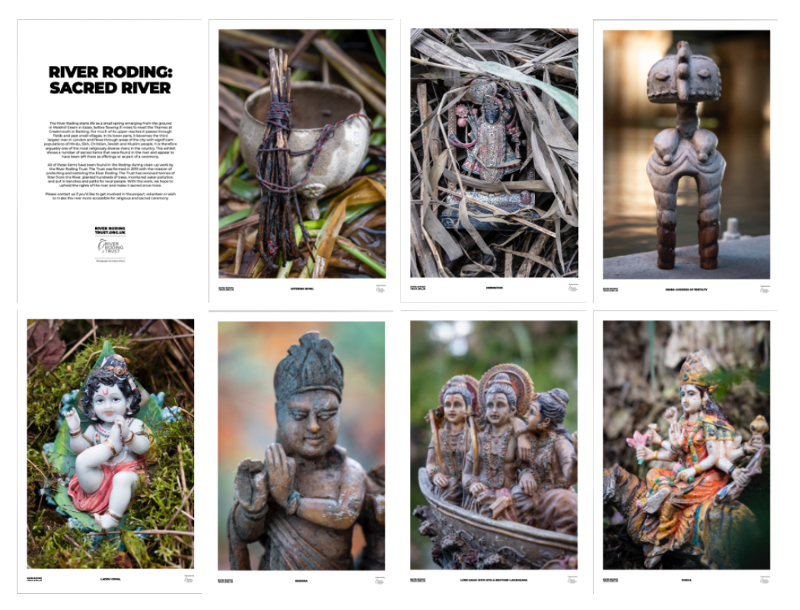

As described in earlier posts, I use photography with community and activist groups in a variety of ways, including the use of participant photographs to explore life-worlds, collaborative production of images for advocacy and the production of images as a personal lyrical response to specific urban contexts in flux. The means of presentation of the work and engagement with an audience mirrors the process of production in the creation of multimodal collections around a theme, which are offered to others as a resource for the production of narratives, and the use of non-gallery spaces for pop-up exhibitions and workshops. These exhibitions and workshops are as much a part of the process of producing my work (in that they enable feedback on work presented which in turn influences future iterations of the work and provide opportunities for collaborative practice) as they are outputs (in the dissemination of the outcomes of the projects). In the early stages of each project the primary focus is on building relationships and trust, leading to identification of photographic work that would be of use to the community. The resulting repositories of images form a resource that can be used by the community in press reports, campaigns, promotions, funding applications and so on. For example, I made images of religious artefacts found in clearing the banks of the river for the River Roding Trust, which have been used in making presentations, for instance to the local Interfaith Forum. They now form the basis of an exhibition available to schools and community groups and is being used to advocate for the care of the river and surrounding area (Figures 1 and 2).

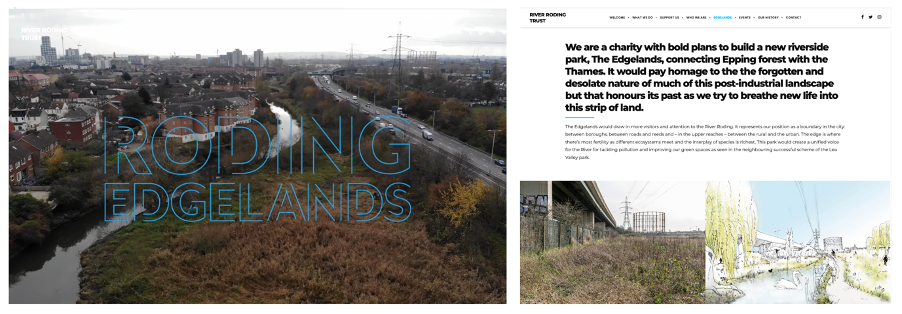

Other images made in the area are being used in funding applications, for instance to Transport for London for the creation of a river path and campaigns, for instance by the CPRE London for ten new London parks (Figure 3).

Alongside building these repositories, I am doing archival research with local libraries and museums (delayed due to the furloughing of archive staff), collecting artefacts and making images and field recordings which will form the basis for my own work to be exhibited in the area. This form of exploration through physical immersion in a place and exploration of its materiality, history and inter-connections bears a resemblance to the process of Deep Mapping (Bloom and Sacramento, 2017). At the initial speculative stage in the project, I have produced several series of photographs, in this case exploring the entanglement of the human and the more-than human in this particular place, for example the Home series (Figure 4) which explores a tragic burnt-out encampment in the bushes by the river and the Carrier series (Figure 5) focusing on plastic waste entwined with the branches of trees between the road and the river.

Other series also involve experimentation with the form of photographic image making, particularly relevant given proximity to the former Ilford Limited photographic materials manufacturing plant, including the Colour Shift series (Figure 6), which involves improvised home processing and the Plant Phenols series (Figure 7) which uses Karel Doing’s (2020) phytogram process with Ilford films and papers and locally foraged materials.

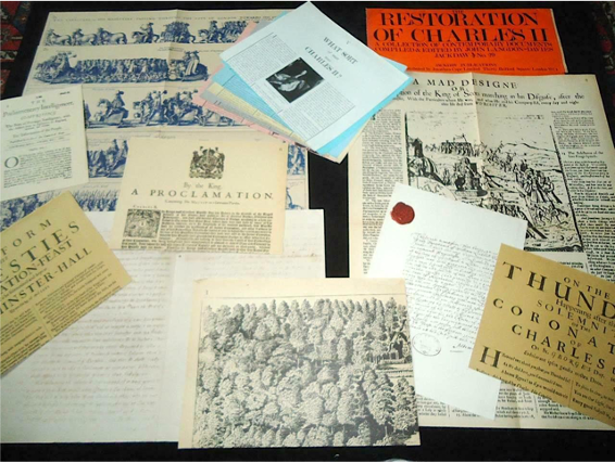

With pandemic management measures currently in place, this work will be exhibited outside (for instance, along the pathway alongside the river and on concrete plinths between the highway and the river). Archive collections, artist books and portable exhibition materials will also be created, and these will be used in workshops (which will also feed material into the collections). Inspiration for this comes from five principal sources. Firstly, collections of facsimiles of historical documents and other images, texts and artefacts that are used for first-hand engagement with materials in developing an understanding of historical periods and events (for instance, Jackdaws – see Figure 8).

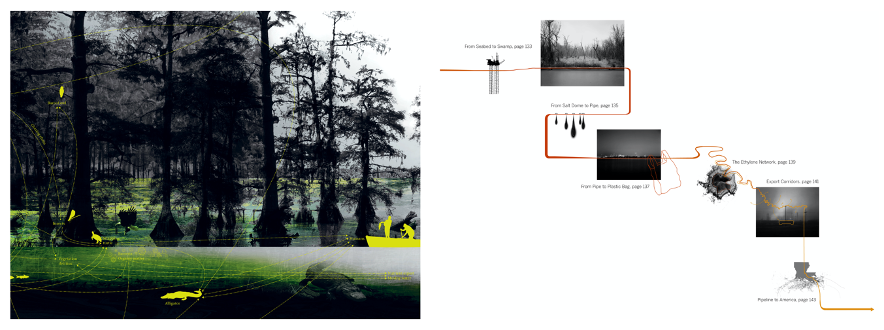

Secondly, the collections of artefacts and images carried by migrant and displaced groups, explored for instance by the Refugee Hosts project (refugeehosts.org). Thirdly, the use of collections and portable exhibitions by artists, such as Marcel Duchamp’s La Boîte-en-Valise (1935-41) and Dayanita Singh’s Museum Bhavan (2017), which consists of box sets of accordion books and prints stored in bespoke cases with portable stands, enabling others to construct their own exhibitions from her work. Fourthly, indigenous forms of pedagogy, such as the use of artefacts and collective sense making in Australian aboriginal communities explored by Simon Munro and colleagues in the Yearning to Yarn project (Munro, 2019). Finally, the juxtaposition of photographic images alongside maps, infographics, illustrations, artefacts and other materials, for instance in Richard Misrach and Kate Orff’s multi-disciplinary Petrochemical America (see Figure 9) and installations and books such as Mark Dorf’s Kin (Dorf, 2018).

As Palmer (2013) has pointed out

‘there is nothing inherently more democratic or progressive about collaborative photography; the photographs of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in 2004 were, after all, a product of a group exercise in torture. However, thinking about photography in collaborative terms invites us to reconfigure assumptions about the photographic act in all its stages’. (pp. 122-3)

In writing about her collaboration with photographers Wendy Ewald and Susan Meiselas, Ariella Azoulay (2016) cautions that collaboration can, indeed, become ‘a weapon in the hands of an oppressive regime’ (p.188). For Azoulay, collaboration is inherent in all photography, regardless of the intentions of the photographer, as there is always some form of encounter in the act of making a photograph. This alerts me to pay attention to the form of encounter, and questions of authorship, ownership, knowledge and rights, and more broadly the ethical issues that these encounters raise for all forms of artistic practice. The ethical issues raised by collaborative work have been explored in detail by others working in this way, for instance Anthony Luvera (see, for instance, Ewald and Luvera, 2013, and Luvera, 2008) and Gemma Turnball (2015). Whilst I am not engaged with the kind of social documentary and representational form of collaborative photography described by Turnball, it is important to learn from and attend to the issues that this work raises regarding authorship, agency, expectations and form of relationship with participants. These are equally important in understanding the shift to usership (Wright, 2014) and what this means for plurality in artistic practice (Lahire, 2011) more generally.

This reflexive exploration of plurality in art practice through production of and reflection on my own work requires the creation of a range of multi- and trans-disciplinary projects over the course of the doctorate. To this end, I am building on existing links and networks to explore opportunities for collaborative work with researchers at UEL and UCL, with London Prosperity Board members and with community groups in Newham, Redbridge and Barking in Dagenham, and around the Olympic Park.

References

Azoulay, A. (2016) ‘Photography consists of collaboration: Susan Meiselas, Wendy Ewald, and Ariella Azoulay’, Camera Obscura, 31(1), pp. 187–201.

Bloom, B and Sacramento, N. (2017) Deep Mapping. Auburn, IN: Breakdown Break Down Press. Online at https://www.breakdownbreakdown.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/2017-Deep-Mapping-bookweb.pdf [accessed 20.03.21]

Doing, K. (2020) ‘Phytograms: Rebuilding Human–Plant Affiliations’. Animation, 15(1): 22–36.

Dorf, M. (2018) Kin, New York: Silent Face Projects.

Ewald, W. and Luvera, A. (2013) ‘Tools for sharing: Wendy Ewald in conversation with Anthony Luvera.’, Photoworks Annual, (20), pp. 48–59.

Kress, G. (2009) Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Routledge.

Lahire, B. (2011), The Plural Actor, Cambridge: Polity.

Luvera, A. (2008) ‘Using children’s photographs’, Source, Issue 54, Spring 2008. Online at http://www.luvera.com/using-childrens-photographs [accessed 11.11.20].

Misrach, R. and Orff, K. (2012) Petrochemical America, New York: Aperture.

Palmer, D. (2013) ‘A collaborative turn in contemporary photography?’ Photographies, 6(1), pp. 117–125.

Singh, D. (2017) Museum Bhavan, Göttingen: Steidl-Verlag.

Turnbull, G. R. (2015) ‘Surface tension: Navigating socially engaged documentary photographic practices’, Nordicom Review, 36, pp. 79–95.

Wright, S. (2014) Toward a Lexicon of Usership. Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum. Online at https://www.arte-util.org/tools/lexicon/ [accessed 10.11.20].