There are a number of reasons for choosing Fay Godwin (1931-2005) as one of the three photographic artists in this exercise. I have a longstanding interest in her work, especially her photographs of Romney Marshes (Godwin & Ingrams 1980) and the Saxon Shore Way (Sillitoe & Godwin 1983), having grown up in East Kent.

Through this exercise, I want to both reassess her work in the light of subsequent shifts in photographic theory and practice, and broader political changes particularly in relation to the environment, and consider whether, and how, her work has influenced my own photographic practice. Godwin, like me, came to photography from another professional field (publishing in her case) and did not have any formal training in photography or the visual arts. In a 1983 interview, she stated that:

‘I don’t have an academic approach to photographs, and I’m not very interested in theory. I’m much more interested in working. The old question about whether photography is an art is a silly question. I’ve been called a Romantic photographer and I hate it. It sounds slushy and my work is not slushy. I’m a documentary photographer, my work is about reality, but that shouldn’t mean it can’t be creative.’ (quoted in Fowles 1985: xii)

The primary means of dissemination of her work has been in books produced collaboratively with writers. In this analysis of her work, however, I am going to focus particularly on two volumes which foreground her photographs, and where the text plays a supporting role: Land (Godwin 1985, based on an exhibition surveying her work and published as a book with an essay by John Fowles and introduction by Ian Jeffery) and Our Forbidden Land (Godwin 1990, for which Godwin provides her own substantial introduction and text alongside the photographs, with poems by other authors, and which highlights her activism around access to land in her role as President of the Ramblers Association). I have particular interest in the relationship between photography and writing, and also on the use of photography in social action and advocacy. Here, though, I want to reflect on how Godwin’s approach and photographic sensibility might be re-contextualised from predominantly rural to contemporary urban contexts, in which the ownership of and access to the land have become a particular concern. I also want to position the work in relation to contemporary debates about the relationship between art and environmental activism (see, for instance, Demos 2017)

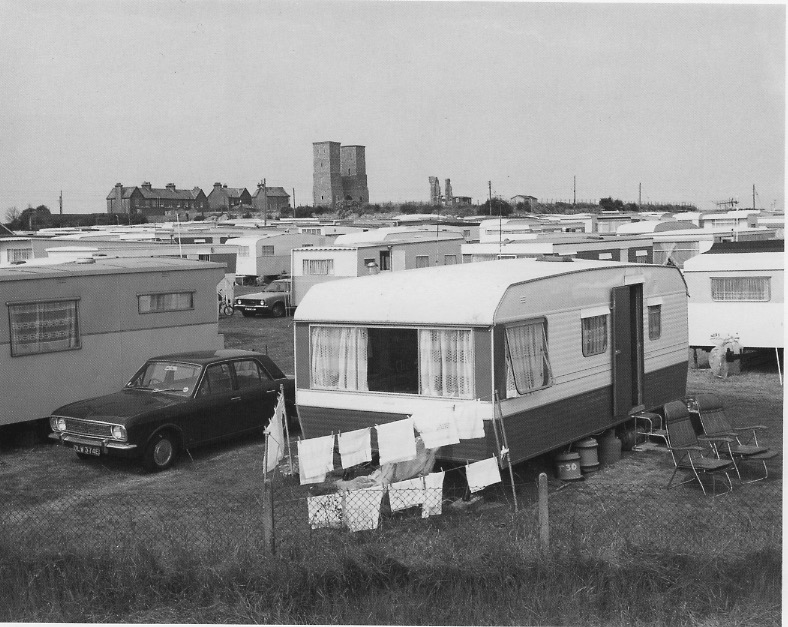

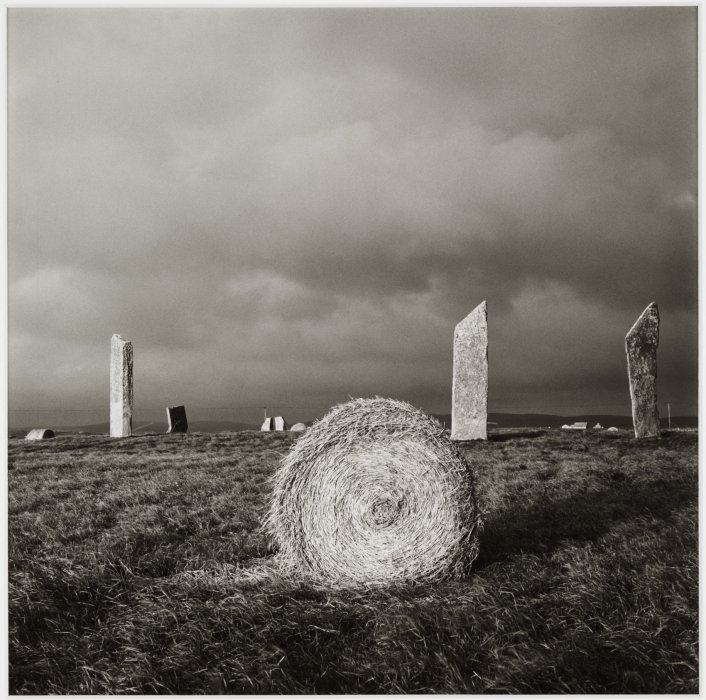

As Fowles (1985) points out, many of Godwin’s images play with time, juxtaposing the timeless landscape with present day (or earlier) evidence of human activity (buildings, infrastructure, artifacts, vehicles, detritus, but never people), but in layers or in proportions that convey or create tensions.

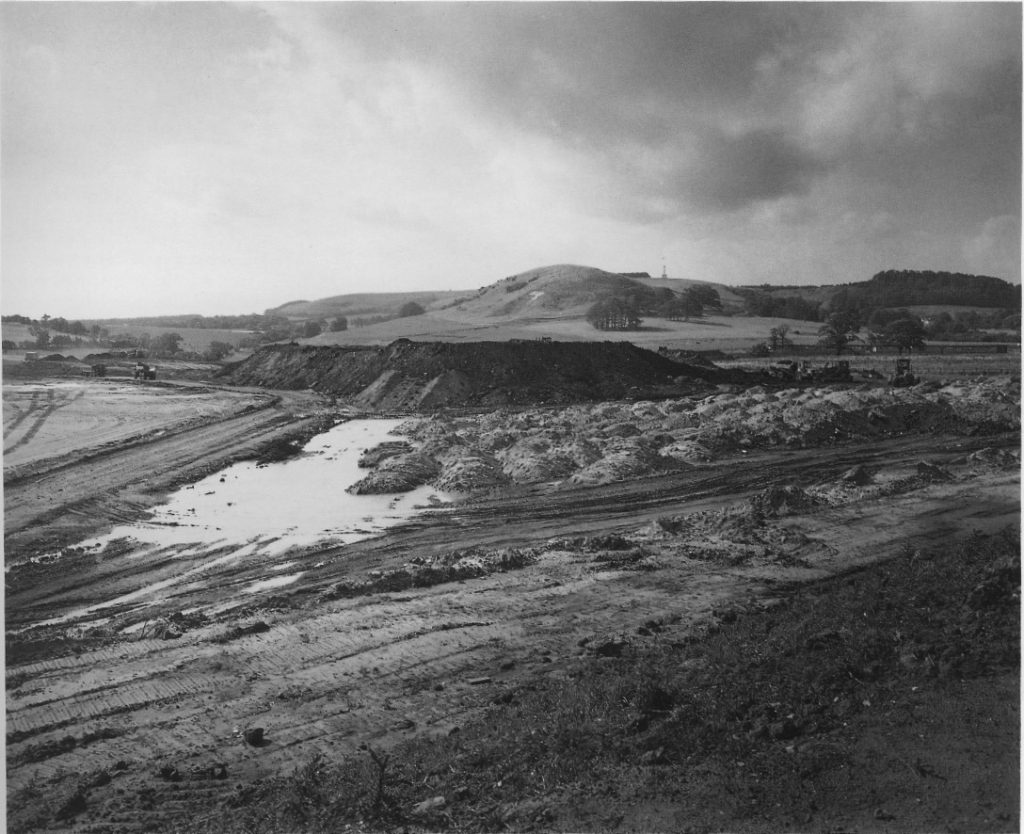

Godwin resisted being seen as a landscape photographer, preferring to be considered a documentary photographer. Her interest is not in the landscape per se (and thus, she has no interest in producing conventionally aestheticised landscape images: in a 1986 South Bank Show interview she states that she is ‘wary of the picturesque’), but rather in human engagement with, material impact on and use of the landscape. Ian Jeffery (1985) highlights the bringing together in the frame of the wild and the cultivated, and the antagonism and discordance, in Godwin’s work, between the land and the human, between the wilderness and habitation. Encompassing the formal arrangement of elements in the frame, the subtlety of symbolism and the careful sequencing of images, Jeffery demonstrates how the work presented in Land clearly goes beyond documentary into the domain of photographic art, drawing out resonances with other photographic artists such as Paul Strand and Walker Evans. The images are not immediately arresting, but do draw in the viewer and repay active engagement, with, as Jeffery notes (South Bank Show 1986), any romantic elements of the landscape (such as clouds and distant hills) offset by, often foregrounded, practical and everyday elements. Unlike Sugimoto’s work, discussed in an earlier post, there is no apparent underlying conceptual basis to discrete series of images in Godwin’s work (if the corpus is to be divided into series, then each would be geographically defined, rather than conceptually, with the exception of the later, environmentally focused work), there is a clear orientation to the landscape and visual sensibility, which constitute Godwin’s artistic vision. There is also what Fowles (1985) identifies as an emerging moral dimension to the work, though this might equally be described as a political dimension, which relates to private ownership, the abuse of the land by agribusiness and public use and access. This dimension is brought very clearly to the fore in Our Forbidden Land.

Margaret Drabble (2011), reviewing the exhibition Land Revisited, describes Our Forbidden Land as ‘an impassioned attack on the destruction of the countryside’. The introductory essay extends far beyond the landscape as addressed in earlier work, and includes critical analysis of nuclear power, transport policy, the military, climate, housing, pollution and the use of pesticides. These themes are reprised in the text that accompanies the images, which themselves are more clearly focused on the human abuse of the land, and play a role in making this abuse visible. An overarching theme is the alienation, and exclusion, of the public from the land, whether it be by the military, agribusiness, corporate ownership or heritage industry.

Today these issues are of even greater concern, and with respect to the access to the land that is available to photographers wishing to explore these environmental and social questions, Drabble observes:

‘Since her death in 2005, photographers have been finding their access to both public and private land more and more problematic, more expensive, and legally restricted. In Our Forbidden Land she wrote about the dilemma of access to Stonehenge, a site mass marketed by English Heritage which charges substantial sums to everybody, from individual artists to wealthy advertising companies. She foresaw a time when “the only photographs we are likely to see of the inner circles of Stonehenge will be those approved by English Heritage, generally by their anonymous public relations photographers”. Our common land would be the copyright of others’.

In my own exploration of community engagement with urban regeneration, I have assumed that I will progress from photographing the changing environment to an exploration of the lived experience of residents and other stakeholders. Engagement with Godwin’s photography and writing, and commentaries on this (in particular, the essay by Fowles), has led me to reassess this, and to consider how I might develop my urban environment image making further. Questions of access are even more pronounced with concerns around terrorism leading to suspicion of photographers in urban areas, and the private ownership of land by developers, with sophisticated surveillance technology, placing severe restrictions on where photographs can be taken. In assessing my own work and planning for the development of my project, I also want to consider how my work, one part of which has explored the meeting of the built and natural environment in urban settings, and the traces of human activity that are left in urban edgelands, has been visually influenced by Godwin’s images, and how I might develop this in urban settings over the coming months.

Whilst Godwin’s photography may not have a strong explicit conceptual basis, reinforced by her rejection of theory in preference to getting on with the work, her image making does have clear intent and is consistent and coherent in form. It can also be understood in relation to environmental art of the late twentieth century (for instance work by Richard Long and Andy Goldsworthy) in that the photographs engage with being in the landscape rather than being representations of the landscape. They are the products of walking across the land and being part of the landscape, rather than standing apart from the landscape. The work can also be understood in relation to forms of contemporary environmental activist art explored by Demos (2017). Godwin collaborated with environmental groups in the production of images, for instance with the Council for the Protection of Rural England concerned about the affect on the environment around Dover of the dumping of spoil in the construction of the Channel Tunnel. She eschewed the gallery system, preferring to publish books, and produced images and texts that demonstrated an understanding of day to day life in rural areas, whilst being clear about corporate and government sponsored action that threatens the environment, from nuclear power through to the manner in which English Heritage and the National Trust “have copyrighted our heritage” (quoted in Jeffery 2005), exemplifying her distinctly anti-authoritarian position and commitment to a critical role for photography.

References

Demos, T.J. 2017. Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Drabble, M. 2011. ‘Fay Godwin at the National Media Museum’. The Guardian. 8th January [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/jan/08/margaret-drabble-fay-godwin [accessed 30.12.18].

Fowles, J. 1985. ‘Essay’. In F. Godwin, Land, London: Heinemann: ix-xx.

Godwin, F. 1985. Land. London: Heinemann.

Godwin, F. 1990. Our Forbidden Land. London: Jonathan Cape.

Godwin, F. & R. Ingrams. 1980. Romney Marsh and the Royal Military Canal. London: Wildwood House.

Jeffrey, I. 1985. ‘Introduction’. In F. Godwin, Land. London: Heinemann: xxiii-xxix.

Jeffrey, I. 2005. ‘Fay Godwin: Photographic chronicler of our changing natural world’. The Guardian. 31st May [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2005/may/31/guardianobituaries.artsobituaries [accessed 30.12.18].

National Media Museum, Bradford. 2011. Fay Godwin: Land Revisited. Exhibition. 15 October 2010 – 27 March 2011 [online]. Available at: https://www.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/what-was-on/fay-godwin-land-revisited [accessed 30.12.18].

Sillitoe, A. & F. Godwin. 1983. The Saxon Shore Way: From Gravesend to Rye. London: Hutchinson.

South Bank Show. 1986. Fay Godwin. Season 10, Episode 6, 9th November [film]. Available at: https://youtu.be/4JE8I44Ak7o [accessed 30.12.18].