The purpose of the tutorial was to take stock and set a clear direction for production of the FMP outcomes. Whilst the individual projects are moving forward, I want to allow them to take their own course (with their own timescales) and to view them as a resource for my over-riding (clearly defined) FMP project, which by necessity has to be completed by May 2020. The diversity and complexity of the projects provides a rich set of possibilities in terms of the focus for the project. The challenge at this point in time is to clearly define the direction and outcomes of the project.

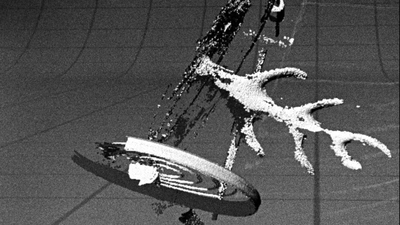

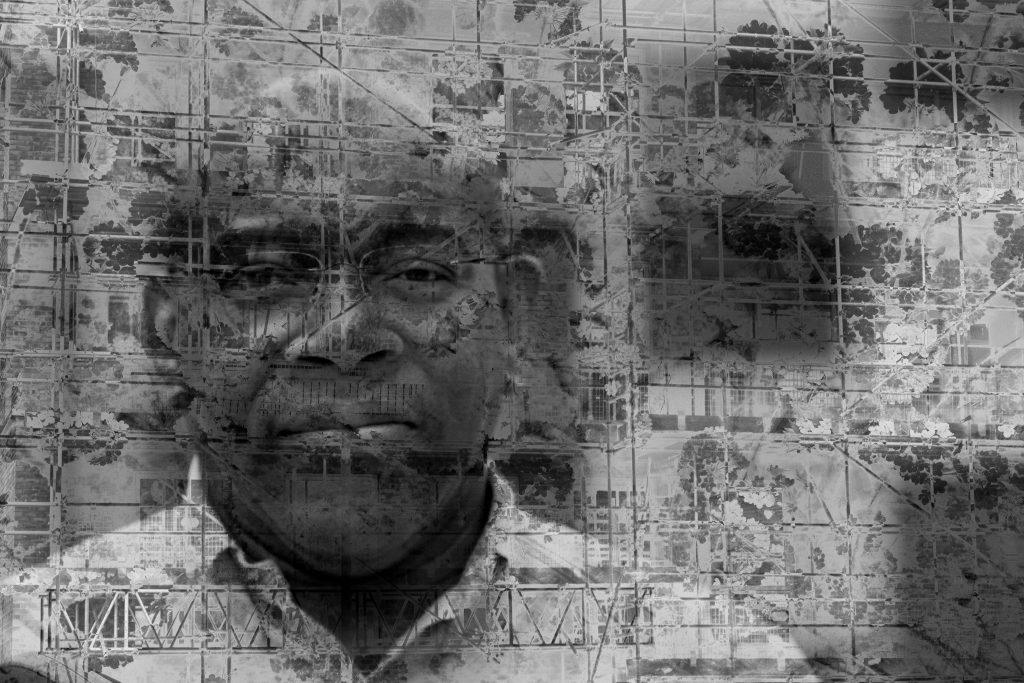

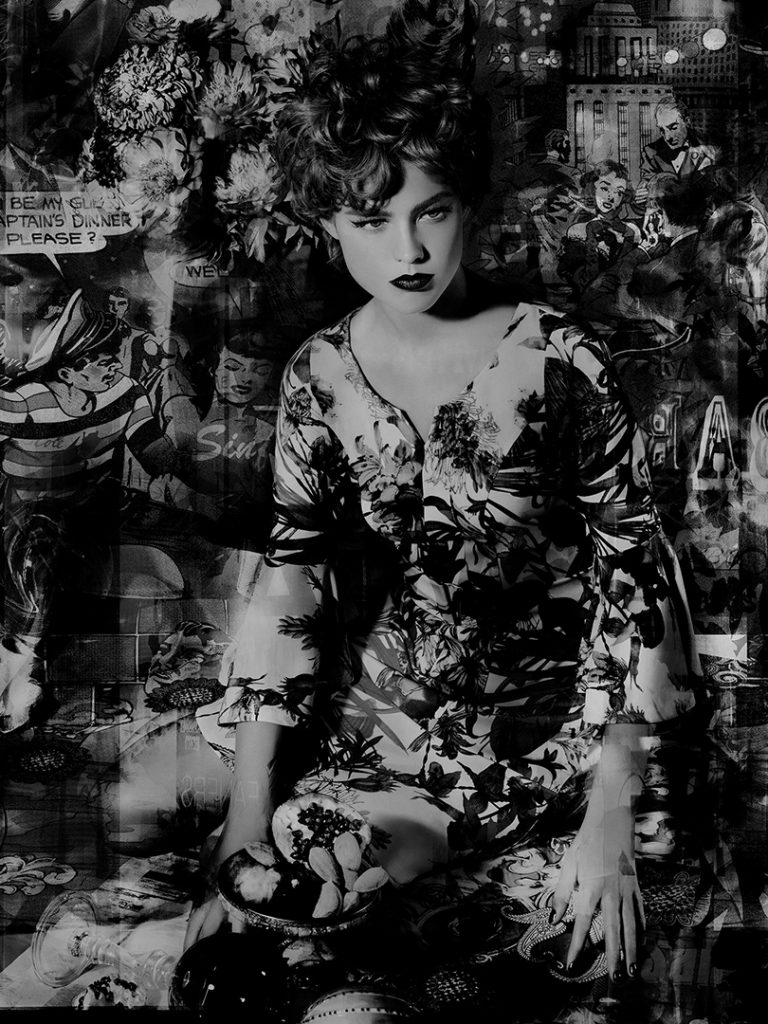

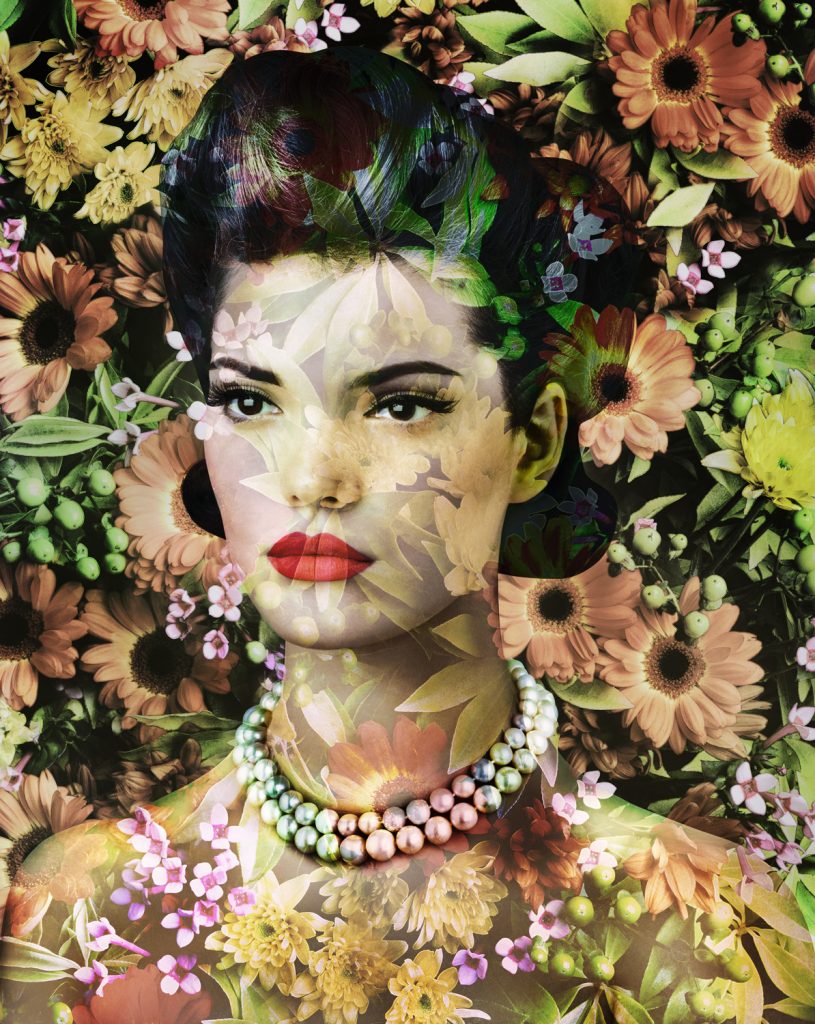

We discussed possible over-arching themes for the FMP project. The relationship between the natural and built environment and human activity (and, in particular, the ‘pushing back’ of the natural environment against human exploitation) appears to have most potential (for instance, in relation to the history of flooding of the marshland on which the Thames View, Thames Reach and Riverside estates are built, the recent fire on Riverside, the destruction of trees on the Gascoigne Estate, the pollution of land in the area by the coal-fired power station and other industrial units and so forth). This can be addressed through collaboration with selected participants in the micro-projects, and will involve archival work, environmental portraits, quotations, sound recordings, personal and official documents, photographs of the natural and built environment and of human activity relating to the place, developer and other images of current and future building, including CGIs. The work could focus on something like eight themes spanning both inter-twined environmental and human concerns (for instance, flood, fire, infestation, environment damage, mental health, migration, communication, isolation). Each theme could have a collaborator/informant, and would include material relating to their life world, trajectory and aspirations. The work could be presented as a multi-modal installation (see earlier discussion of the work of Edmund Clark and Janet Lawrence, for instance). The aim would be to invoke a sense of the relationships being explored, not a literal description. For that reason, and because of the complexity of the relationships, the exhibition (or other output) would not be explicitly themed (which raises the question of how to organise the work – do, for instance, I cluster the the biographical and archival material around the related composite image, what text is used and how, what is the relative scale of the images, and so on).

Specific issues raised in the tutorial:

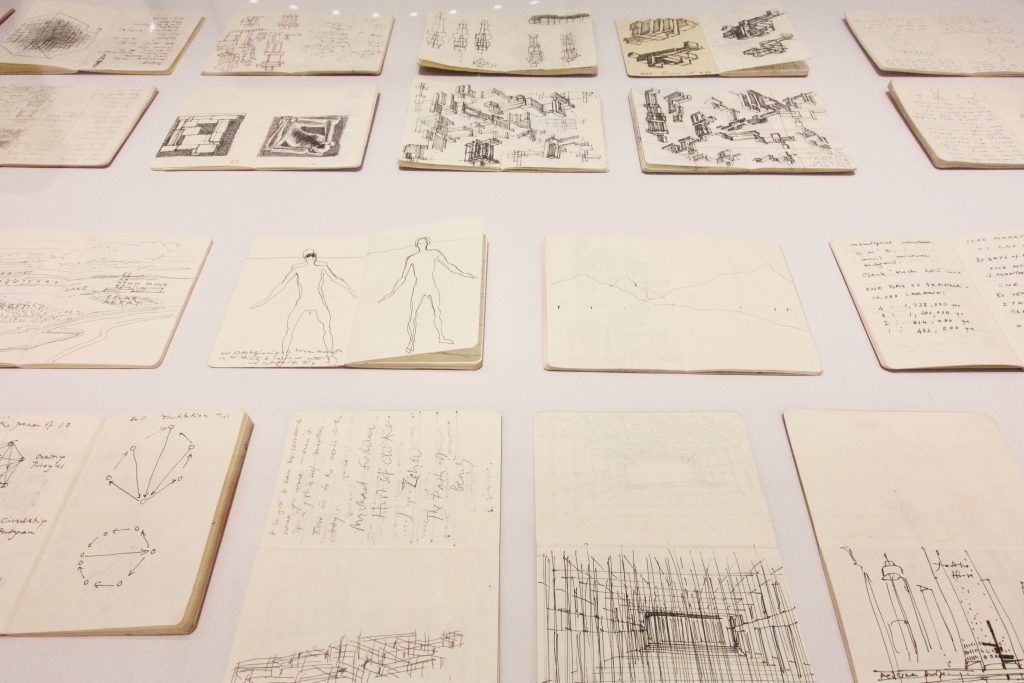

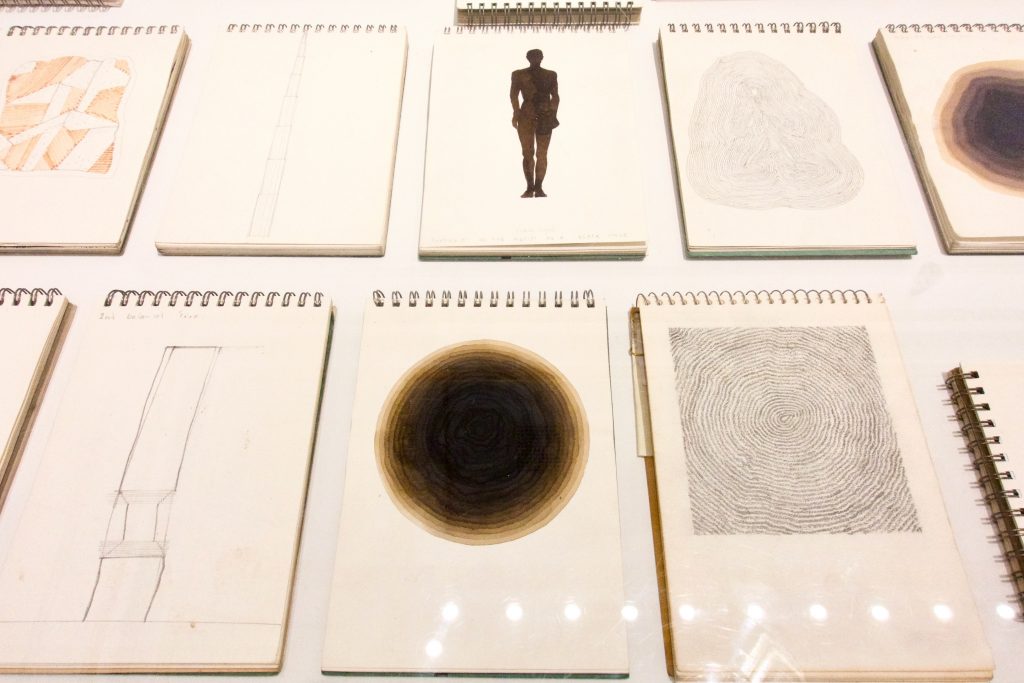

- I should use a sketchbook for exploration of both the images to be made and the layout of exhibitions and other public outputs;

- I could create a zine mock-up or similar for each of the themes/clusters of work, to explore ways of editing, sequencing and presenting the material.

- think about the ways in which the images will be presented, and experiment with alternatives (for instance, the use of projection). Need to take care over costs. Might think about a website, and other ways of creating resources for the online submission of the the final project.

- of the exhibition spaces explored, the Warehouse looks most promising in terms of flexibility. Another possibility is the new block at Barking and Dagenham College, where the Photography programme is housed, and which is in the process of being fitted out and occupied. There are a number of places where a temporary exhibition might be possible.

- check out work by Noemie Goudal (I saw her work in London last year). Particularly interesting is the scale of the work, and the use of frameworks and other structures for display. Her website includes lots of installation shots and is a good source of ideas.

- make more environmental images. Look at Gillian Wearing’s remaking of Durer’s weed paintings (for the video work Crowd, 2012) in relation to the exploration of plants and boundaries along Footpath 47.

- explore portraiture further. I am doing this as part of the work with the TWCP Citizen Action Group.