Royal Academy, 18th November 2019

Not primarily photography focused, but interesting in relation to my theme of community engagement with the arts. I accompanied a group of 50 Level 2 and 3 Art and Design students from Barking and Dagenham College on an evening visit to the Gormley exhibition. This included entry to the exhibition and a number of workshops exploring themes from the exhibition and from Gormley’s work more broadly.

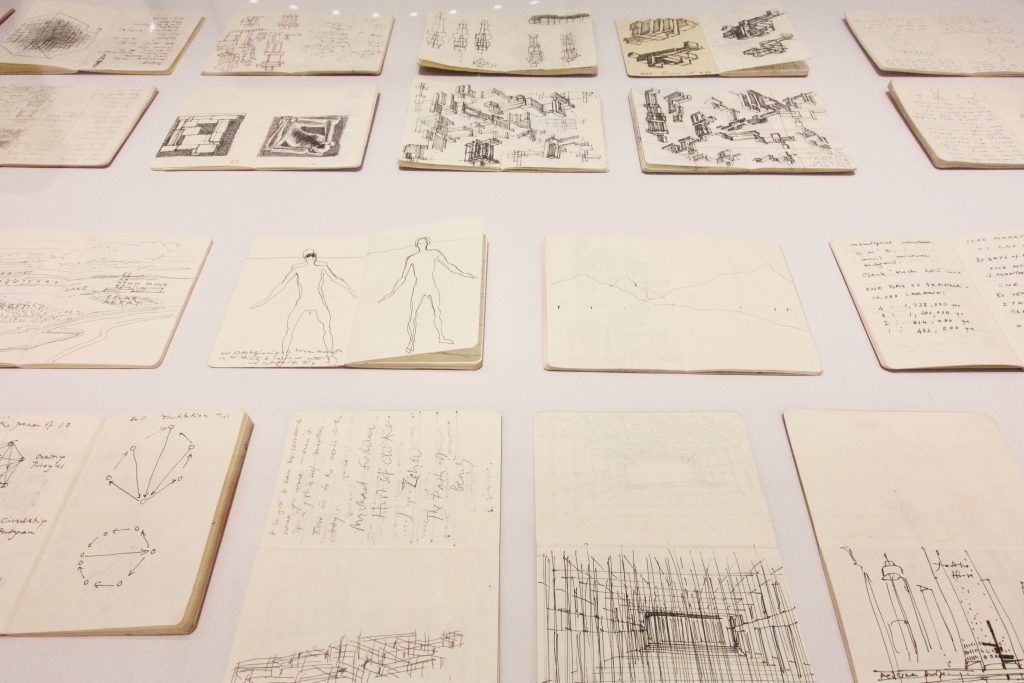

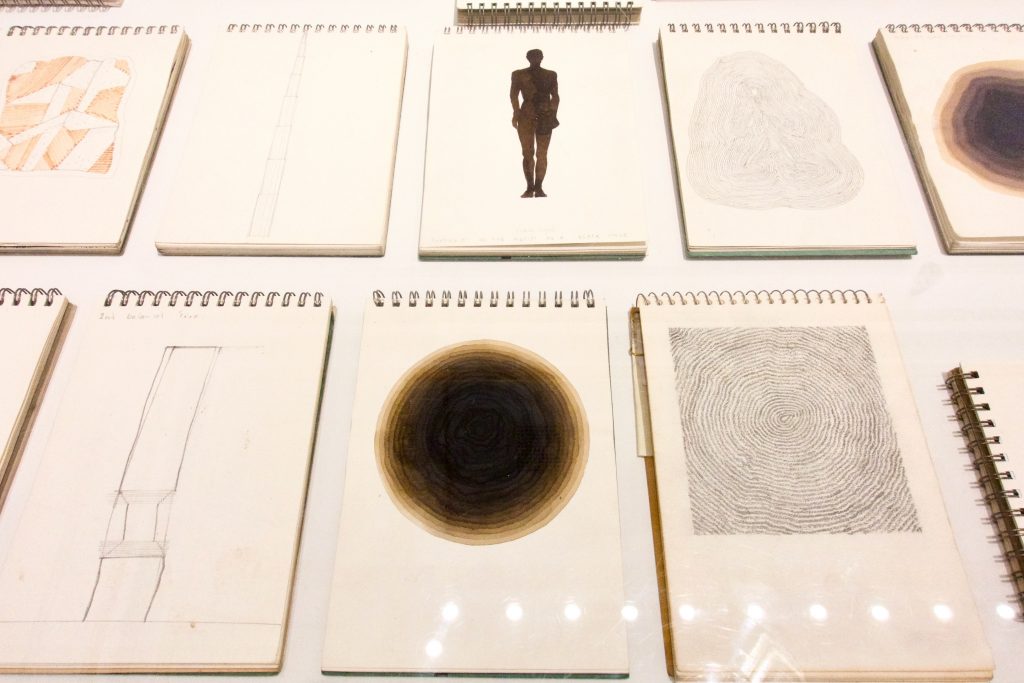

The exploration of the body in/as space/place relates to one aspect of my project. For Gormley, two dimensional work acts as a precursor to (but not studies for) his final three dimensional pieces. It was particularly interesting to see his sketchbooks, in which he has worked through and sketched out ideas for potential work (some of which is included in the exhibition).

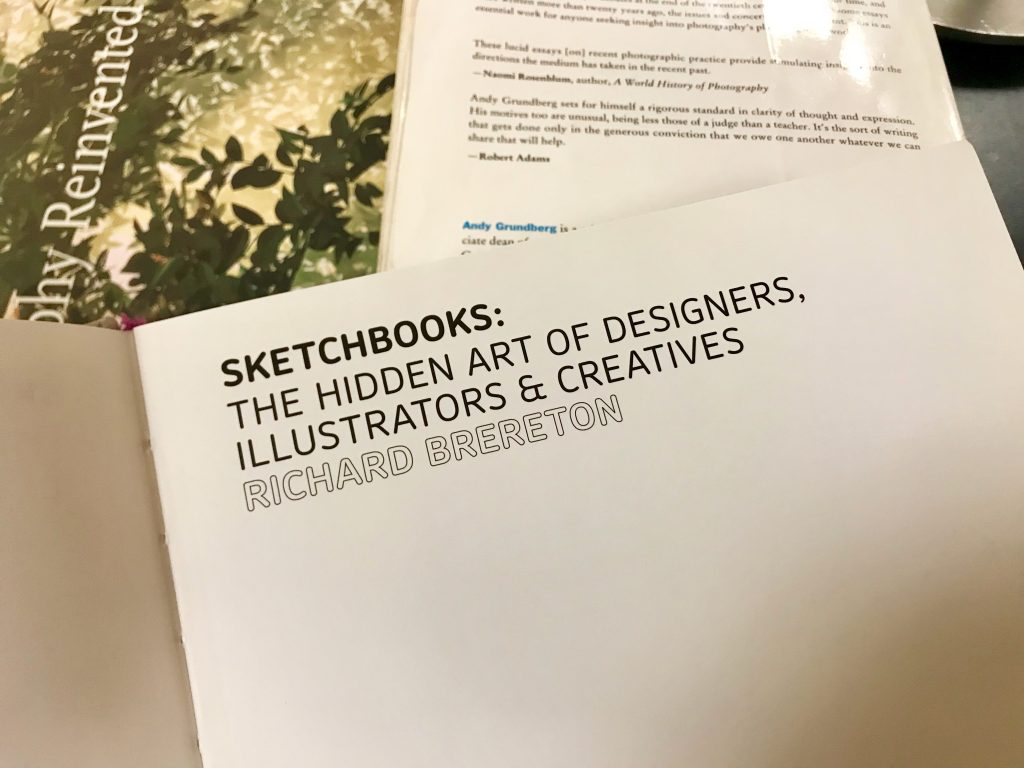

These are displayed as four chronological periods, and there are distinct differences in form and content over time. The most recent notebooks are more dense, and contain schematics for exhibitions as well as exploratory drawings and text for new works. My own exploratory work tends to be in the form of photographs, and my notebooks (I am keeping a notebook specifically for the FMP) are predominantly textual. I am coming from photography and writing to visual arts, and therefore drawing is not a foundational practice (as it is for others on the course, who have had a more conventional arts education). This prompts me to explore more visual forms of exploration and preparation for photograph work (for instance, in understanding what makes particular combinations of images work in the channel mixing process, and how I might plan the production of images more effectively for this process – important in using large format film. Weirdly, this is on the shelf next to me in the library as I write this.

A message to get more visual: my notebooks should become sketchbooks. In a conversation today, a photographer friend (who followed the conventional art school route) observed that I was using the MA as a kind of foundation course, which I suppose I am.

The workshops offered to the students were loosely structured and exploratory (using clay, exploring augmented reality, life drawing, making zines and 3D montages). The students were great, and really got involved, and seemed to enjoy the experience. It raised for me, though, the question about how to engage the public with art practice, in a way that gives greater access to the principles of production of artistic work (particularly important for those who, perhaps, don’t have the same degree of social and cultural capital as others who feel more at ease in these settings). The experience certainly seemed to make an institution like the RA more accessible. The scale of the education programme is remarkable, with workshops running every Monday and a target of 1000 participants per evening (it is sponsored by BNP Paribas, who cover the cost of transport and food, as well as the workshops). The group from the college that went on an earlier trip were fortunate to have a workshop run by Gormley himself.

Today I am exploring the possibility of exhibiting work and running a workshop at a local community arts and maker space. The challenge is to design the workshop in a way that engages participants in collaborative activity and also gives them confidence and agency as producers of artistic/photographic work, which requires a balance between guidance and autonomy, and a sharing of expertise.