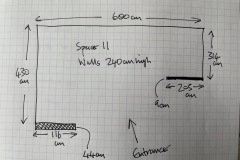

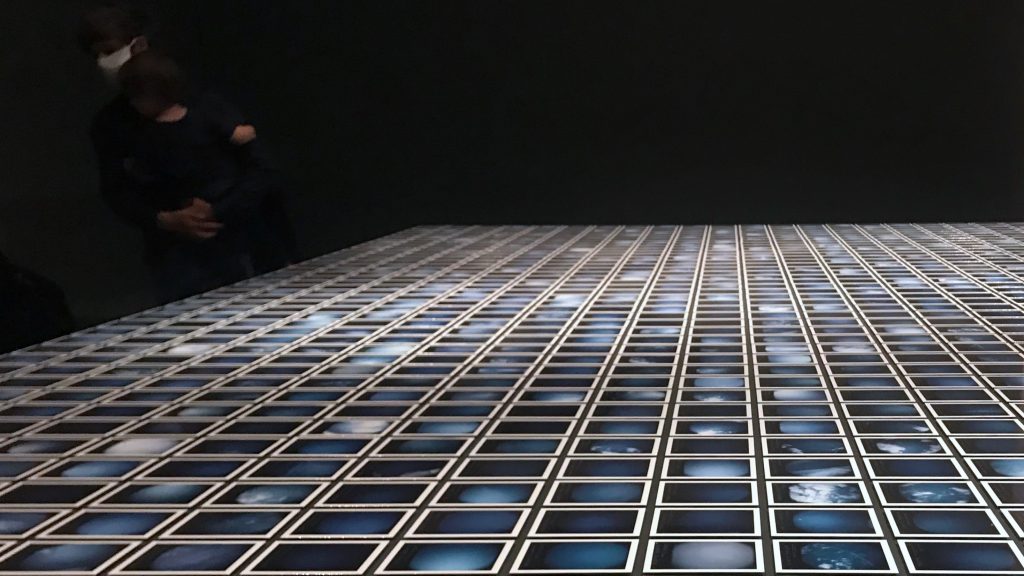

Focusing on presentations, writing and getting on with producing new work left me relatively unprepared for the DFA Showcase exhibition. I decided to present work from two series from my River Roding residency: Habitation and Single-use. Both are still work in progress, so I hadn’t (and still haven’t) given any deep thought to how they might be presented in a gallery setting. I made an early commitment to mounting the work directly on the wall (using Wolfgang Tillmans style tape hinges for the prints up to A3+ size and bulldog clips for the larger prints), which relieved me from the pressure, and expense, of mounting and framing. I also took the opportunity to experiment with digital upscaling for the larger prints, and using different papers for the Single-use series (settling on a wonderful bamboo paper by Awagami). I also had to take into account the relatively short time available to install and take down the exhibition, and the (disappointing) fact that university covid measures restricted us to only three guests to view the exhibition (though is was good that DFA students could view and discuss each others work).

Alongside the Single-use prints, I installed a short animation with soundscape (running on a Raspberry Pi feeding a 32″ monitor with speakers). The animation showed the morphing of images of plastic bags entangled in trees along the Roding shot with flash and naturally backlit. The soundscape was a binaural field recording made at the site of the photographic work. The unifying theme of the work was the idea of ‘matter out of place’, though this was relatively weakly framed.

The experience of mounting the exhibition, and seeing work produced by others in the later stages of the programme, made it clear that I have to focus more on the production of work for the showcase in subsequent years. Gallery exhibition is not likely to become a major part of my practice, which will continue to focus more on placing the work in unconventional exhibition spaces and keeping public engagement with the work close to its site of production. On the final day of the exhibition, we received feedback from Lewis Paul (a film-maker based at Leeds Beckett University, and a graduate of the DFA programme). This was billed as a Guest Seminar, but was more akin to a critique in which we moved from one exhibition space to another and engaged with Lewis’s reflections on and questions about the work.

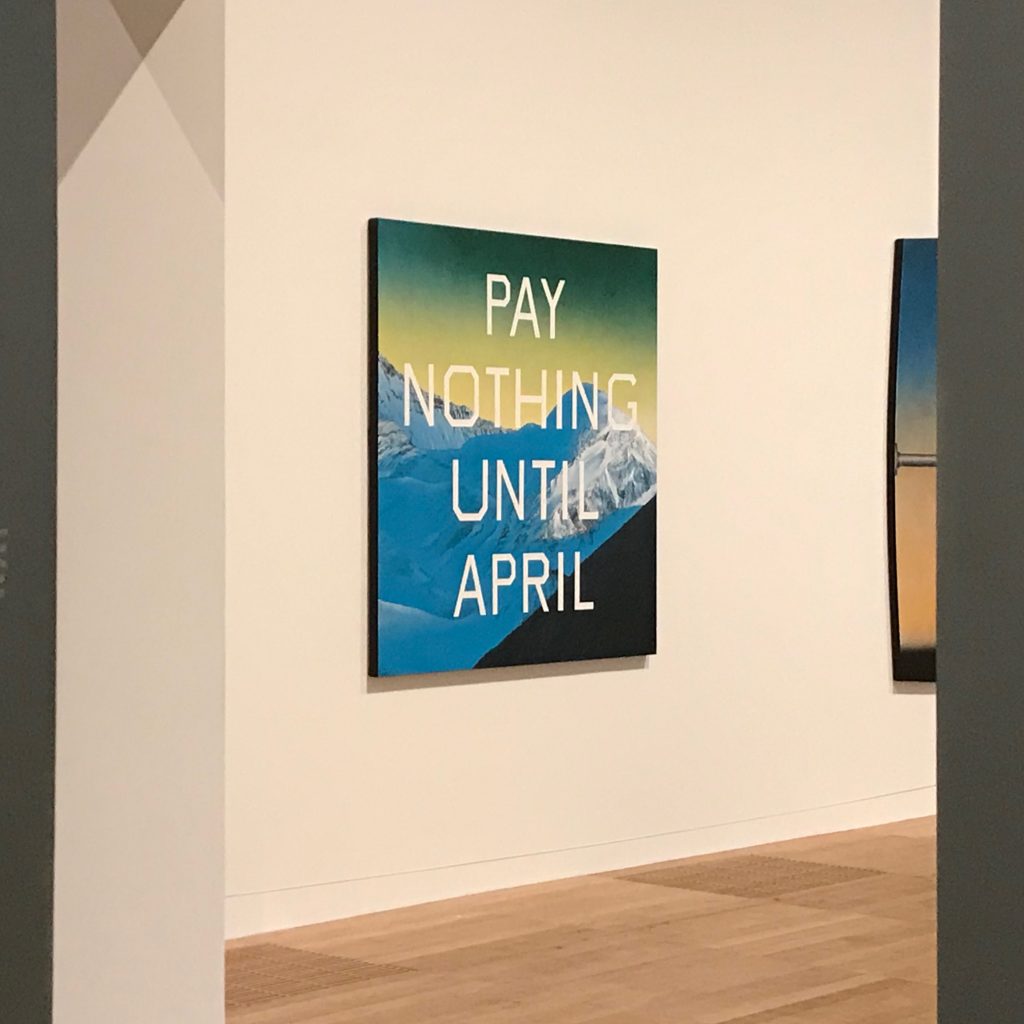

In his notes on my work, Lewis observed that whilst diverse methods of making are clearly central to my practice, I need to give greater thought to the staging of the work and how this relates to what I am attempting to communicate or invoke. He also raised the related issue of the relationship between evidence and aesthetics and, in particular how evidence can be transformed into the poetic (or rendered as poetic). His key point was to think more carefully about widening accessibility of the work and consideration of how the work is staged and accessed. Good points, I think, and important to consider in relation to my experience to date of presenting work in non-gallery spaces. He suggested looking again at Eisenstein montage theory (which harks back to my early channel mixing work and the influence of Moi Ver and Peter Kennard in the juxtaposition of images), and also to help think through the relationship between the soundscapes and the visual work (citing work by Chris Watson). In discussion, he also raised the issue of the titling of work as a way of provoking interest and engagement (citing the YBAs use of titles that intrigue). In his more general comments he positioned the contribution of DFA research in interesting ways, for instance the strategy of identifying research ‘cul de sacs’ that other forms of theory and disciplinary research have been unable to address, but which can be addressed, in practice, through our own artistic work. Most importantly, he reinforced the need, in a practice-based, professional doctorate, to demonstrate how my work makes a specific contribution.