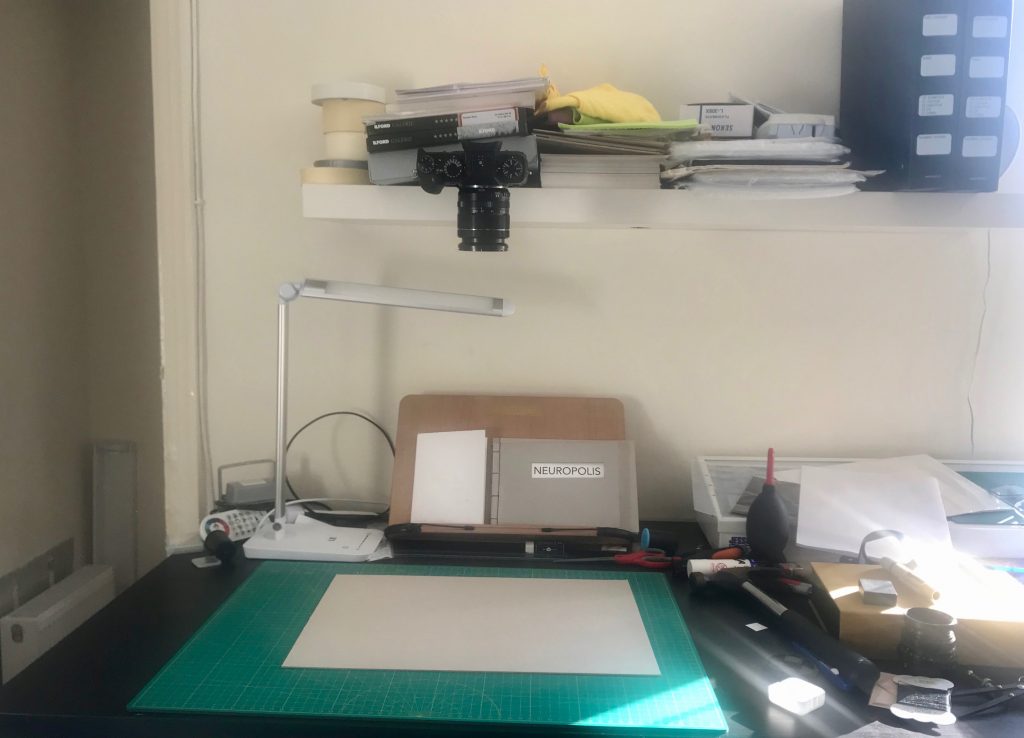

I’ve used the time over the break to explore practically the analogue and digital dimensions of the project, and how I can visually, and in terms of process, explore both the ‘datafication’ of decision-making in regeneration, and the transition from chemical/material production/distribution to digital/symbolic production/distribution in this part of east London (and, of course, the residue of the former lies alongside, and acts and is acted upon, by the latter (I’ll post a project statement that encapsulates this later). So moving back and forth between chemical processing, handmade bookmaking, coding and image manipulation (whilst initiating three new projects, starting the London Creative Network intensive artist development programme, and preparing for two pop-up exhibitions in the coming month, and all the ongoing work).

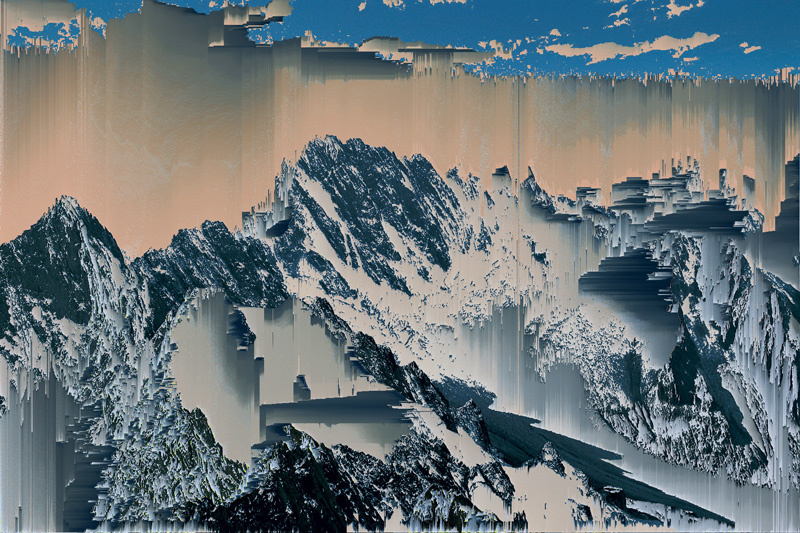

The algorithmic manipulation of images is a new strand, but important as it addresses part of the overall project that I have been struggling with (particularly finding a way to relate the quantification of community characteristics, and use of that data in decision-making on housing and social policy, and the lived, and located, experiences of residents). Using the Processing language (see Reas and Fry, 2007) to automate, through the use of algorithms, the manipulation of images is promising. To explore this, I have used Kim Asendorf’s pixel sorting (a term coined by Asendorf in 2010, according to Hight, 2013) code (available for download here; see examples of Asendorf’s work here and here).

At this point, I am playing around with changing the thresholds in the programme to produce different treatments of some of my landscapes and portraits, as well as some archival material. Here’s a version of the Barking Harbour image featured in an earlier post.

Each image is uploaded onto a surface as a bitmap and the procedure (sketch in Processing terms) runs along rows or columns (this can be set) to look for pixels in terms of darkness, lightness or brightness (this can be set). If set to search for ‘darkness’ along rows, the algorithm searches along each row for a pixel which lies within the thresholds set for ‘darkness’ and places these in order until it reaches a pixel that falls outside the defined limits. The number of iterations (loops) for this process can be set. The thresholds for each can be set to create different forms and levels of ‘mutilation’. This gives me an opportunity to contrast chemical degradation of images (using the immersion methods developed by Matthew Brandt) with these forms of digital degradation. I want to go beyond playful data-moshing, however, and see if I can feed in data (for instance, social progress indicator data) relating to the specific communities that I am working with.

This raises again the question of how to present the outcomes of the manipulation. My intention here is to continue to move back and forth between the digital and the analogue, and the abstracted and the located. So printing these could take us back into the analogue, local/located and visceral. As with all this work, the question is what is gained and lost in each translation between forms, if translation is possible, of course, in any meaningful sense (see Apter, 2013).

References

Apter, E. 2013. Against World Literature: On the politics of untranslatability. London: Verso.

Hight, J. 2013. An introduction to Kim Asendorf. Unlikely Stories, Episode IV. Online https://www.unlikelystories.org/13/asendorf0913.shtml [accessed 23.01.2020]

Reas, C and Fry, B. Processing: A programming handbook for visual designers and artists. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.