Looking forward to starting the programme in January, with mentoring from Kathrin Böhm & Levin Haegele.

Doctorate in Fine Art and MA in Photography Critical Research Journal

Looking forward to starting the programme in January, with mentoring from Kathrin Böhm & Levin Haegele.

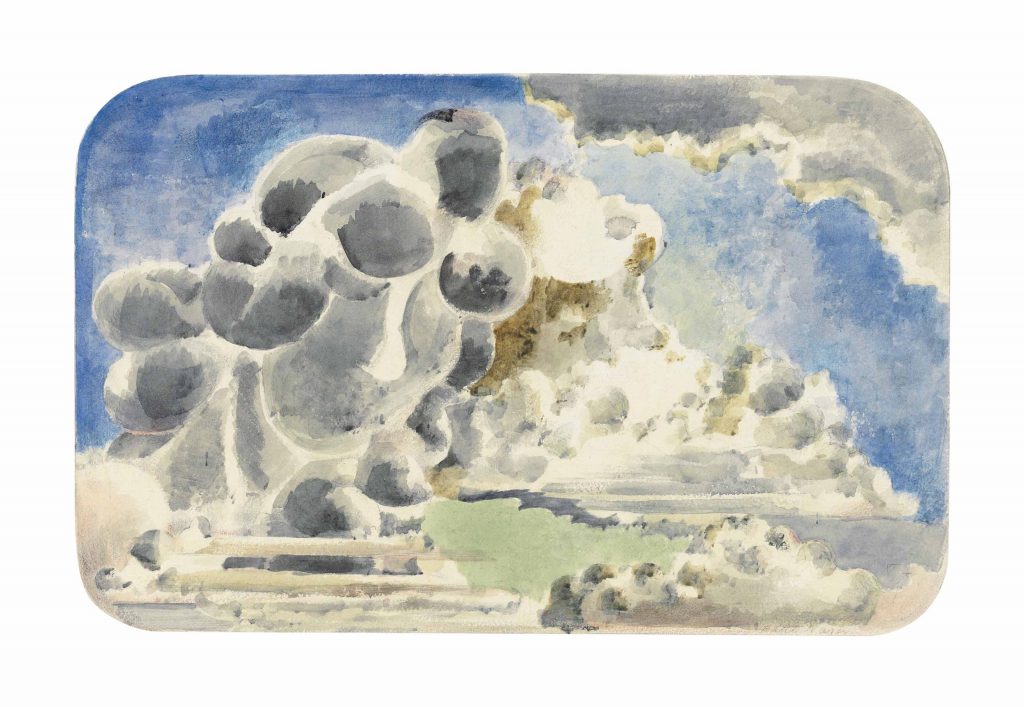

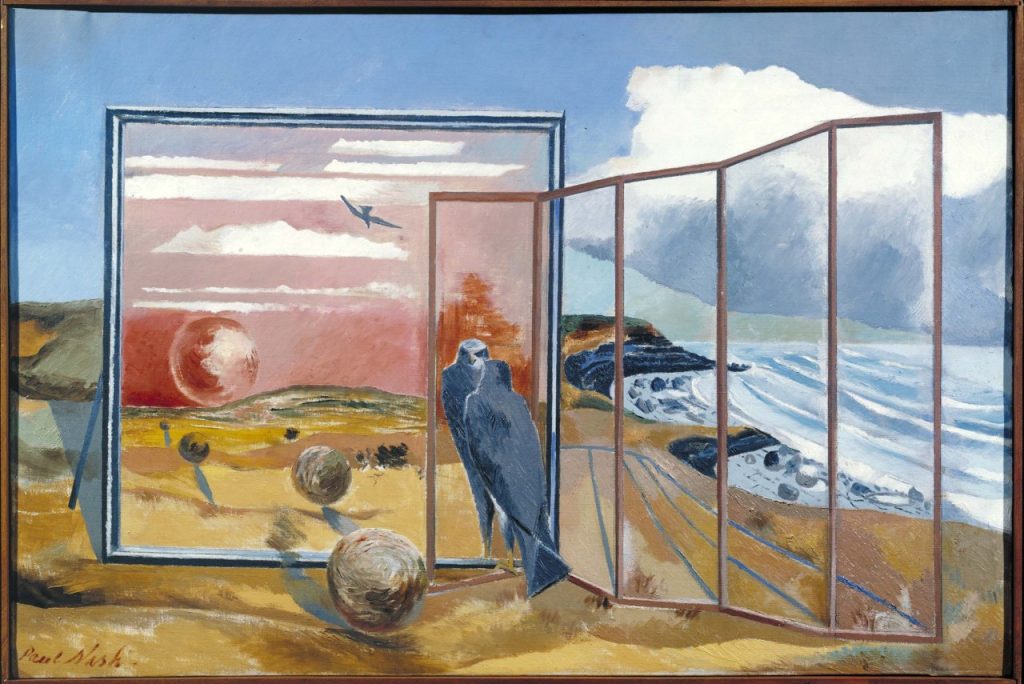

In the publication produced to accompany her three simultaneous London exhibitions in 2018, Landscape, Portrait, Still Life, Tacita Dean considers the extent to which Paul Nash’s watercolour Cumulus Head (c1944) can be considered to be a portrait (of Nash’s wife), a landscape (or more precisely, a cloudscape) and a still life (the head takes a sculptural form).

As such, the work questions, and subverts, the established distinction between landscape, portrait and still life. Dean’s three exhibitions focus in turn on each of these forms, but, as with Nash’s work, the permeability and instability of these forms, over time and across contexts, and the manner in which Dean’s work is positioned in respect these categories of work (and others working in these genres), raise further questions.

One question, which resonates with my own work, is the extent to which her landscape work tends to focus on the landscape, or on elements in the landscape. My own work tends to be very much in the landscape, tending to focus on objects and artefacts rather than the larger features of the landscape (as do many other so called landscape artists, like Fay Godwin, who’s photographs draw us to what is in the landscape, which prompt out attention to flicker between landscape as context and landscape as content: what is in the landscape provokes us to think differently about the landscape itself). This, in turn, raises a question about the category of still life, the defining feature of which appears to be the decontextualisation, or rather recontextualisation of the object (from, for instance, the field to the studio). Artists such as Andy Goldsworthy and Richard Long also question this distinction, creating works in and from the landscape.

This calls to mind the work of still life artists, such as John Crome, who work in the field, foregrounding particular aspects (for instance, Crome’s studies of flints, c1811, which, by focusing within the landscape, blurs the landscape/still life distinction).

The distinction is further problematised by the question of whether a still life has to be of inanimate, or dead, artefacts. Can living plants, or animals, or people, be the subjects of still life? Ultimately, the photograph renders them still, and animation can only be implied or inferred. New materialism, and object orientated ontology, of course, re-animate these objects and artefacts, in de-centring humanist accounts. This focuses us on consideration of how the landscape, human activity and objects inscribe and mark each other in the process of co-production, which I aim to explore in my own photographic work.

The composites produced for my neuropolis series can be seen as combining the landscape (urban), portraits (street) and still life (flora) in the same setting, with accompanying connotations of, in turn, a future, present and past. Whilst I have explored the interaction between these elements, I haven’t thought about the work in terms of artistic forms or genres. Dean’s exhibitions produce resonances between forms and each raises questions about stability and integrity of the boundaries between forms and genres. My work mashes these forms together and, in a modest way, raises similar questions in a different way. In addition, I hope, the use of composites and juxtapositions creates a possibility space for exploration of the potential of photography in inter-disciplinary enquiry and practice.

As a parenthetic thought, looking at Nash’s work in doing research for this post, there are other resonances with strands of my current work. In Landscape from a Dream (1938), for instance, Nash places frames and art works into the landscape, which is echoed in thoughts about exhibiting my work in non-gallery internal and external spaces, placing art work, and the structures that support it, in the landscape. I’ll follow this up in a future post.

His work held at the Imperial War Museum, for instance The Menin Road (1919), explores the manner in which war scars the landscape, in ways not dissimilar to the impact on the landscape of preparation for the large scale building development.

Interesting that entry to the AOP Student Awards 2020 has to be in one of three categories, people/places/things, that mirrors the long established, but clearly questionable, portraits/landscape/still life distinction considered here.

References

Harris, A., Hollinghurst, A. & Smith, A. 2018. Tacita Dean: Landscape, Portrait, Still Life. London: Royal Academy of Arts.

I’m preparing work for two pop-up exhibitions over the coming two weeks: (i) images from the Creekmouth project with 7-11 year olds over the summer to accompany a public viewing of the film made with NewView Arts and funded by the Arts Council: (ii) images from the English courses being run for parents at Riverside Campus and for residents at Sue Bramley Centre. As with the earlier Shed Life pop-up, I am printing and mounting photographs and figuring out how to exhibit them in the space available in a way that is quick to assemble and low impact on the space. At the end of the Shed Life event, I gave most of the photographs away to people who took part, and it’s likely that I’ll do the same for these events.

Longer term, though, and in relation to the outcomes of the FMP, I need to think about developing a way of displaying my work which is both durable and portable. Using an archive box has enabled me to carry and show the work I am doing in an intimate manner, and it might be fruitful to develop this further for material that can be displayed.

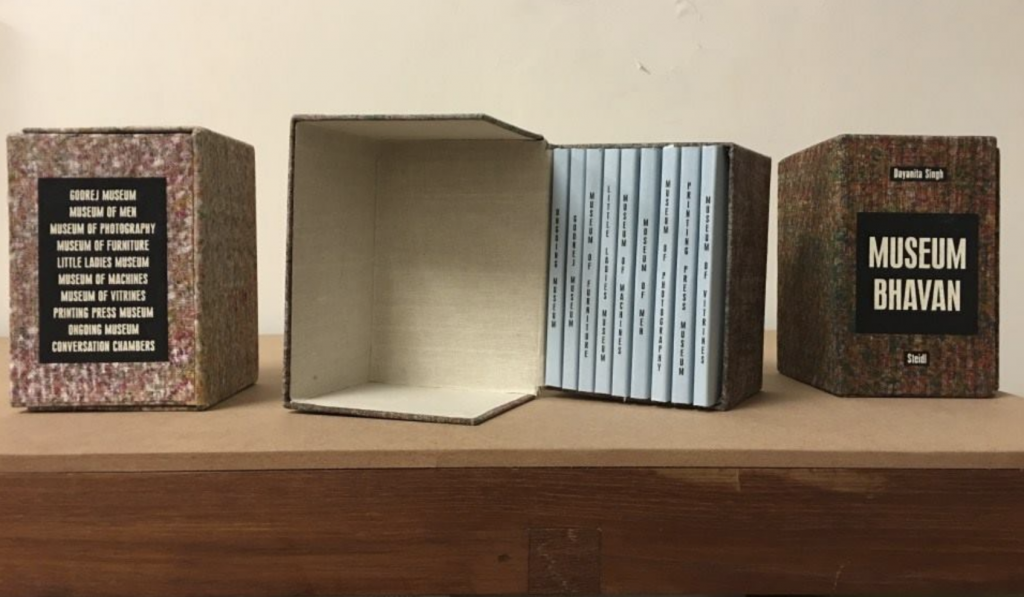

This idea of portability and adaptability is at the heart of Dayanita Singh’s work, and in particular her book objects. For instance, her Box 507, which she describes as follows:

‘an unbound book of 30 image cards held together in a wooden structure. It is meant to be hung on a wall or placed as an object on a table. The structure has been built to allow the collector to change the front image as often as they like. The image cards, however, exist as a set of 30 and are not meant to be separated from each other or the box. Once you have more than one box, you become the curator of my work, as you build your own conversations between the boxes. Box 507 has been published in an edition of 360 and is available only in its exhibition format. It is to be acquired directly off the wall. In this way the exhibition disappears with time and when all the boxes are sold, the edition and exhibition are over.’

The work thus consists of both the images and the casing, which allows the images to be transported and exhibited in different ways in different spaces. Museum Bhavan takes this a step further in presenting a number of ‘museums’ as a set of books, allowing the reader to construct different configurations of the work.

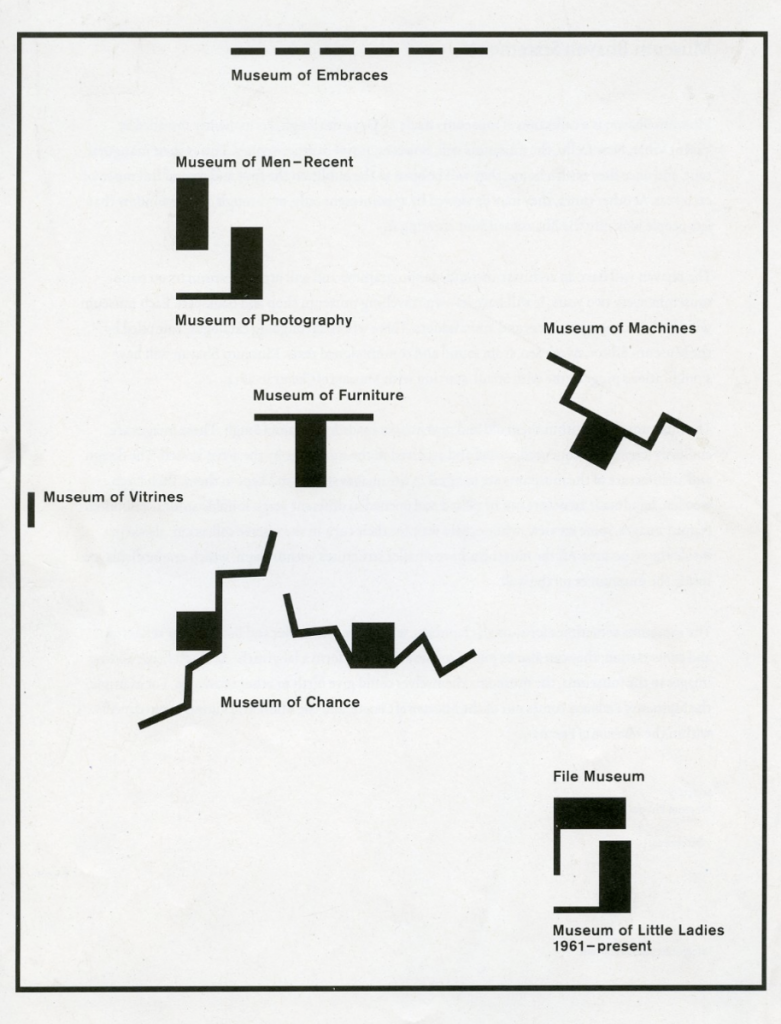

This ‘pocket museum’ mirrors Singh’s traveling exhibition, which can be configured in different ways in different galleries. The plan below is the scheme for her Haywood Gallery exhibition.

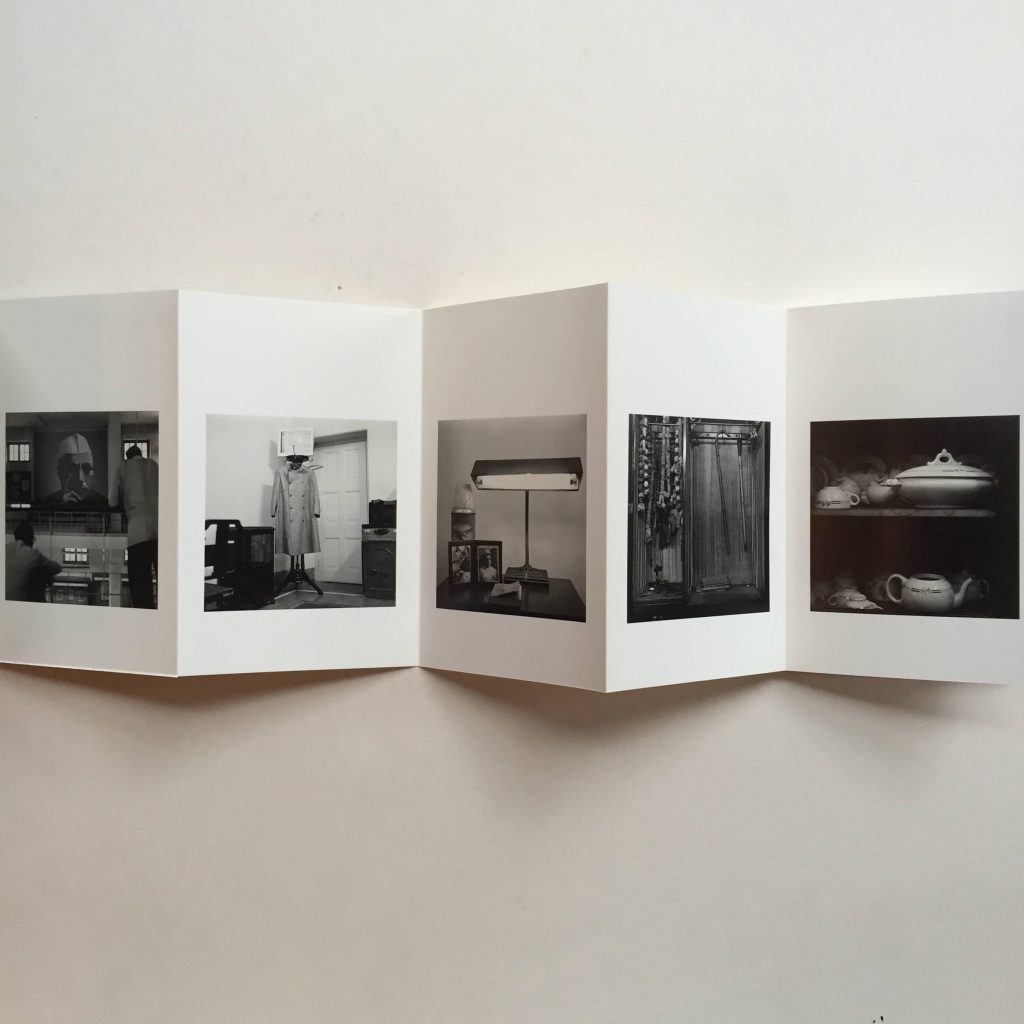

Accordion-fold books are also used as a way of displaying work, which I will explore with the work that I have been doing with Thames Wards Community Project (better, I think, than zine format as it provides a more satisfying object and allows the work to be displayed).

Looking at other forms of low-cost but flexible forms of display, the Gerrit Rietveld Academie exhibit at Unseen Amsterdam this year is interesting.

Their Uncut 2019 group exhibition provides another option (using photostands for the suspension of large prints).

References

Dayanita Singh, http://dayanitasingh.net

Great to see SPACE Ilford open this weekend. Provided the opportunity to visit the new studios and talk to the artists who have moved in so far. Not much in the way of photography, but some interesting digital media work, with a number of artists in residence working on new projects.

Spoke to people from the London Creative Network (LCN) and have subsequently put in an application for their artist development programme – see statement below. A great opportunity to make links with other local artists and work on development of my practice beyond the MA. Putting the application together provided an opportunity to think about how I frame my current practice and how I might develop my work over the coming years.

Statement

I am a photographic artist, writer, academic and educator exploring the ways in which photography can make a distinctive contribution to inter and multi-disciplinary practice and enquiry. My current work focuses on community engagement with urban regeneration in the outer east London boroughs, through exploration of the entanglement of human activity with the changing built and natural environment. This involves three forms of photography: working with residents’ own images to explore and understand their lived experiences and aspirations, collaborative image-making with community and activist groups for use in advocacy, and my own artistic exploration stemming from a range of local community projects. My practice is post-digital, and I produce images and artefacts using digital, analogue and alternative processes, exploring what is added and subtracted as we move between different forms of production and circulation. This resonates with the increasing quantification of human experience and data driven decision-making (in housing development and employment) and the environmental consequences of the change over time from chemical to digital industries in east London. To date this work has been disseminated through community pop-up exhibitions and group shows, and contributions to publications and archives (for instance, relating to a recent fire on a local estate).

Benefit

Following a career in education, I have returned to an earlier interest in photography (which began at the age of four as a child model). I will shortly complete an MA in Photography. My artistic work is currently subsidised by other forms of income. The LCN programme will help me transition to a primary focus on artistic work, and enable me to develop a financially, ethically and artistically sustainable plan for developing my practice.

I have lived in Ilford for the past 20 years. I am committed to development of the community, and have, for instance, served as a governor of local schools and colleges. I am excited about the developments at SPACE and potential for the arts to play a part in the revitalisation of the town and borough. My current work focuses on estates in Barking: having seen how developers exploit artistic work and that arts funding often fails to engage residents meaningfully, I am interested in developing alternative funding models for community focused art.

My primary motivation is to learn. I also hope that my experience and expertise can benefit others in the network, at a time when inter-generational understanding and collaboration is vitally important.

https://www.lensculture.com/submission-reviews/73881

LensCulture-AB-submission-reviewI’m not sure about the standing of these reviews, but it seemed like a good idea to get feedback on the composite work from as many perspectives as possible. I submitted five images from the neuropolis series. The review draws attention to the need to attend to formal compositional aspects of each image, which I need to do in disentangling what kinds of combinations of images work best. The issue raised about the different degrees of spatial depth in the images is interesting, and something I need to consider in future composite image making. Most of all, it is pleasing that the reviewer thinks that it would be worthwhile to consider projection of the images, and finding ways in which the viewer might be able to move through and interact with the images in an exhibition space. This is something I have started to explore, and the review has motivated me to go further with this. Overall, a positive and constructive review, which has encouraged me to explore formal composition in a more focused way, and work out how I could project the images effectively.

The purpose of the tutorial was to take stock and set a clear direction for production of the FMP outcomes. Whilst the individual projects are moving forward, I want to allow them to take their own course (with their own timescales) and to view them as a resource for my over-riding (clearly defined) FMP project, which by necessity has to be completed by May 2020. The diversity and complexity of the projects provides a rich set of possibilities in terms of the focus for the project. The challenge at this point in time is to clearly define the direction and outcomes of the project.

We discussed possible over-arching themes for the FMP project. The relationship between the natural and built environment and human activity (and, in particular, the ‘pushing back’ of the natural environment against human exploitation) appears to have most potential (for instance, in relation to the history of flooding of the marshland on which the Thames View, Thames Reach and Riverside estates are built, the recent fire on Riverside, the destruction of trees on the Gascoigne Estate, the pollution of land in the area by the coal-fired power station and other industrial units and so forth). This can be addressed through collaboration with selected participants in the micro-projects, and will involve archival work, environmental portraits, quotations, sound recordings, personal and official documents, photographs of the natural and built environment and of human activity relating to the place, developer and other images of current and future building, including CGIs. The work could focus on something like eight themes spanning both inter-twined environmental and human concerns (for instance, flood, fire, infestation, environment damage, mental health, migration, communication, isolation). Each theme could have a collaborator/informant, and would include material relating to their life world, trajectory and aspirations. The work could be presented as a multi-modal installation (see earlier discussion of the work of Edmund Clark and Janet Lawrence, for instance). The aim would be to invoke a sense of the relationships being explored, not a literal description. For that reason, and because of the complexity of the relationships, the exhibition (or other output) would not be explicitly themed (which raises the question of how to organise the work – do, for instance, I cluster the the biographical and archival material around the related composite image, what text is used and how, what is the relative scale of the images, and so on).

Specific issues raised in the tutorial:

Thames Ward Community Project, Barking, 25th November 2019.

Workshop with members of the TWCP Citizen Action Group, exploring ways of constructing compelling stories to coney a sense of the work that people are doing in the community. We worked with a template based on Joseph Campbell’s universal story structure (from ‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces’).

Our initial exercise was to work through the section of the template with our own community activist story as a focus. For me, this illuminated the manner in which I have used similar narrative structures to construct my own biographical accounts (see forthcoming post on Andreas Gursky’s photographic biography). It also reinforced my commitment to evade and subvert the common desire for photographic storytelling in my work (see reflection of Week 10 Tutorial for exploration of the implications of this for the outcomes of my FMP). Quite how image making fits with this is an open question. Film was used to illustrate how the structure drives narrative and moves to resolution (key in the use of stories to persuade). Images could be used to illustrate the unfolding of the narrative but this literal and descriptive approach would limit the use of images to adornment. As the members of the group produce narratives around their own work, it is an interesting challenge to produce images to supplement and enhance these.

For the second part of the session, we worked in pairs to create narrative for people who had been identified as ‘villains’ in our own narratives (the council, the developer, funders), a useful exercise in decanting, the principle point being that people do see themselves as the villains in their own stories, so to be convincing, we have to appreciate, and incorporate, these narratives into our own. Again, this issues a challenge to image making.

The workshop was useful not only in exploring the use of stories in advocacy, and clarifying our own stories, but also in the illumination of each others motivations and aspirations, which for me creates a stronger base from which to develop my photographic work in this context.

Resources

Campbell, J. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. 1st edition, Bollingen Foundation, 1949. 2nd edition, Princeton University Press. 3rd edition, New World Library, 2008

Stronger Stories, Resources https://strongerstories.org/resources#resources

Royal Academy, 18th November 2019

Not primarily photography focused, but interesting in relation to my theme of community engagement with the arts. I accompanied a group of 50 Level 2 and 3 Art and Design students from Barking and Dagenham College on an evening visit to the Gormley exhibition. This included entry to the exhibition and a number of workshops exploring themes from the exhibition and from Gormley’s work more broadly.

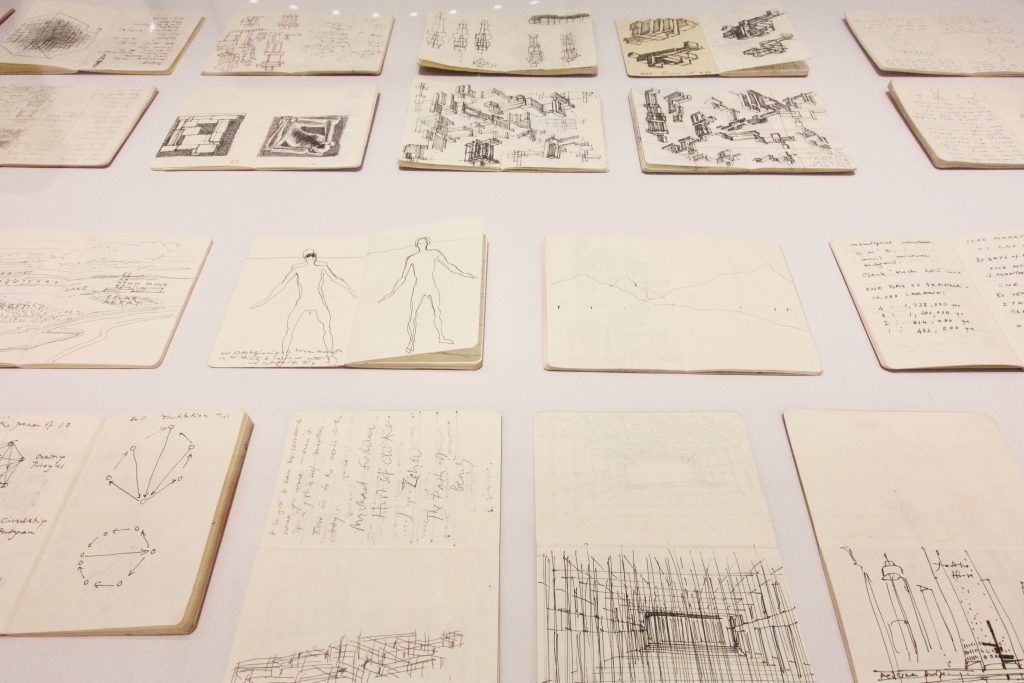

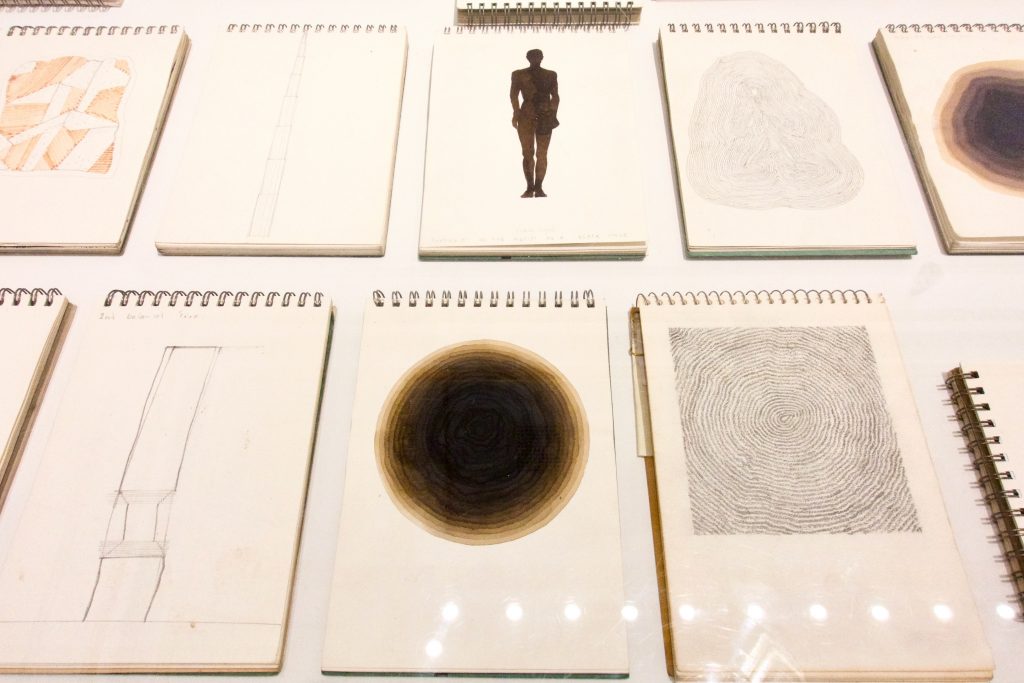

The exploration of the body in/as space/place relates to one aspect of my project. For Gormley, two dimensional work acts as a precursor to (but not studies for) his final three dimensional pieces. It was particularly interesting to see his sketchbooks, in which he has worked through and sketched out ideas for potential work (some of which is included in the exhibition).

These are displayed as four chronological periods, and there are distinct differences in form and content over time. The most recent notebooks are more dense, and contain schematics for exhibitions as well as exploratory drawings and text for new works. My own exploratory work tends to be in the form of photographs, and my notebooks (I am keeping a notebook specifically for the FMP) are predominantly textual. I am coming from photography and writing to visual arts, and therefore drawing is not a foundational practice (as it is for others on the course, who have had a more conventional arts education). This prompts me to explore more visual forms of exploration and preparation for photograph work (for instance, in understanding what makes particular combinations of images work in the channel mixing process, and how I might plan the production of images more effectively for this process – important in using large format film. Weirdly, this is on the shelf next to me in the library as I write this.

A message to get more visual: my notebooks should become sketchbooks. In a conversation today, a photographer friend (who followed the conventional art school route) observed that I was using the MA as a kind of foundation course, which I suppose I am.

The workshops offered to the students were loosely structured and exploratory (using clay, exploring augmented reality, life drawing, making zines and 3D montages). The students were great, and really got involved, and seemed to enjoy the experience. It raised for me, though, the question about how to engage the public with art practice, in a way that gives greater access to the principles of production of artistic work (particularly important for those who, perhaps, don’t have the same degree of social and cultural capital as others who feel more at ease in these settings). The experience certainly seemed to make an institution like the RA more accessible. The scale of the education programme is remarkable, with workshops running every Monday and a target of 1000 participants per evening (it is sponsored by BNP Paribas, who cover the cost of transport and food, as well as the workshops). The group from the college that went on an earlier trip were fortunate to have a workshop run by Gormley himself.

Today I am exploring the possibility of exhibiting work and running a workshop at a local community arts and maker space. The challenge is to design the workshop in a way that engages participants in collaborative activity and also gives them confidence and agency as producers of artistic/photographic work, which requires a balance between guidance and autonomy, and a sharing of expertise.

UCL Institute of Making, 19th November 2019

‘The path of least resistance leads to elegant solutions’ Brian Eno, Oblique Strategies.

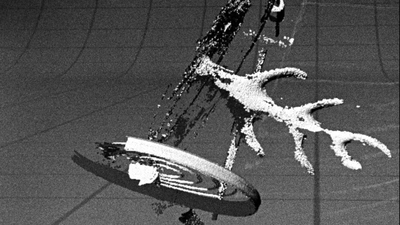

Seminar with Frances Scott, and showing/discussion of her film PHX [X is for Xylonite]. The film is the outcome of a collaborative project between UCL and Bow Arts focussing on plastics in the industrial heritage of the River Lea area. There was also an exhibition at the Nunnery Gallery and a publication (Vickers and Hill, 2019). The project provides a good example of a multi-disciplinary exploration of a theme (in this case plastics), spanning the arts, sciences and social sciences. It also focuses on a specific area of east London and explores the industrial history of the area around Hackney Wick (which includes buildings, now demolished, that I photographed in the first module). Frances works with a Bolex hand cranked camera and 100 ft reels of 16mm film, which she bucket processes. The use of film here is apposite as Xylonite (Ilford bought Xylonite for the process) came to be rebranded as celluloid, the material base for film. The film incorporates archival material and accounts. Objects from collections are incorporated by 3D laser scanning (fast scanning leads to degraded object images, mirroring the decaying of early plastic objects) and photogrammetry. The work is created by a process of ‘stitching together’. Frances tends to ‘let the material determine the process’.

Local people were involved in the steering group, and visits to archives and local sites were organised. Polymer chemists and other experts were involved in the process. An exhibition was organised around museum objects and artistic responses to these by Slade students.

References

Vickers, N. and Hill, S. (eds) 2019. Raw Materials: Plastics (Exploring the industrial heritage of the River Lea through a series of materials). London: Bow Arts.

RPS, Bristol, 16th November 2019

Very fortunate to have a tour of the exhibition with Curator Mark Rawlinson and then attend a panel discussion with Jack Latham, Erla Bolladóttir and Gísli Guðjónsson as part of the Falmouth MA meet-up in Bristol. There are a number of issues raised by the exhibition and discussion that are important for my own project.

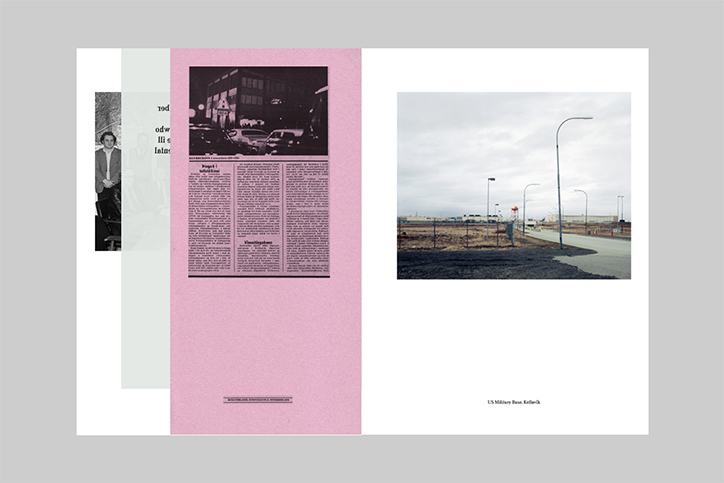

The first relates to the relationship between Latham’s photographs, archival (including police) photographs, texts and artefacts. These are combined to suggest not just that that there are multiple conflicting accounts, but that accounts (and the place of photography in relation to these) are contingent, uncertain and unstable. Whilst some of Latham’s photographs revisit earlier archival images, they do not remake, or rephotograph, places and scenes, but rather revisit and re-present the place. In some cases, the places have undergone dramatic change, in other cases images of the people, and things, that now populate the landscape are presented. Images are presented out of sequence and in different forms and formats, to disorientate and disrupt in the manner of the forms of interrogation utilised. The materials provide a resource for, but don’t dictate, the construction of narratives. As Latham stated in discussion, he wants to thwart our tendency to ‘bend images to fit narratives’. Alongside each other the different forms of material prompt us to raise questions, rather than constitute a single narrative or an unambiguous description. In my own project I have to think carefully about the relationship between different elements, and the complex relationships between people, places, things and different accounts.

The second relates to the relationship between the different realisations of the project. The exhibition and the book are clearly very different ways of engaging with the work (and the discussion between the photographer and other participants in the project is yet another). Moving around the gallery makes the investigation of the narratives easier than the linear structure of the book. The scale of of the photographs and the juxtaposition in space are also to the fore in the gallery space (pictures are in clusters, next to each other, opposite each other, obscured and revealed by movement around the space. On the other hand, the book offers a tactile experience, accentuated by the use of different papers (including sugar-paper), gatefolds and french folds, loose images, text on transparent papers and so on. This mirrors my earlier discussion of the the relationship between film Island and the related installation.

The third aspect relates to the relationship between the photographer and the participants in the project (also raised in the guest lecture by Sebastian Bruno this week, who initially made his work with minimal engagement with the community, but latterly has adopted a more collaborative approach). The project required close collaboration with the people imprisoned and those involved in seeking justice. Latham mentioned that he sought the agreement of the people involved before the final edit of the book was approved (he arranged to have a meal with everyone and went through the edit with them). This emphasised the importance of engaging collaborators in deciding the form that are taken by the outcomes of the project.

The fourth relates to consideration of what it is possible for photography to achieve, and how it might contribute to a multi-disciplinary investigation (such as this project, which involves psychologists, forensic investigators, ‘conspiracy theorists’ and others). Latham is clear about the limitations of photography to tell stories, and raises questions, for me, about whether ‘telling stories’ should be a primary aspiration for photographers. Rawlinson refers to Allan Sekula’s advocacy of the use of sequences of photographs through which to create a narrative. Latham’s work operates in a different way. His aesthetically and technically accomplished images are woven into the other material to produce multiple narratives. Their contribution is distinct, and arguably could not have been achieved by any other form expression/(re)presentation. The images alone do not form a narrative, nor do they provide, in themselves, illumination or analysis. They do, though, draw us into engagement with the people and places depicted, and their part in the overall complex of narratives. They also disrupt assumptions about placed he passage of time. The success of this, for me, has its foundations in Latham’s modesty about what photography alone can achieve, and inquisitiveness about how these achievements can be enhanced within a multi-disciplinary, and multi-modal, project. This is at the heart of my own project, which seeks to explore what, distinctively, photography can contribute, both as a practice and outcomes, in multi- and inter-disciplinary work.