The collaborative activity this week provided a number of opportunities to develop my own practice as a photographer, in addition to getting to know the work of others in the cohort and to learn by working alongside them in a joint activity. An account of the focus of and motivation for the collaborative activity, and the method we adopted, is given in the post Looking for Derges: A collaborative project by Julie Dawn Dennis, Michael Turner and Andrew Brown. The final images produced are presented in the gallery post Collaboration project final images, and some of the source images I contributed are given in this gallery. In this post, I am going to focus on issues relating to collaborative production in the visual arts that arise from the collaborative activity and associated reading, not the procedural details of the activity.

My particular focus in this reflection is collaboration in the creative arts, and inter-disciplinary collaboration involving visual artists. The activity gave us some experience of working together as visual artists (our particular focus, drawing inspiration from the artist, Susan Derges, was explicitly concerned with the production of artistic work using photography).

Reflecting on the collaborative activity there appear to be a number of stages in the process: (i) reconnaissance and selection (scanning the interests of others and settling on one option amongst many, which involves judgement of the potential of each in relation to ones own interests); (ii) resolution of interests (shaping the focus together and adapting the activity to accommodate the range of interests and expertise of the group, exploration and research into artists, bodies of work and practices); (iii) determining working practices and timeline (figuring out how we work together and getting to know other members of the group, negotiating the stages of the project and the division of labour, agreeing communication, working practices, outcomes and milestones); (iv) production and negotiation (producing and sharing images, re-orienting the project in the light of experience, giving feedback, making selections); (v) constructing final images and narratives (determining and creating the final outcomes of the project including images, how they are presented and the narratives that accompany them and reflect on the process). As a pedagogic activity, carried out over a limited time period and not published or presented publicly, there are a number of issues that are less critical than they would be otherwise. For instance, the extent to which the focus and outcomes of the project fit with the artistic identities of the members of the group (and the extent to which these can be subjugated in the cause of the coherence of the project). Related to this is the issue of authorship, and whether the outcomes are attributed to the group or to individual members within the group. In our case, we were happy to attribute group authorship (everyone contributed images to each of the final products, and everyone produced at least one of the final composites). In a higher stakes collaboration, the question of attribution and ownership needs to be resolved at the outset, as potentially this can jeopardize the collaboration. It would be possible for individually attributed work to arise from collaborative activity. Alternatively, a collective identity could be produced for attribution of outcomes. Whilst this might be less of an issue in inter-disciplinary collaboration, where each participant has a clear sense of the relevance of outcomes to their particular areas of practice, there remains a question about the extent to which each participant influences overall and individual outcomes: are, for instance, visual artists attributed joint authorship of scientific papers, and are scientists given joint authorship of artistic work? I’ll return to this with examples in a later post, I think. I also wish to reflect on the limitation of the concept of artistic ‘practice’ in the light of the benefits and demands of collaborative work (I have in mind here the extent to which a fetishization of individual practice can limit productive collaboration in the arts). Finally, the tight timescale in this activity limited the extent to which (under pressure to deliver an outcome by the end of the week) we could engage in critical dialogue. This critical engagement is essential to fruitful collaboration, but with limited time can inhibit process. In any collaborative activity, it is essential to figure out how this critical dialogue is facilitated and managed (this is discussed by the Beth and Tom Atkinson in the course material).

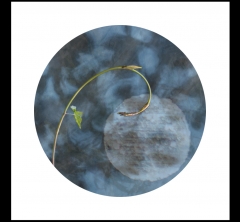

The benefits of this activity for my own practice as a photographer have been immense. I have learnt more about the work of Susan Derges through a practical engagement with it and discussion with others in the group, and I have learnt from working alongside other photographers. I have produced work that is very different from the work I have done in the past, and I think that collectively we have produced something we could (or at least would) not have individually. I have learnt from the process of collaborative production and the use of online tools to facilitate this collaboration at a distance. A certain facility with Photoshop was assumed by the group members, which I certainly do not have, and this has enabled me to explore Photoshop and develop my ability to produce composite images. In the webinar, we received very positive feedback from other members of the cohort, who were impressed by the quality and originality of the outcomes, particularly in the time available. Within the group, we were concerned about the ‘muddiness’ of the complex composite images, in comparison to the simplicity and clarity of Derges’s camera less images. For me, this warrants further exploration of the the use of camera less and other alternative processes in producing images. So whilst we were pleased with the outcomes, we can see a number of areas for development that arise from this.

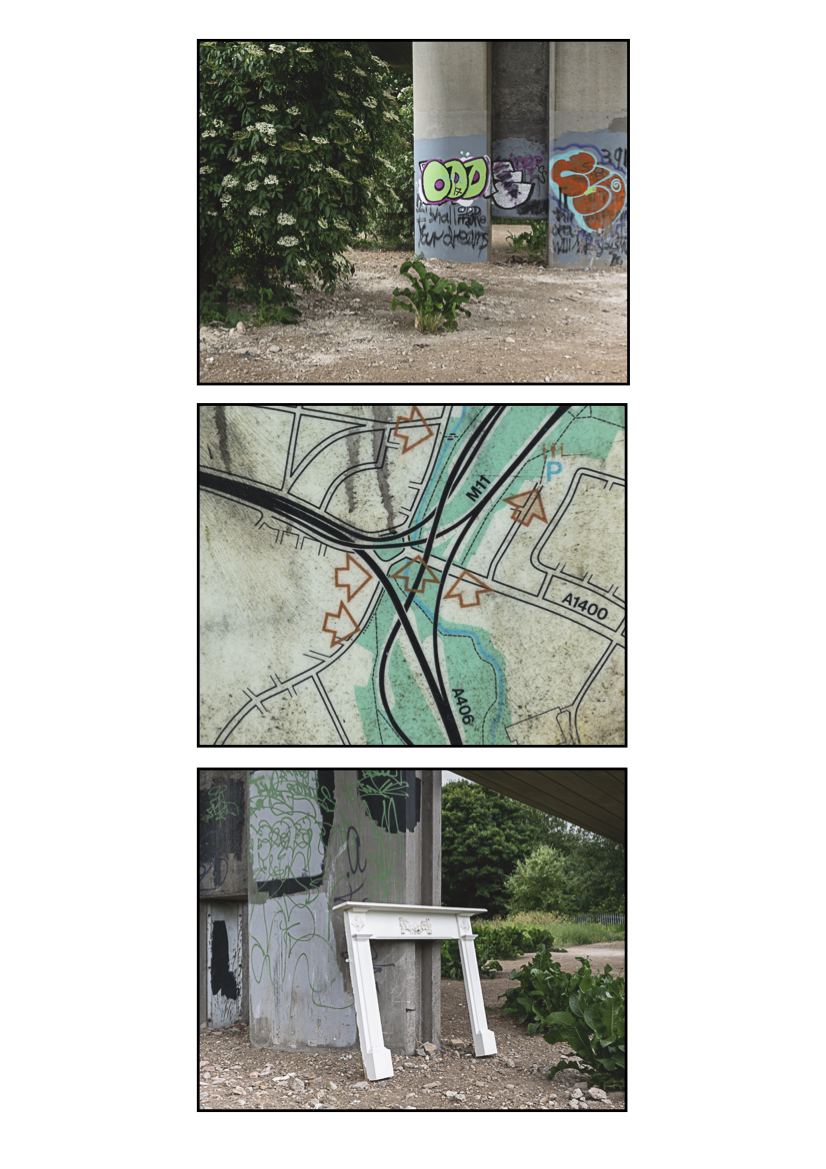

Other groups took a very different approach. One group did produce a composite image from three minimalist images produced by the group members. There was some discussion about the extent to which this final, highly complex and enigmatic, image was successful. Suggestions were made about how the image might be cropped or re-orientated, and the extent to which lack of a clear focus for the image was a strength or a limitation, with viewers hunting around the image to make meaning. The third group presenting at the webinar produced a sequence of impressive graphic black and white photographs from domestic settings, interleaved with quotes from photographers and theorists about the process of photographic observation. The juxtaposition of the images produced by different members of the group was particularly striking. This represented a very different, but no less effective, form of collaboration, where individuals with a shared set of interests contributed images to a final collective presentation.

From the webinar discussion, I have no doubt that the interaction that took place in the process of production of a collective outcome was a great value to the members of all the groups in the development of their own work. There is clearly greater scope for critical dialogue about our work, but, at this early stage in the course, I feel we are in the process of developing greater confidence in our own work and our relationship with other members of the cohort.