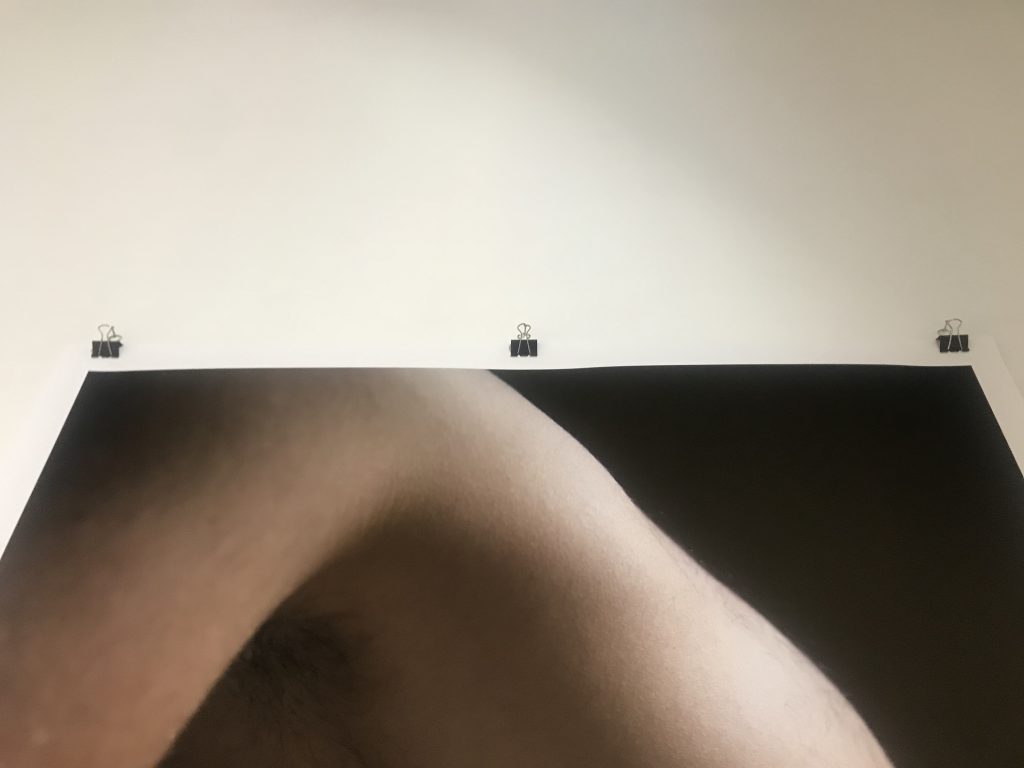

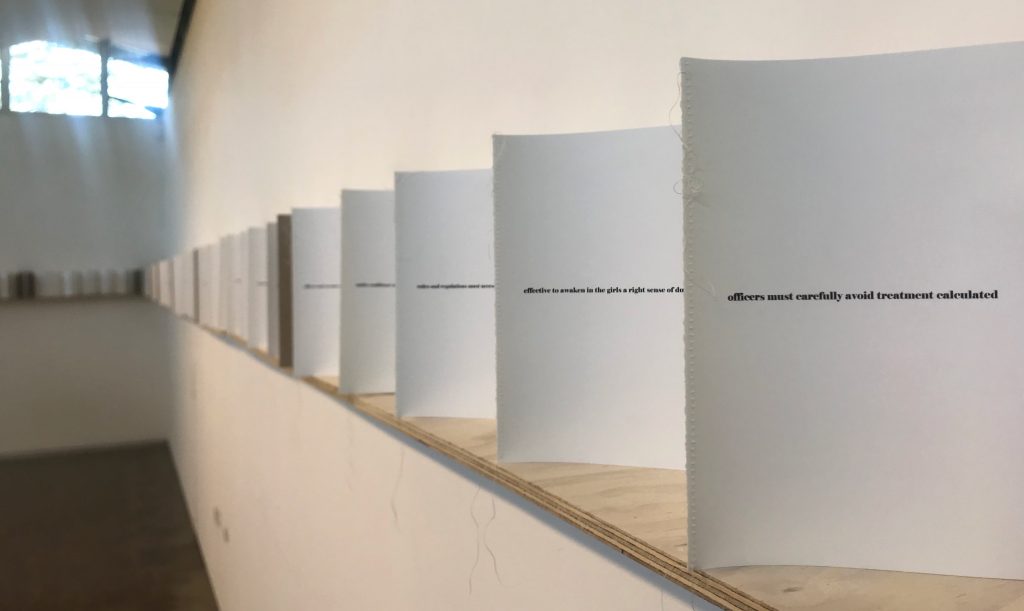

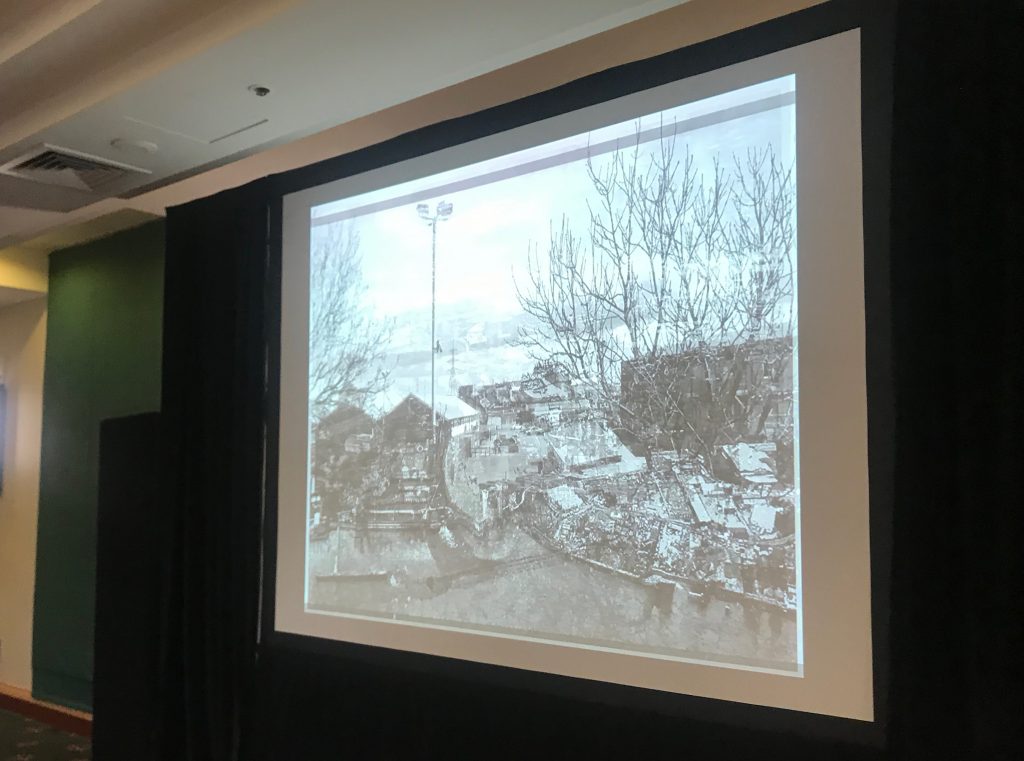

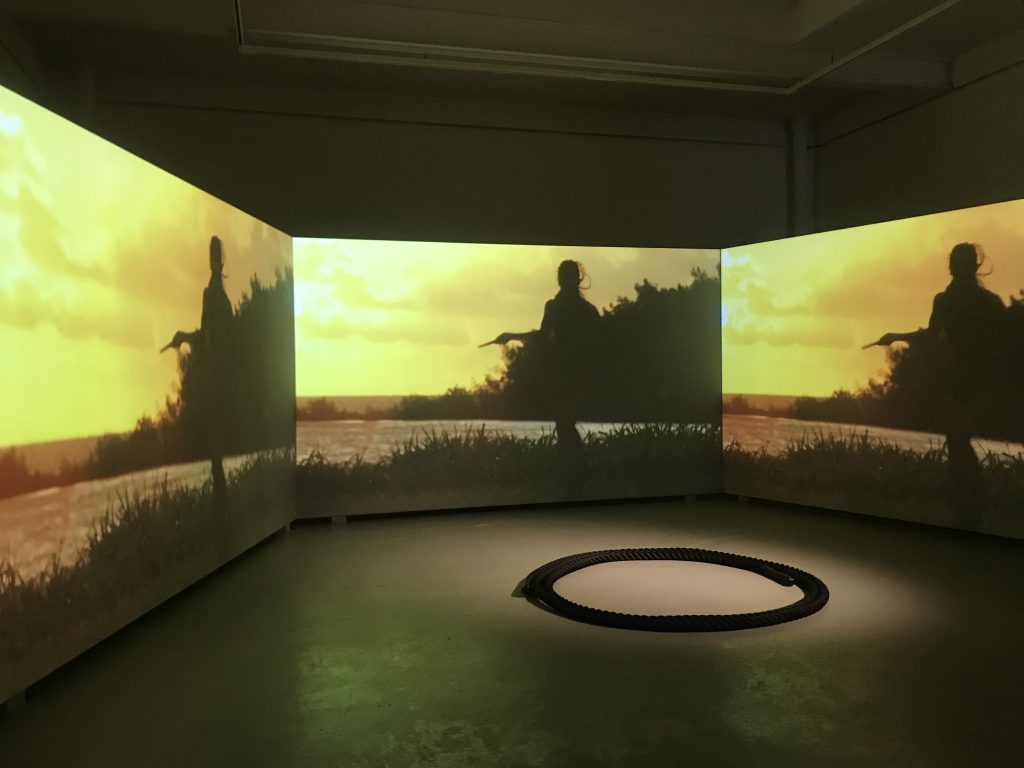

My project involves the exploration of resident engagement with urban regeneration in east London. I have continued to work broadly along the lines set out in my project proposal. The work includes three levels of image making: (i) images made by residents as part of a process of understanding the experiences, lifeworlds and aspirations of individuals and communities; (ii) collaborative image making with community and activist groups for advocacy; (iii) my own artistic response to the changes that are taking place and the ways in which communities are affected by urban regeneration. Over the previous three modules I have developed close working relationships with a number of groups and have focused my work on a particular part of east London (Barking and Dagenham, though I have retained strong links with groups on and around the Olympic Park). I have strengthened the conceptual basis for my work and have developed my visual strategy and methodology in line with this. My current work can be seen here. I have posted regular updates on the development of my project in my CRJ (for instance, here). Most recently, my work has started to address environmental and ecological issues more directly, and I have begun to engage with different conceptions of time (both in response to developments in theoretical physics, and in order to move away from anthropocentric forms of understanding). I have also attempted to bring the work together with other work I have been doing on object oriented learning and indigenous forms of knowledge. I have attempted to assess how the development of my ideas and practice over the previous module relates to the learning objectives for the programme here.

According to the programme description, by the end of the module we should demonstrate: ‘an increased understanding of how complex and sophisticated image-making practices and visual communication strategies can be incorporated into your own practice’. I just want to unpack this a little to map out what I want to achieve over the course of the module, particularly given that this is the last taught component before the FMP.

In my research proposal I identified the following skills for development in this module:

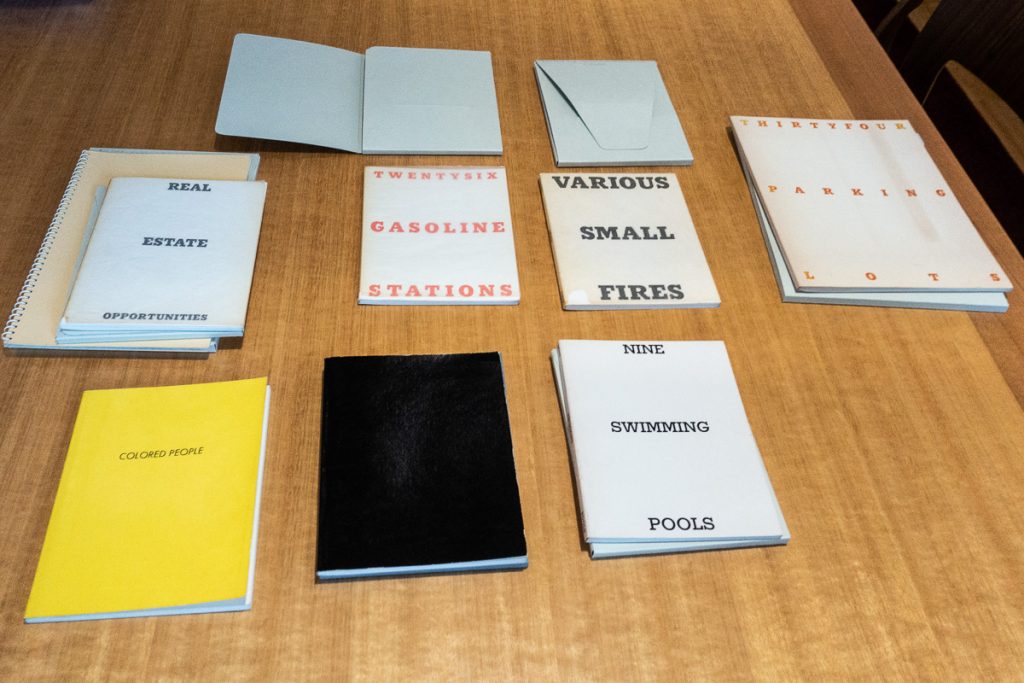

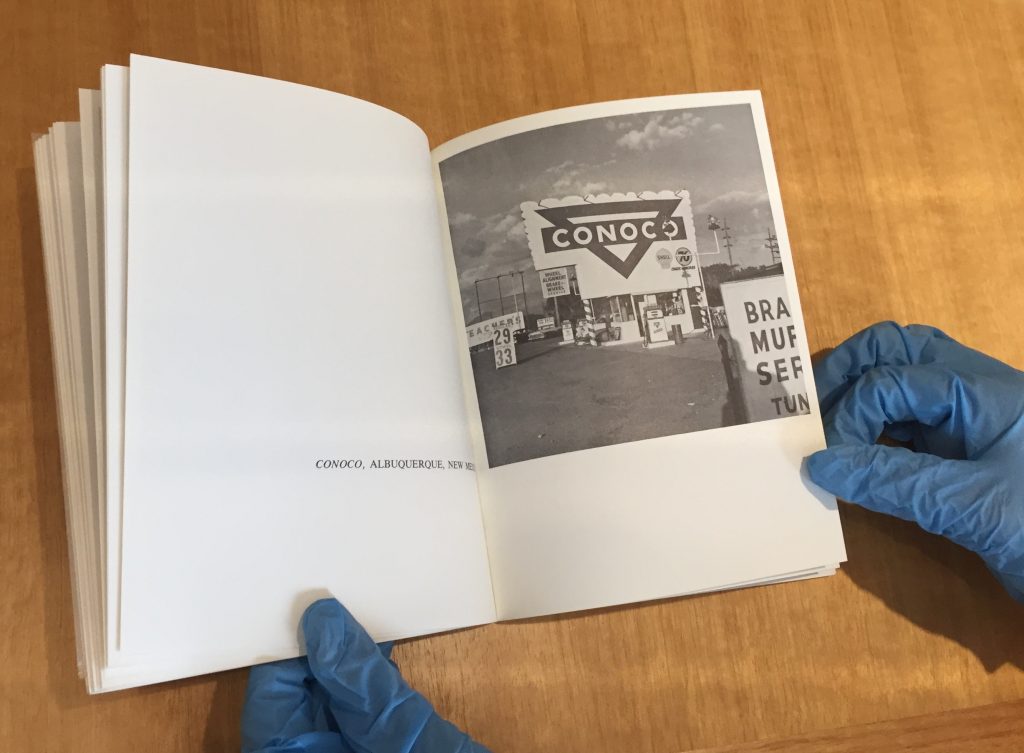

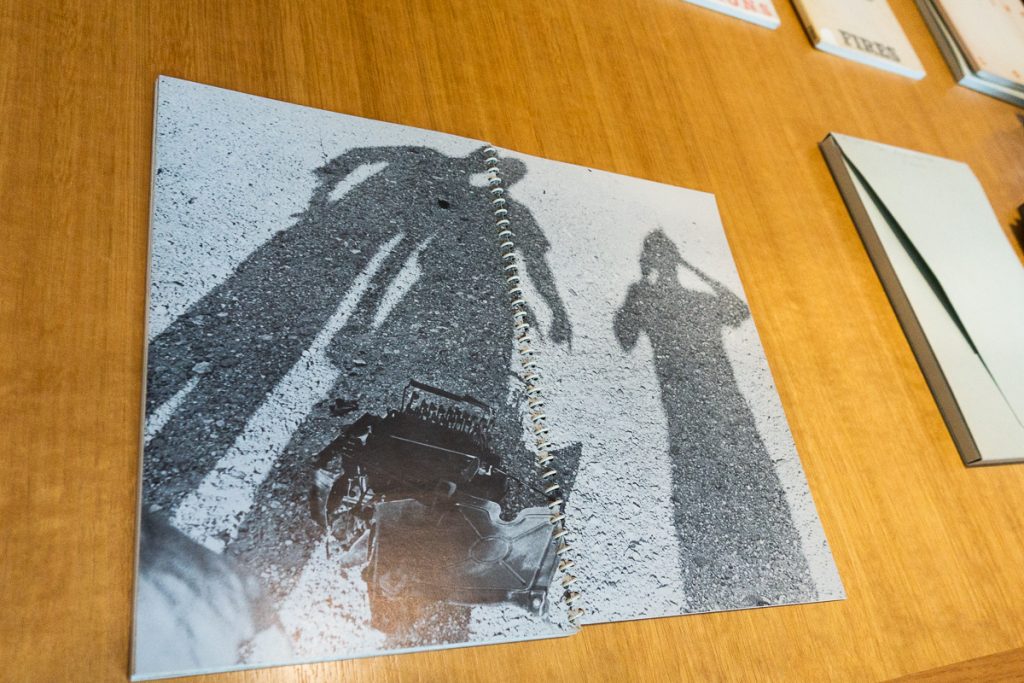

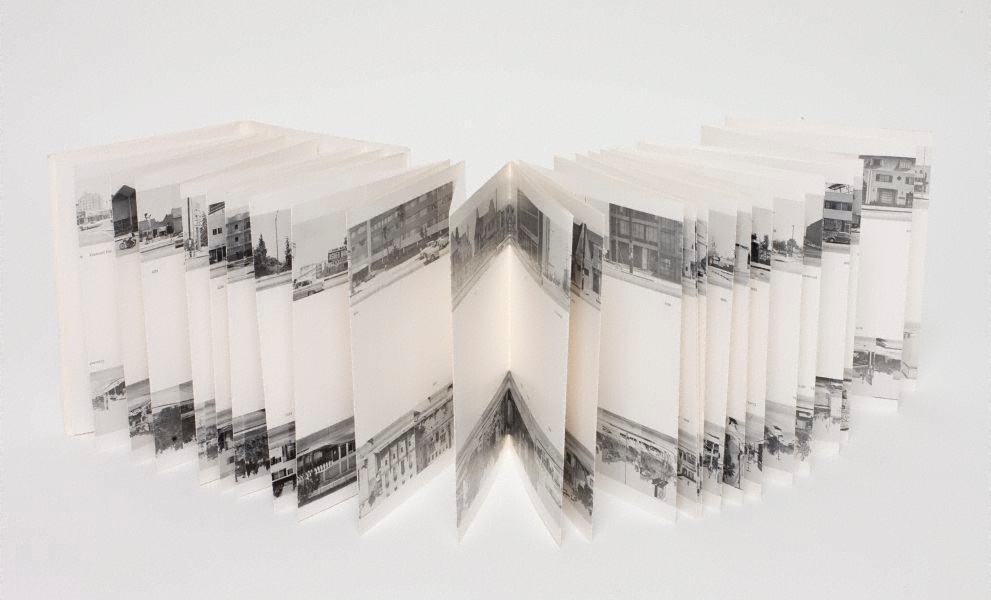

Photo-book production, installation design, printing for exhibition and alternative modes of presentation to different audiences, physically and online.

In relation to the schedule for completion of the project, I earmarked the following actions for this module:

Continuing personal photographic work and collaborative image making. Explore alternative means of presenting images (including books, installations and online galleries). Conduct workshops to prepare community members for Photovoice work. Determine form of personal and collaborative image making, and process of dissemination. Start collection of Photovoice data.

In the light of the ways in which my work has developed over the past year, modifying and expanding the above, this is what I want to achieve over the coming three months:

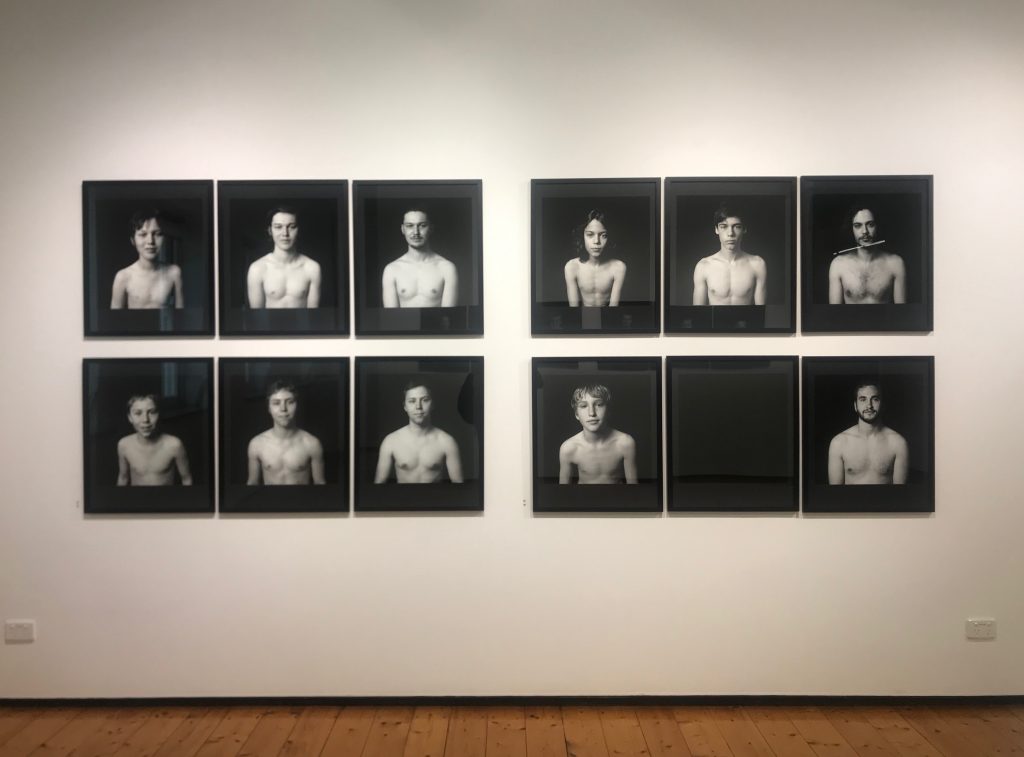

- Refine ways of working with participant images and image making. While in Newcastle, I will spend some time working with two projects in the Centre that are using Photovoice (Wang & Burris, 1997) styles of work and arts-based methods of enquiry (with victims of domestic violence and with young offenders in rural areas). Working from the critical work of Sinha & Back (2014), I want to refine the approach to bring it conceptually closer to other strands of my work. Within the module, there are questions about how (if at all) this work is presented to an audience, and ethical issues around working with images made by others for different purposes to be addressed.

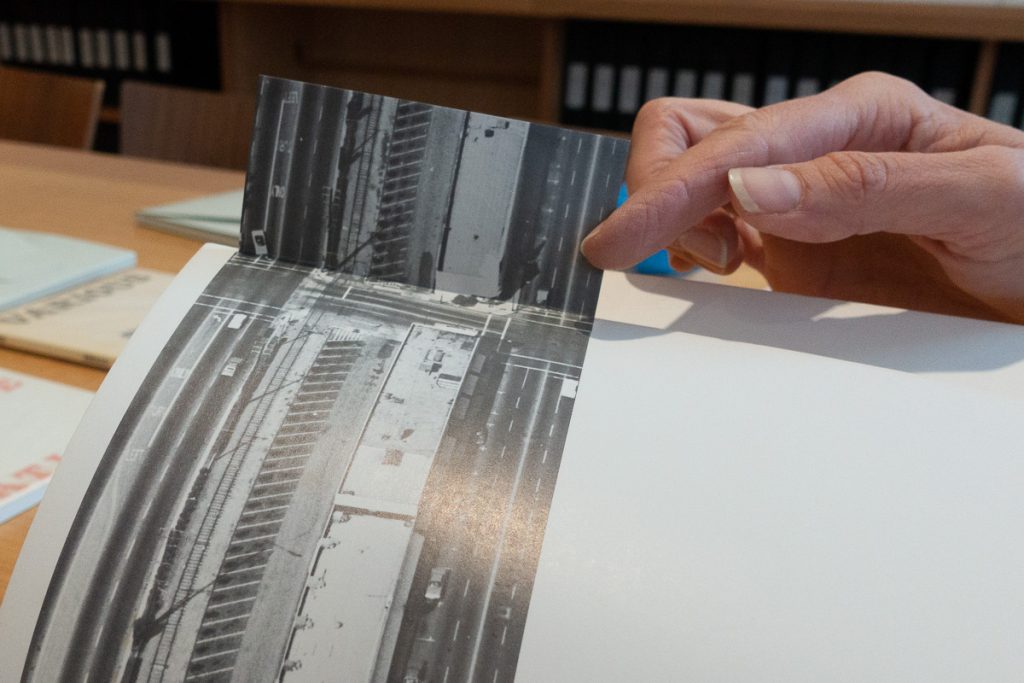

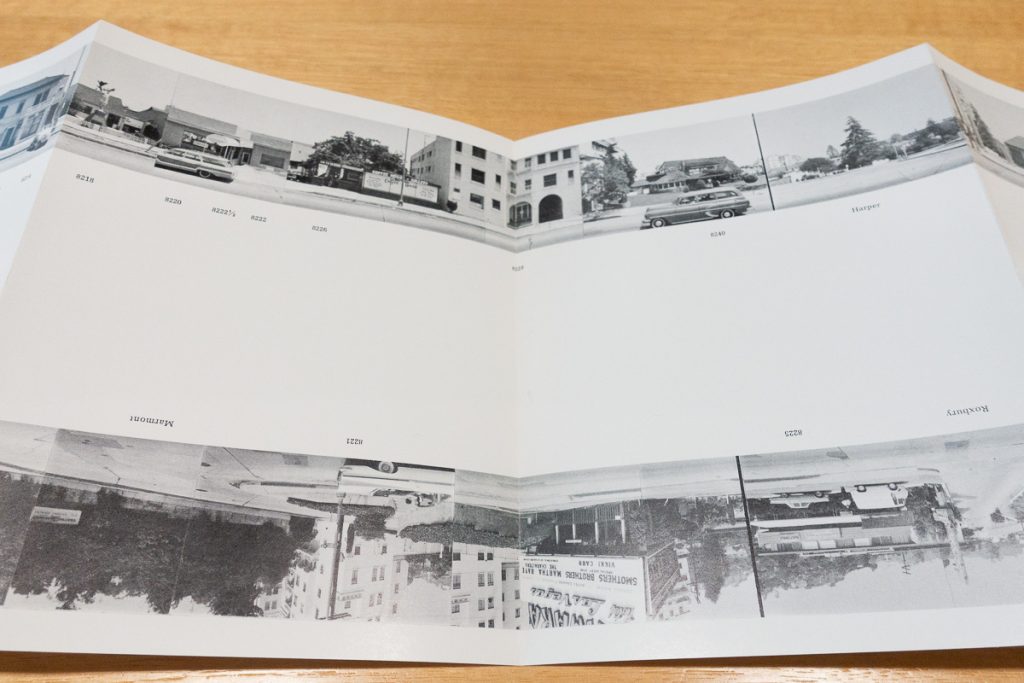

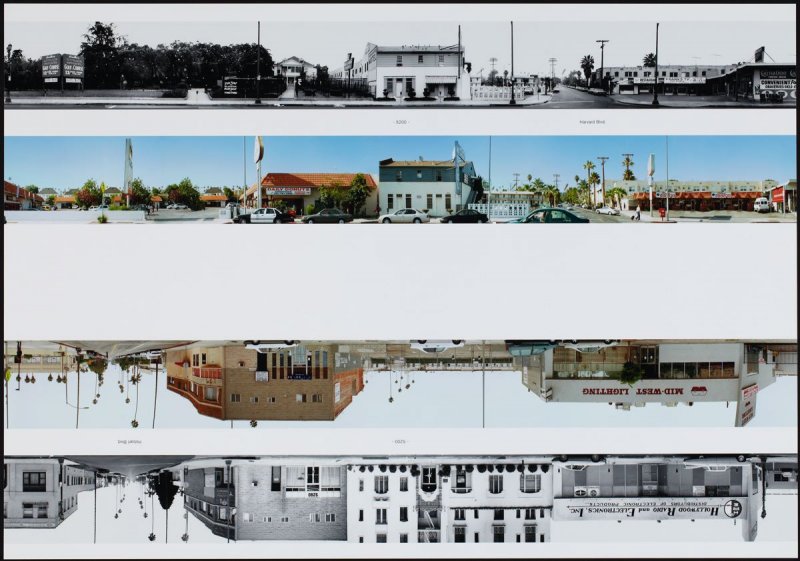

- Incorporate archival images into my work. I have started to do this with the erase series (which incorporates a montage made of archival images of the Creekmouth estate). I need to do some work in the Valence House archives, and also think about how to use the Courtauld archive.

- Develop the repository of images for advocacy with the Thames Ward Community Project and the Barking and Dagenham Heritage Conservation Group. I want to address the issue of how these relate to other aspects of my work, and the extent to which, for instance, they could together be considered as some kind of archive, and if so, what form might this archive take.

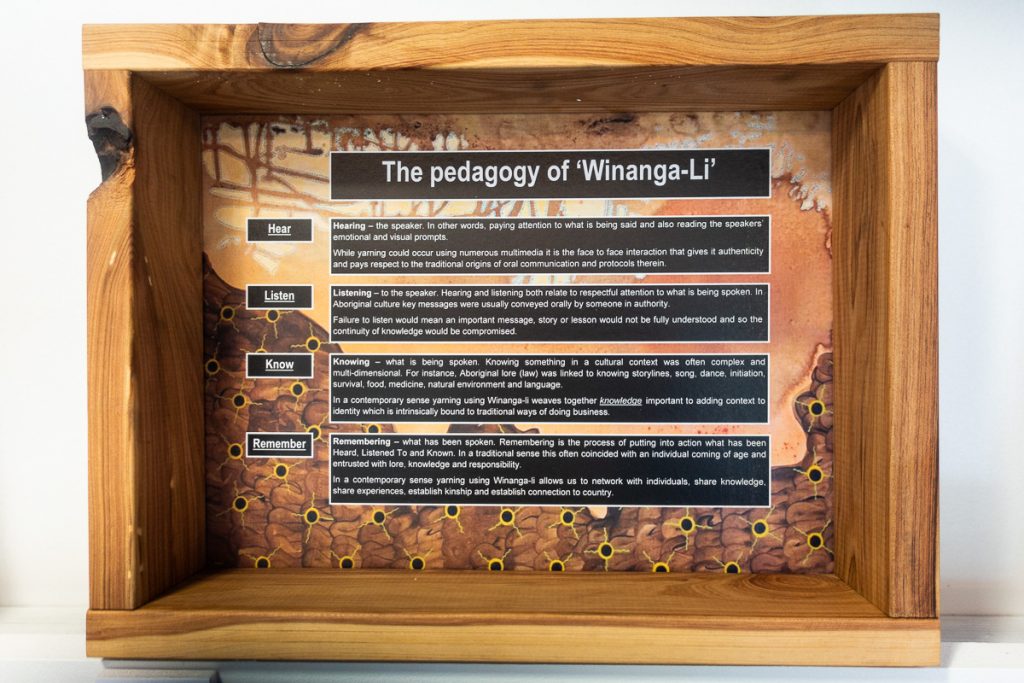

- Consolidate the conceptual strands from Informing Contexts and focus these on the development of a coherent and informed methodology (with associated strategies and tactics). Lemke’s (2017, 2015) advocacy for a form of relational post-humanism holds some potential in bringing together linguistically inflected post-structuralism with more recent post-humanist and new materialist theory (see, for instance: Barad, 2007 & 2008; Coole & Frost, 2010). Likewise, the engagement by Fitzgerald et al (2018 & 2016) of neuroscience and biology with sociology in understanding contemporary urban life facilitates incorporation of objects and the environment with exploration of the human impact of urban development. The third dimension of this is dialogue with indigenous people’s notions of relationship of the body to the land (and experience of displacement), and running through this the role of objects, materials and making in fostering understanding.

- Explore the relationship between the digital and the analogue. In the work produced during the last module, I established a resonance between the move from analogue images to digital composites (and animations) and the rendering of residents and communities as data in the shaping of local housing development and planning initiatives. This needs to be further developed both in terms of a visual strategy and conceptually, bearing in mind, for instance, Goriunova’s (2019) notion of the digital subject.

- Determine the focus for the final major project (from amongst the settings and themes of my work to date) and the form in which the outcomes will be presented.

References

Barad K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham/London: Duke University Press.

Barad K. 2008. Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. In Alaimo S and Hekman S (eds) Material Feminisms. Bloomington/Indianapolis: Indiana University Press: 120–154.

Coole D. and Frost S. (eds). 2010. New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Durham/London: Duke University Press.

Fitzgerald, D., Rose, N. and Singh, I. 2018. ‘Living Well in the Neuropolis’, The Sociological Review, 64: 221–237.

Fitzgerald, D., Rose, N. and Singh, I. 2016. ‘Revitalizing sociology: Urban life and mental illness between history and the present’, British Journal of Sociology, 67(1): 138–160.

Goriunova, O. 2019. ‘The Digital Subject: People as Data as Persons’, Theory, Culture and Society. doi: 10.1177/0263276419840409.

Lemke, T. 2017. ‘Materialism without matter: the recurrence of subjectivism in object-oriented ontology’, Distinktion, 18(2): 133–152.

Lemke, T. 2015. ‘New Materialisms: Foucault and the “Government of Things”’, Theory, Culture & Society, 32(4): 3–25.

Sinha, S. and Back, L. 2014. ‘Making methods sociable: Dialogue, ethics and authorship in qualitative research’, Qualitative Research, 14(4): 473–487.

Wang, C. and Burris, M. A. 1997. ‘Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment’, Health Education & Behavior, 24(3): 369–387.