In her review of contemporary photography and the environment, curator, writer and art historian Kim Knoppers (2020) draws predominantly on what she calls photography plus or extended photography. Her reasons are, firstly, that she is committed to multi-and inter-disciplinary work in which the medium is correlated with the topic being addressed, and, secondly, that she feels that photography might not be ‘fully equipped’ for exploring the environment and, in particular, ecological crisis. The limitations of photography lie in part in its historic implication, as a representational technology, in the separation of humans from the environment as spectacle, for instance in the epic landscape photographs of Ansel Adams. It is no longer tenable, she argues, to aspire to change behaviour in relation to the climate crisis through the use of ‘a few beautiful photographs’. She recounts the difficulty she has had in finding compelling images that deal with the effects of human activity on the environment and adequately invoke the habitually hidden interplay of science, power, politics, law, economics and technology. The danger is that, she argues, seeing images that we feel we have seen before, no matter how captivating, will fail to provoke new ways of thinking about the place of the human in the world and prompt urgently needed action. To address the complexity of overturning long held assumptions about human-centred progress and form a closer connection with the earth and more-than human entities, contemporary photographic artists have to seek new ways of conveying non-human centred narratives and thus incorporate other modes of artistic production into their work. Examples of artists who juxtapose photographic images with other media in this way include Mark Dorf, whose work incorporates artefacts, text, video and music (Figure 1).

This work also commonly involves collaboration across disciplines. The work of Australian artist Janet Laurence exemplifies, and amplifies, this embrace of interdisciplinarity and multimodality. Laurence not only exemplifies working across disciplines, but also actively engages with contemporary theory in the social sciences and humanities. Through her own writing and joint authorship of academic papers she makes a distinctive contribution to the understanding of plant life and its relation to human activity (see, for instance, Gibson, 2015b).

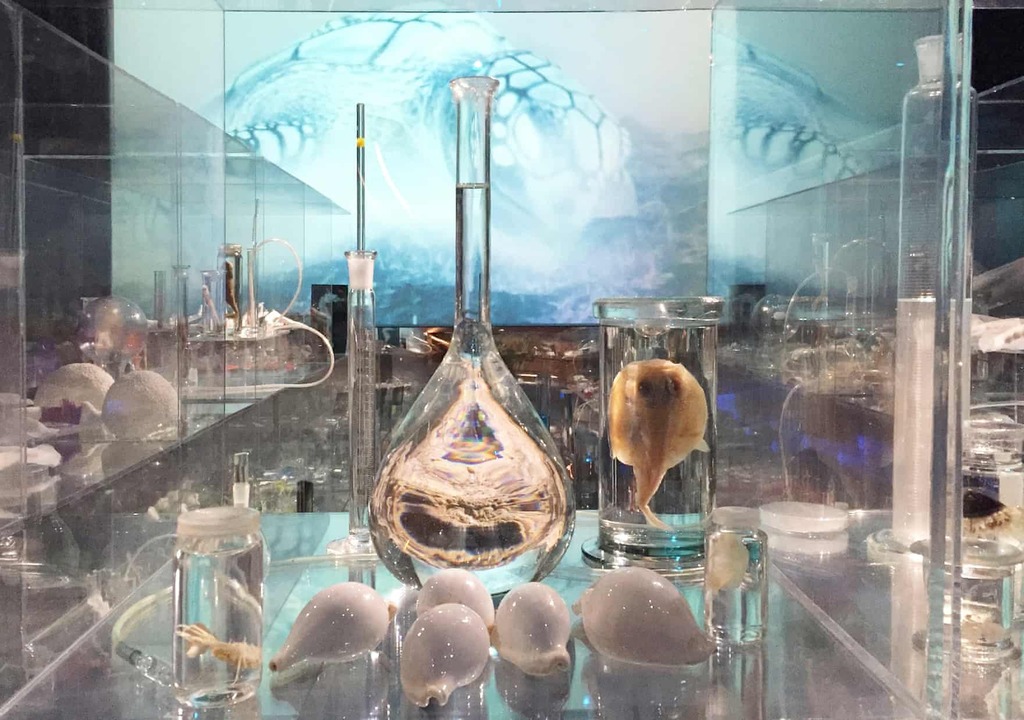

My first knowing encounter with Janet Laurence’s work was the exhibition After Nature, a retrospective, plus a major new work, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney (1st March to 10th June 2019: Figures 2 and 3). I subsequently recalled that I had seen her installation at Changi Airport in Singapore (The Memory of Lived Spaces, T2 Changi Airport, Singapore, 2008). It was clear that there is a substantial overlap with a number of emerging themes in the development of my own work, albeit in a very different context, and with a different emphasis. Engaging with, and reflecting on, Laurence’s work has enabled me to make a number of connections between aspects of my artistic work and conceptual approach. In particular, the exhibition, and subsequent research into Laurence’s work, has enabled me to think more clearly about multimodality in the arts and the role of the arts in multi- and inter-disciplinary enquiry. It also provokes me to consider how I might present the outcomes of my work, and how this relates to my methodology and broader conceptual framework.

This exhibition included key works by Laurence, from early pieces using metal plates, minerals, organic substances and photographs mounted on lightboxes (exploring, for instance, the periodic table), through installations from the 2000s featuring plant and animal specimens and ‘wunderkammer’ (box of curiosities) environments, to a contemporary commissioned piece, featuring floor to ceiling ‘veils’ printed with tree images, arranged in three concentric rings through which visitors can walk, and quasi-scientific collections of plant samples and apparatus (a herbarium, an elixir bar and a botanical library). As the curator’s notes state, Laurence explores ‘the interconnection of all living things – animal, plant, mineral – through a multi-disciplinary approach’ using ‘sculpture, installation, photography and video’ (Kent, 2019). As Gibson (2015a) notes, Laurence has a ‘biocentric’ view of the world, and that, through incorporation of live biotic material in her work, she goes beyond just the entanglement of the human and the (other non-human) natural to focus on questions of care and the possibility of repair and reparation.

Gibson and Laurence (2015) explore the relationship between this work and contemporary posthumanist theory (and this is further explored by Gibson, 2015a and 2015b). Focusing on the piece Fugitive (2013: see Figure 4) they argue that Laurence entangles the (human) viewer in the natural, making us all complicit in ecological/environmental decline, but does so in a way that resists re-assertion of a culture/nature divide. The collection of organic and animal material, and the multi-modal form of the work, challenges both scientific objectivity and human subjectivity. An explicit influence here is Karen Barad’s (2012) non-dualist ontology, which decentres the human subject in a way that avoids simply inverting humanism. Blurring the boundaries between the human and non-human is not sufficient, they argue, invoking Barad’s idea of ‘intra-action’.

‘The matter is there in the forceful enactment. The reason Barad’s concept of intra-action is so exciting is because her quantum physics expertise develops into an exploratory elaboration of this idea into the realm of phenomenology. In other words, she sees phenomena as quantumly entangled, but this is not individual entities becoming entangled but where intra-acting components are inseparable or indivisible. Perhaps, the entities don’t come together and become entangled, they already were entangled primordially’ (Gibson and Laurence, 2015, p.47).

In her largely site-specific work, Laurence produces places where crossing-over can take place, where difference can be questioned, and entanglement experienced. There is also a sense of slowing down and focusing of attention when presented with the sheer volume (Figure 18), and forms, or artefacts, both veiled and brightly illuminated. As Miall (2019) notes, this effect is particularly marked in Laurence’s site-specific works,

‘The spatiality of installations, their insistence on embodied contemplation and the way in which they engender a haptic, bodily awareness through overlaying the processes of memory and perception with the work’s materiality, are central to the transformative experience of Laurence’s public projects.’ (p.86)

Engaging with Laurence’s work has influenced my own thinking in a number of ways. It has helped me to think more clearly about the link between posthumanist theory and art, as it relates to the kinds of contexts I am exploring. She highlights the co-dependence of the human and the natural and the reciprocity of care (which in turn, and in intention, undermines the human/natural dualism). Posthumanism is not anti-humanism, and, for me, the challenge, artistically, is to explore the de-centring of the human whilst maintaining an active commitment to equity and social justice. There is no necessary contradiction between non-anthropocentric view and human equity, in fact, for the latter to be sustainable the former is a necessity. Engagement with Laurence’s work has given me some insight into how I might provide a sense of entwinement of individuals and communities in place, and the alienating nature of contemporary developments.

References

Barad, K. (2012) ‘Nature’s Queer Performativity.’ Kvinder, Køn og forskning/ Women, Gender and Research. No. 1-2: 25-53.

Gibson, P. and Laurence, J. (2015) ‘Janet Laurence: Aesthetics of Care’, Antennae: The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture, (31), pp. 39–52.

Gibson, P. (2015a) ‘Plant thinking as geo-philosophy’, Transformations: Journal of Media & Culture, (26): 1–9. Online at: http://www.transformationsjournal.org/journal/26/02.shtml [accessed 10.11.20].

Gibson, P. (2015b) Janet Laurence: The Pharmacy of Plants. Sydney: NewSouth Books.

Kent, R. (2019) After Nature: Janet Laurence. Online at https://www.mca.com.au/artists-works/exhibitions/829-janet-laurence/ [accessed 10.11.20].

Knoppers, K. (2020) ‘Contemporary Photography and the Environment’, Self Publish, Be Happy Online Masterclass, 22nd October 2020.

Miall, N. (2019) ‘The Constant Gardener: On Janet Laurence’s Site-Specific Works’, in Kent, R. (ed.) Janet Laurence: After Nature. Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, pp. 83–95.