‘The growing together of parts originally separate’ (OED).

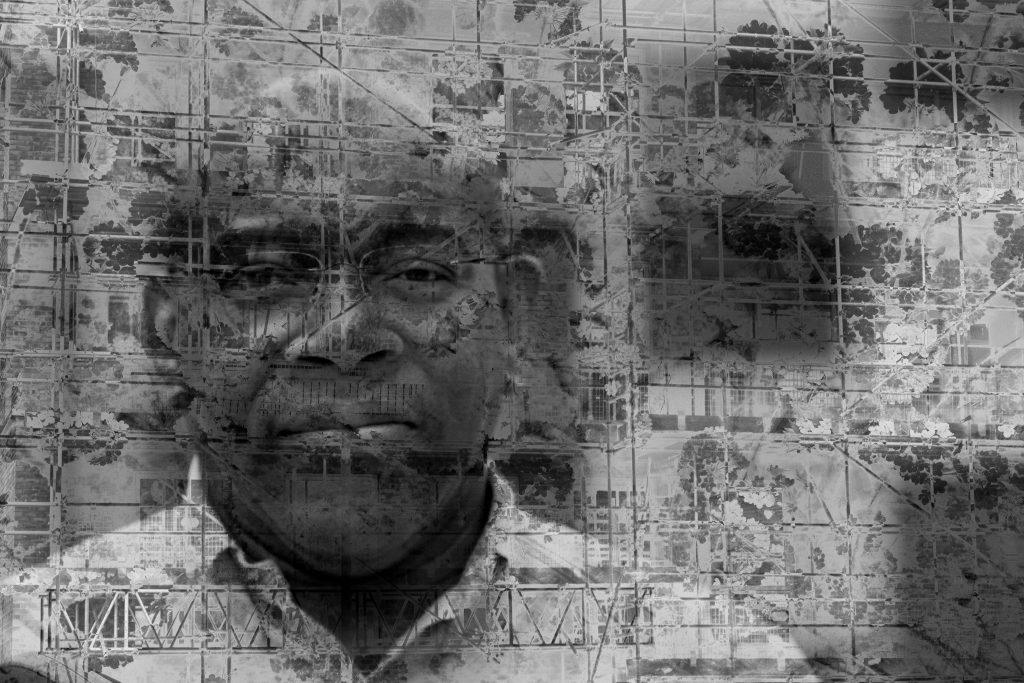

In the early stages of the FMP a key issue for me has been the relationship between the various ‘micro-projects’ and the FMP outcomes. Whilst leaving this to emerge over the coming months has particular creative benefits (for instance, in the exploration of the entanglement and entwinement of themes both in the process and outcomes of the project), the uncertainty around what will be produced and how it will be publicly disseminated is unsettling (and potentially might lead to non-completion). Reflecting on progress to date with the FMP, I am now thinking of reformulating the relationship between the ‘micro-projects’ and the FMP outcomes. Over the past few weeks, the individual projects have developed at different speeds and with different visual, and other, outcomes. This makes anticipation of the final form of the FMP challenging. One way to mitigate the risks is to develop a ‘meta-project’, with its own distinct focus and outcomes, but which can draw on the processes and outcomes of the ‘micro-projects’. In this way, the FMP project can benefit from progress with the projects, but is not directly dependent on them. I’ll formulate a precise statement of the objectives of the project in a later post. Over this week I have been exploring possible exhibition spaces and thinking about how the project could be framed to produce outcomes that would be appropriate in these spaces.

One possibility is the small pop-up gallery in a vacant shop at Barking Station. This is run by Barking Enterprise Centre, and features the work of local artists (as a succession of single artist exhibitions).

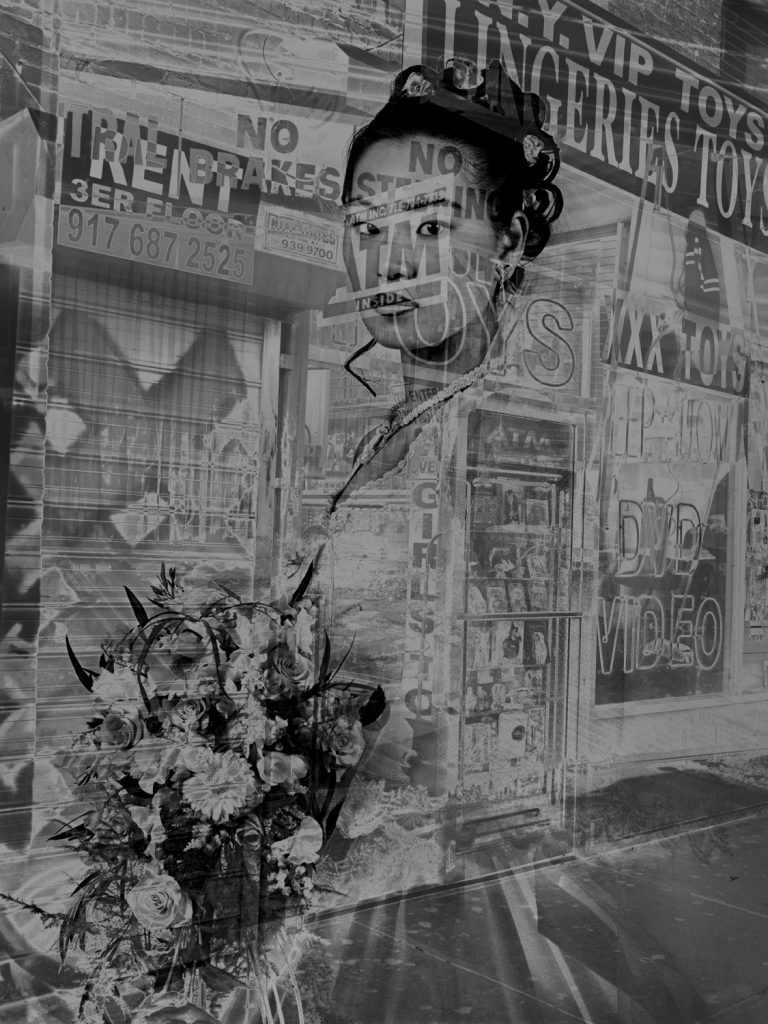

The space is flexible with good natural light and, given the location, very high footfall. The current exhibition features the work of local artist Griffi.

Another possibility is the Warehouse, one of the Participatory City sites. This is a large and very flexible space which has the advantage of allowing workshops to be run alongside (and/or as a precursor and/or follow-up to) the exhibition.

A third option might be the Studio 3 Arts space in Vicarage Fields Shopping Centre, where I have had work exhibited as part of the 2019 Barking Arts Trail, though space is limited here.

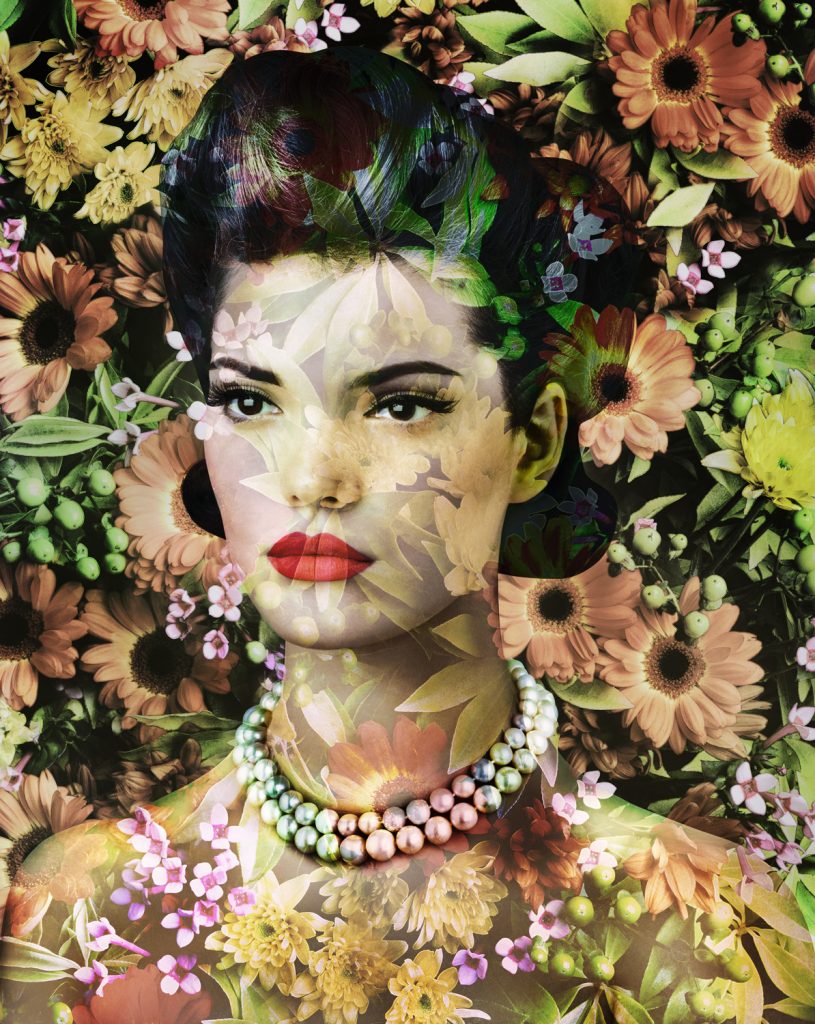

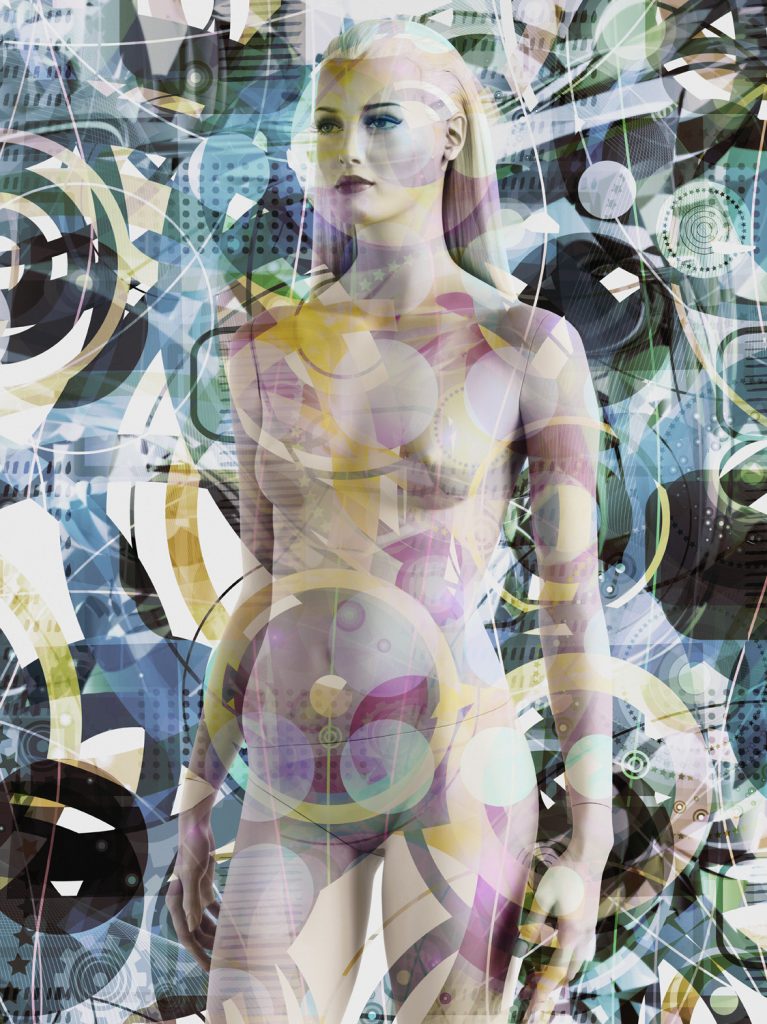

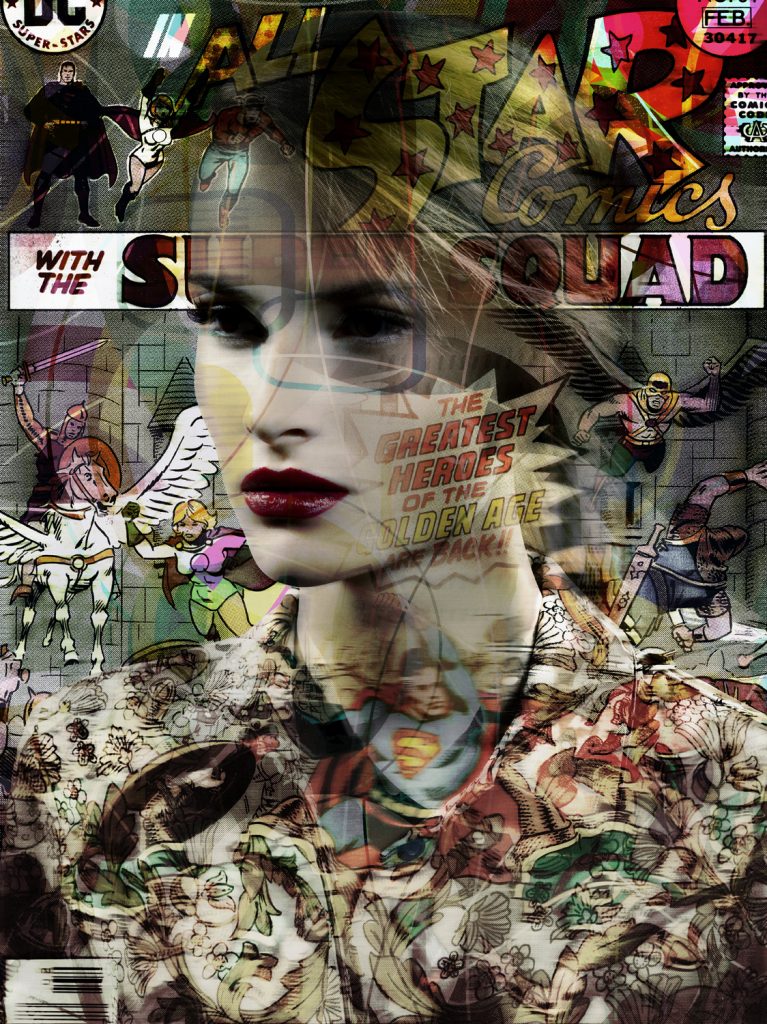

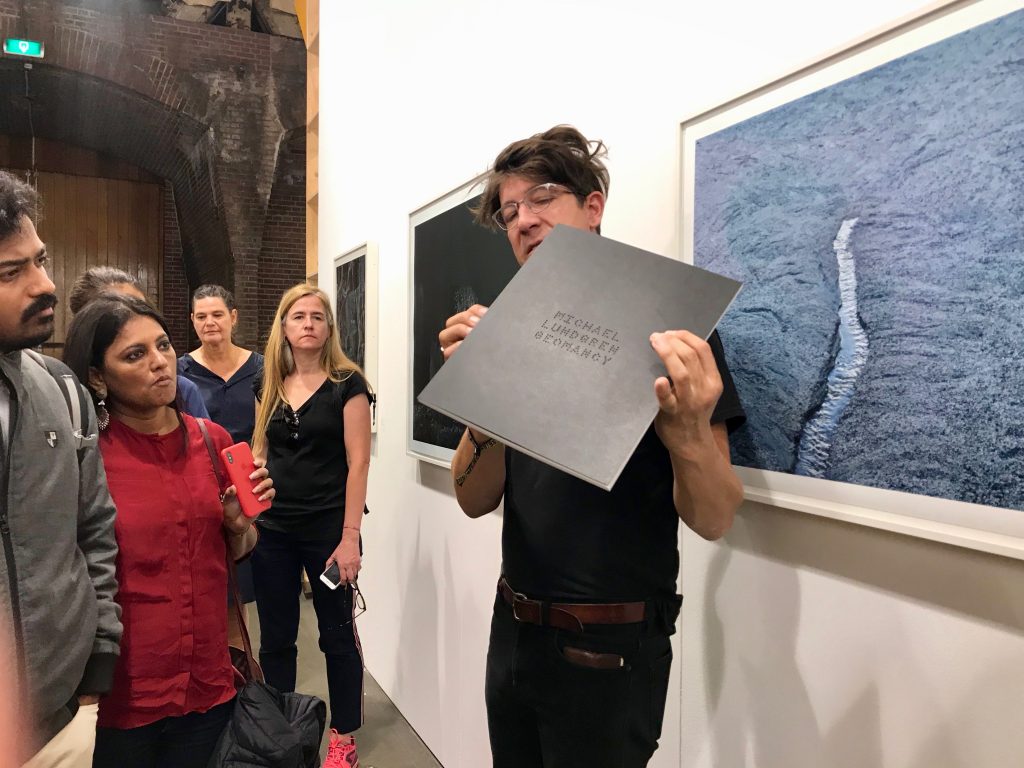

In all cases, the most appropriate focus for the exhibition would be my own image making, though it would be possible to find a way to show how the collaborative process has fed into this. To give this aspect of the work it’s own life and identity has the advantage of taking the strain off other aspects of the work (for instance, the community portraiture), allowing this work to develop at it’s own pace without threatening the completion of the FMP. To an extent, this reflects the point made by Laura Pannack in the presentation this week, regarding the benefits of a self-contained project with distinct deadlines. Operationally, this doesn’t really depart from the plan mapped out in the FMP proposal, but psychologically it brings a degree of clarity about the FMP which will be particularly useful in making a pitch to the galleries. The production of opportunistic pop-up exhibitions relating to the various micro-projects will continue as planned, and these will influence the images made for the FMP. The pdf submitted, and the Critical Review of Practice, can show the nature of this influence, but the FMP pdf will be built around the images presented in the exhibition. The next step is to secure an exhibition space and time. I’ll make a presentation at the Open Project Night at The Warehouse on 20th November and take it from there.