Simon Munro, Yearning to Yarn: The Artefact in Research, The University Gallery, University of Newcastle, NSW. Workshop: 14th May 2019.

This exhibition is the culmination of a research project at the University of Newcastle Department of Rural Health in Tamworth, NSW. The project explores the ways in which aboriginal ways of knowing can be used to support the clinical placement experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health professional students. The project was part of one of the research programmes funded and supported by the Centre for Excellence in Equity in Higher Education, in which I work. My role has been to run workshops on research design, methodology and methods, and on academic writing and publication, and to advise and mentor grant holders. In this CRJ post, I am going to focus specifically on the arts-based methodology used in this project, on the exhibition and associated workshop and on the more general issue of the significance and use of artefacts in enhancing our understanding. The work also raises questions about how we understand our relationship to the land and the environment (a key component of Australian aboriginal culture). These are all issues at the heart of the development of my photographic practice. The exhibition, and reflection on the process developed by Simon and the project team, provide an apposite opportunity to gather together thoughts and relate these to the development of my FMP and my photographic practice more generally.

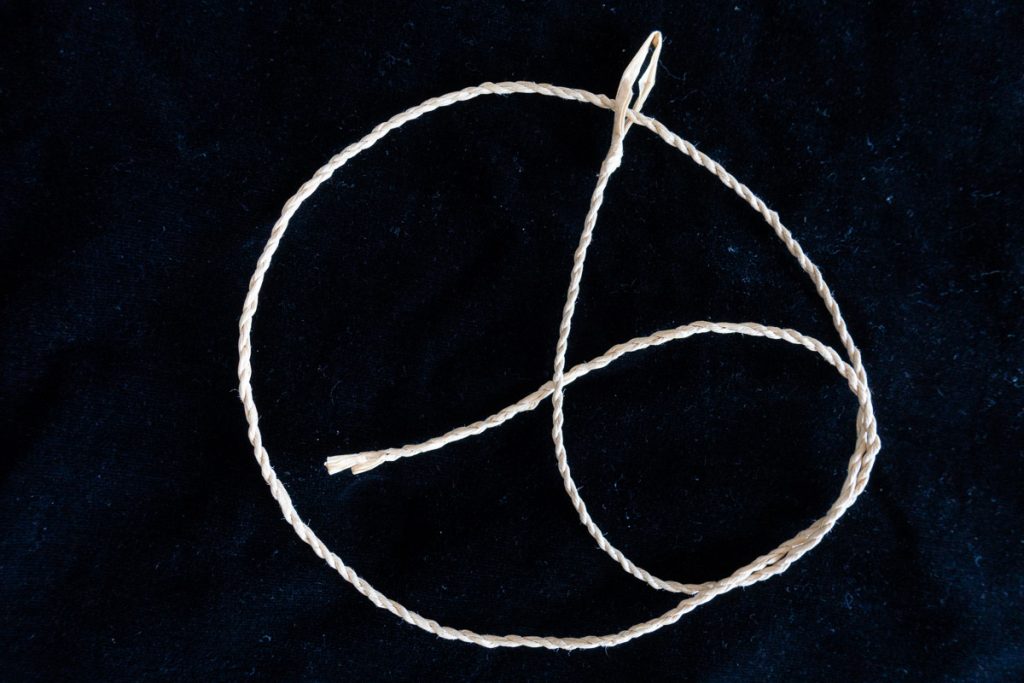

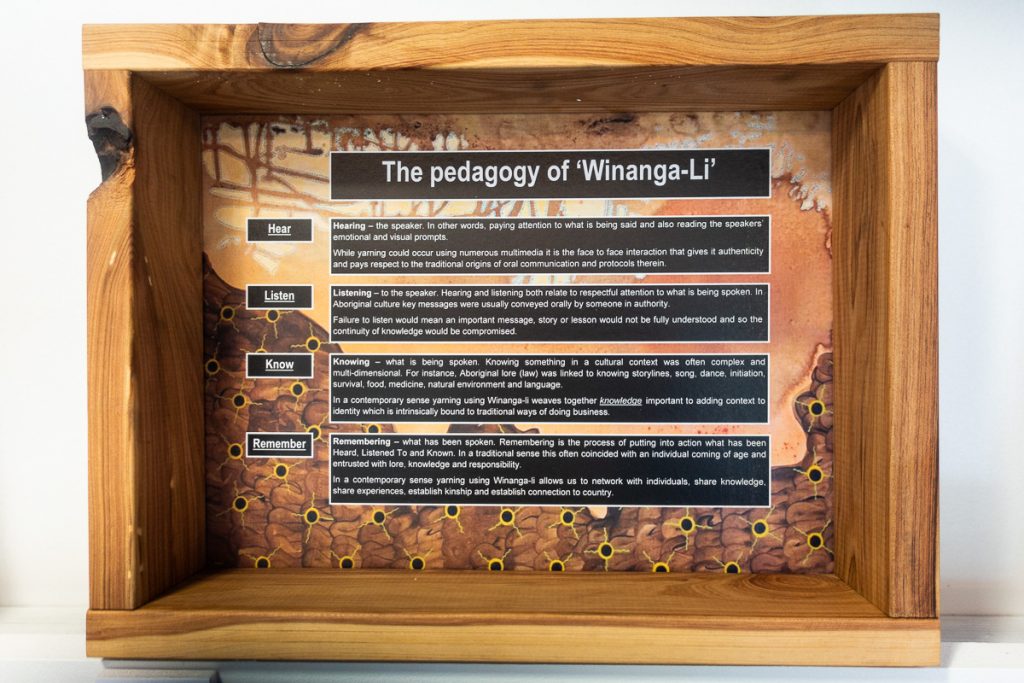

At the heart of the project is the use of the practice of ‘yarning’ to meet together, talk and to exchange ideas. Yarning involves both making of artefacts (in this case, weaving and making cordage, see example above) and conversation/storytelling (in this case, exploring a number of questions relating to the research). The underlying principles of the approach are based on the notion of Winanga-Li, a word/concept from the aboriginal nations of the North-West and Northern Tablelands of New South Wales, meaning hear, listen, know, remember. The starting point for the conversation related to kinship and land, with the initial question ‘where’s your mob from?’.

This is not the place to go into the process and outcomes of the research (that is covered in Munro, 2019), but rather to relate these specifically to the development of my project and photographic practice. The exhibition included a number of boxes made by Munro which ‘contain’ the principles, processes and outcomes of the project. It also included some of the weaving and other artefacts produced and Munro’s own artwork, including a number of tools and artefacts made through a combination of Aboriginal and European techniques (reflecting Munro’s own dual heritage, something that is difficult to address both within Aboriginal and European heritage communities). Visitors are encouraged to handle the exhibits. The exhibition thus addresses a range of complex issues in a way that places artefacts at the core and puts very different cultural understandings and practices alongside, and in dialogue with, each other.

The opening of the exhibition was accompanied by a workshop led by Munro, in which participants did some ‘yarning’ (that’s my cordage in the photograph above) while he mapped out the development and outcomes of the project (there was a longer workshop the following day around the making of a possum-skin cloak), and I was fortunate to be asked to make a response and give an appreciation of the work by Munro and the team at the Centre for Rural Health.

Like this project, the work I have done to date on my project has been collaborative and interactive. I have treated photographs as artefacts, using a portable printer to produce prints in situ, and encouraging members of the community to bring photographs of their own (and also to bring artefacts). Munro’s exhibition raises the question for me about the extent to which I want to make objects, and the production of artefacts, a more prominent feature of the work. Critical engagement with post-humanist theory, new-materialism and object oriented ontology gives a theoretical basis for engagement with objects, and the work done as part of the ‘Object Lessons’ course and consideration of the work by Fitzgerald et al (2018) on the ‘neuropolis’ reinforces both the conceptual and practical base for this (explored further in another post). Aboriginal conceptions of the relationship between human activity and the land/environment also holds potential, though how this relates/translates to the contexts within which I am working is an open question. Looking forward, Munro’s exhibition and workshop leads me to think more broadly about the potential outcomes of the Final Major Project, both in terms of a possible exhibition/event (which will be multi-faceted and multi-modal) but also about whether some sort of workshop (or interaction or performance) should be a component of this. That’s not to be settled here, but should be high amongst my own objectives for the Surfaces and Strategies module. Having run, for the second year, the national writing programme for equity practitioners in the week following the exhibition, I am also thinking about the relationship between my writing and my photographic work (and the relationship between the production of visual work and the process of writing – and, provoked by engagement with Ruscha’s art, text as a component, or primary focus, of visual work).

References

Fitzgerald, D., Rose, N. and Singh, I. 2018. ‘Living Well in the Neuropolis’, The Sociological Review, 64: 221–237.

Munro, S. 2019. Yearning to Yarn: The Artefact in Research. Newcastle, NSW: University of Newcastle.