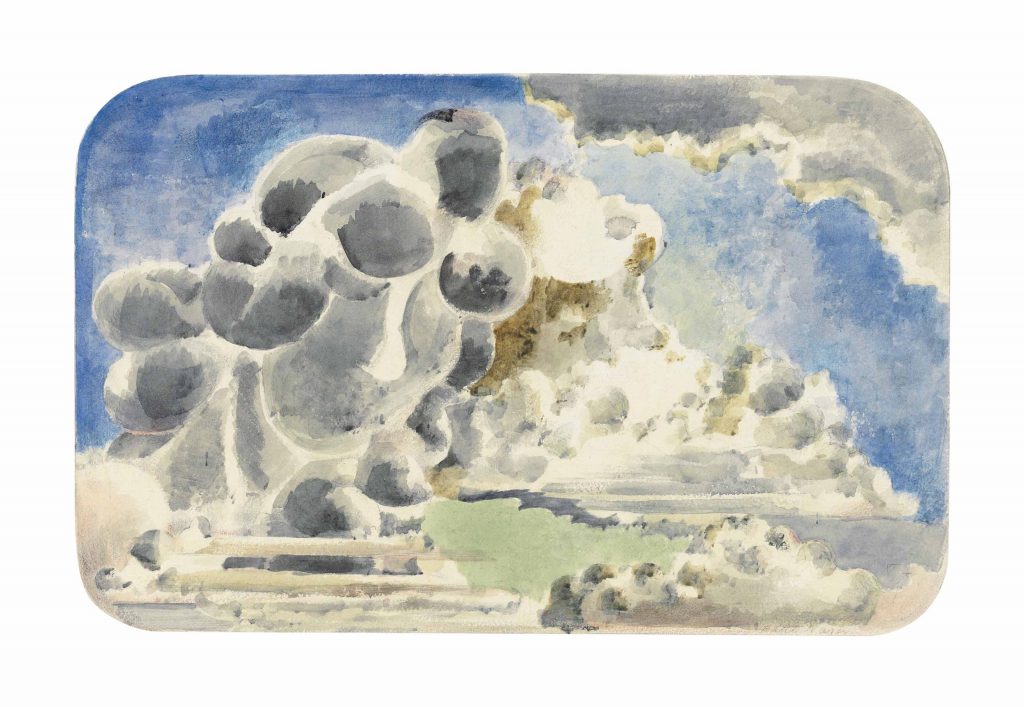

In the publication produced to accompany her three simultaneous London exhibitions in 2018, Landscape, Portrait, Still Life, Tacita Dean considers the extent to which Paul Nash’s watercolour Cumulus Head (c1944) can be considered to be a portrait (of Nash’s wife), a landscape (or more precisely, a cloudscape) and a still life (the head takes a sculptural form).

As such, the work questions, and subverts, the established distinction between landscape, portrait and still life. Dean’s three exhibitions focus in turn on each of these forms, but, as with Nash’s work, the permeability and instability of these forms, over time and across contexts, and the manner in which Dean’s work is positioned in respect these categories of work (and others working in these genres), raise further questions.

One question, which resonates with my own work, is the extent to which her landscape work tends to focus on the landscape, or on elements in the landscape. My own work tends to be very much in the landscape, tending to focus on objects and artefacts rather than the larger features of the landscape (as do many other so called landscape artists, like Fay Godwin, who’s photographs draw us to what is in the landscape, which prompt out attention to flicker between landscape as context and landscape as content: what is in the landscape provokes us to think differently about the landscape itself). This, in turn, raises a question about the category of still life, the defining feature of which appears to be the decontextualisation, or rather recontextualisation of the object (from, for instance, the field to the studio). Artists such as Andy Goldsworthy and Richard Long also question this distinction, creating works in and from the landscape.

This calls to mind the work of still life artists, such as John Crome, who work in the field, foregrounding particular aspects (for instance, Crome’s studies of flints, c1811, which, by focusing within the landscape, blurs the landscape/still life distinction).

The distinction is further problematised by the question of whether a still life has to be of inanimate, or dead, artefacts. Can living plants, or animals, or people, be the subjects of still life? Ultimately, the photograph renders them still, and animation can only be implied or inferred. New materialism, and object orientated ontology, of course, re-animate these objects and artefacts, in de-centring humanist accounts. This focuses us on consideration of how the landscape, human activity and objects inscribe and mark each other in the process of co-production, which I aim to explore in my own photographic work.

The composites produced for my neuropolis series can be seen as combining the landscape (urban), portraits (street) and still life (flora) in the same setting, with accompanying connotations of, in turn, a future, present and past. Whilst I have explored the interaction between these elements, I haven’t thought about the work in terms of artistic forms or genres. Dean’s exhibitions produce resonances between forms and each raises questions about stability and integrity of the boundaries between forms and genres. My work mashes these forms together and, in a modest way, raises similar questions in a different way. In addition, I hope, the use of composites and juxtapositions creates a possibility space for exploration of the potential of photography in inter-disciplinary enquiry and practice.

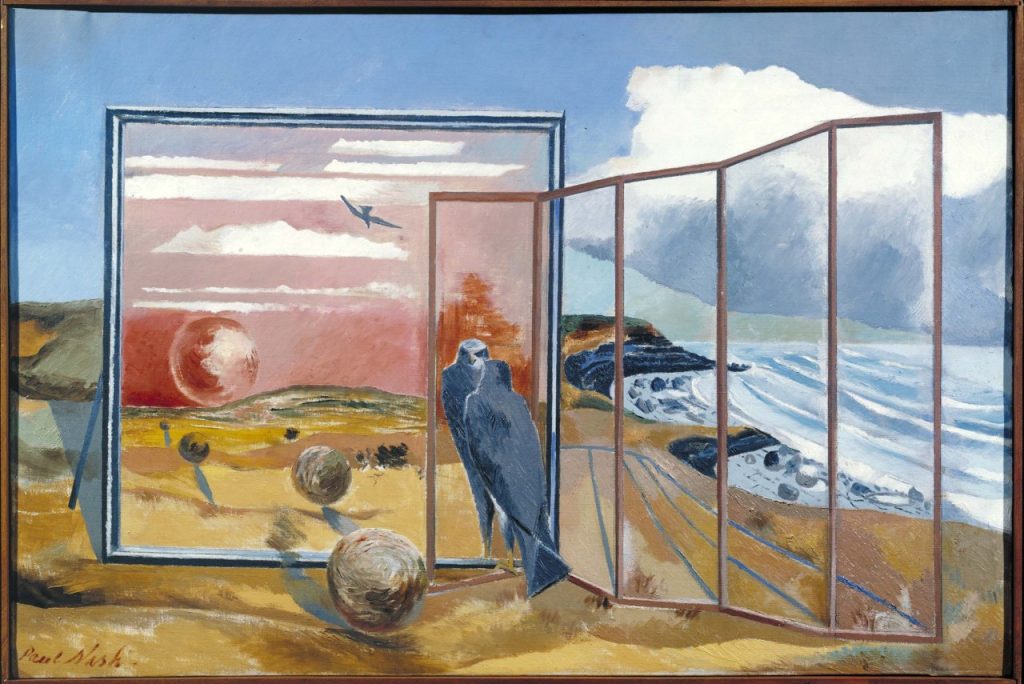

As a parenthetic thought, looking at Nash’s work in doing research for this post, there are other resonances with strands of my current work. In Landscape from a Dream (1938), for instance, Nash places frames and art works into the landscape, which is echoed in thoughts about exhibiting my work in non-gallery internal and external spaces, placing art work, and the structures that support it, in the landscape. I’ll follow this up in a future post.

His work held at the Imperial War Museum, for instance The Menin Road (1919), explores the manner in which war scars the landscape, in ways not dissimilar to the impact on the landscape of preparation for the large scale building development.

Interesting that entry to the AOP Student Awards 2020 has to be in one of three categories, people/places/things, that mirrors the long established, but clearly questionable, portraits/landscape/still life distinction considered here.

References

Harris, A., Hollinghurst, A. & Smith, A. 2018. Tacita Dean: Landscape, Portrait, Still Life. London: Royal Academy of Arts.