According to the schedule, at this point (Week 14) I should have completed my fieldwork, and be working on composites and other images for the outcomes of the project. Seems like a good time to review progress to date and map out activities for the next 4 months.

Photographic Fieldwork

Image making for and with community groups has been pretty intense over the past few months.

Thames Ward Community Project (TWCP). Following on from a series of photographs of the members of the Citizens Action Group, I decided to focus on activities within the community. Consequently, I have made images of the following activities: TESOL for Parents (two sites – Riverside and Thames View), Mums with a Mission (Thames View), DJ workshops (at Riverside Campus: see selected images below), Thames Ward Health Stakeholders, Young Citizens Action Group.

A repository of photographs has been created and I have made prints for the project leaders and participants. Prints from projects have been used to raise awareness of the different activities amongst the project team (for instance, at the recent project dinner).

Photographs have been used in press and promotional material. The 100 images made for the Thrive Community Day have been given to the Mental Health Foundation for the report on the Thrive Thames View project. Next step is to produce a collection of larger prints for the TWCP to use in promoting its work.

New View Arts. My Shed Life photographs (of participants, the area and the models produced) have featured in the press and funding campaigns. They have also been used in the report produced by University of East London architecture students and in support for the planning permission application. I would like to submit images to the WISERD Civil Society Photography Competition, which closes on 13th January. I will continue to make images with the group to feed in to the exhibition planned for the opening of the Shed and any prior promotional work. The Arts Council funded film on the Creekmouth flood and displacement, to which the summer workshop for children contributed, was presented to residents on 2nd November and I gave to prints of photographs used, including archive photographs, to the group. The film was also shown to the public at the Sue Bramley Centre, with accompanying pop-up exhibition of my images and photographs taken with and by the workshop participants, on 13th December. Future showings are planned.

Everyone, Everyday. This is the local incarnation (and most prominent project) of Participatory City. I have joined the project and attended events, and discussed the possibility of exhibiting at the Warehouse with the facility manager and running workshops with the project officers. Their next planning cycle starts in January, and I have a meeting with the Barking project team on 9th January to explore contributing to the programme of activities, which starts on 25th February.

Eastside Community Heritage. Photographs of the demonstrations relating to the Riverside Estate fire, and images of the estate, are being used in the independent report and the website being produced around resident accounts. They have been used in press coverage, and a BBC feature was made with footage from the demonstration on 19th October. Follow up with residents planned. Possible collaboration with ECH producing images for their Becontree Estate project. ECH has previously collaborated with Studio 3 Arts on the Open Estate project, focusing on the Gascoigne Estate.

Barking and Dagenham Heritage Conservation Group. I have continued to to attend meeting and kept in touch with activities. I have made images of developments around Barking, and collected a list of proposed developments from emails about applications for planning permission. May be possible to draw work together for a pop-up exhibition in the town centre (for instance, at the Barking Hotel). Another possibility would be to do a collaborative piece with Keith, who has a particular interest in photography, particularly with film, or to focus on some of the members of the group and their concerns. Might fall outside the scope of the FMP.

Greatfields School. On 8th October, I ran a workshop for GCSE Photography students to introduce a collaborative project focusing on the impact of changes taking place on the Gascoigne Estate. Kiran (the photography teacher) repeated this with another group, and invited proposals for projects from the students. These have been submitted and projects selected. We plan to run the sessions after school on Thursdays, alongside the photography club. Pressure of work around the end of the year have led us to postpone the project start to 23rd January (to run for 6 to 8 weeks).

Exhibition and engagement

Work has been exhibited locally in pop-up (such as the Creekmouth film showing) and other exhibitions (such as the IG11 Art Trail, which ran until 9th November) as planned, and used in community engagement and dissemination activities (for instance, the Community Day, TESOL for parents and DJ workshops). These opportunistic exhibitions will continue. For the FMP outcome, however, something more formal will be needed, which can incorporate and showcase my own work. I am pursuing a number of possibilities, and the London Creative Network will give rise to new opportunities, including the new block at Barking and Dagenham College and the Warehouse. Most likely is the Sue Bramley Centre, which has good outside space in which work could be displayed without danger of vandalism (which would be a problem with the hoardings in the areas, which would otherwise provide a good display surface).

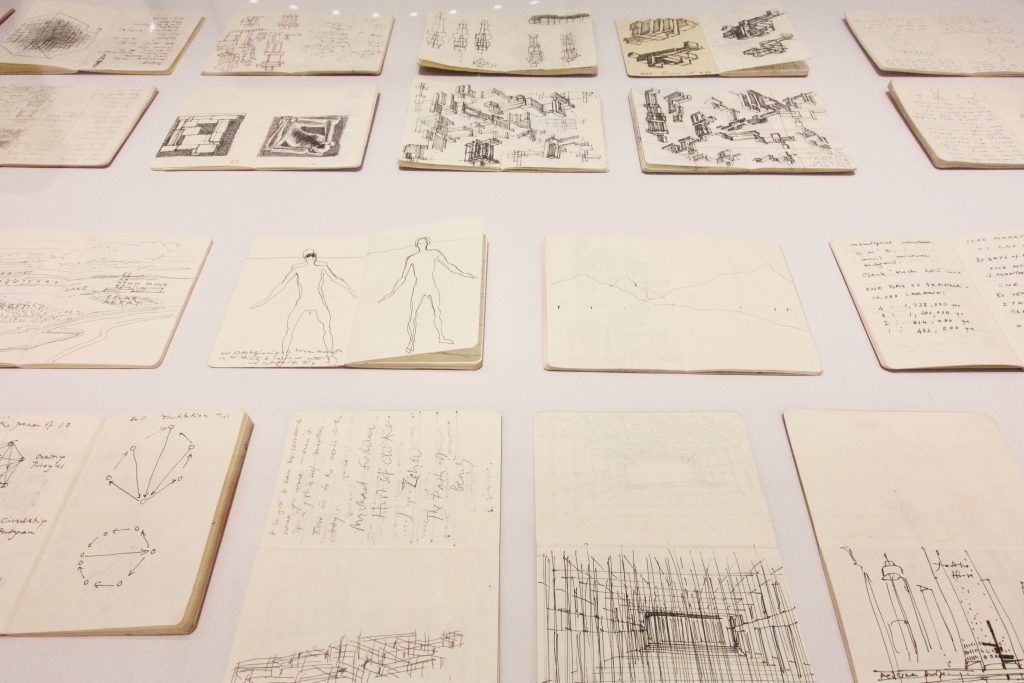

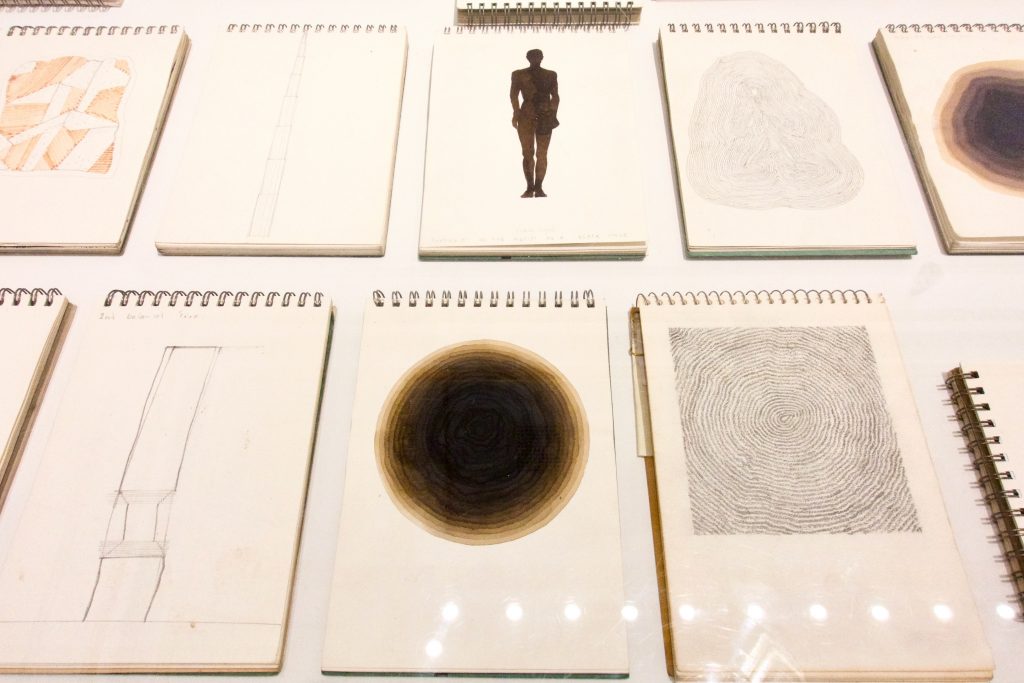

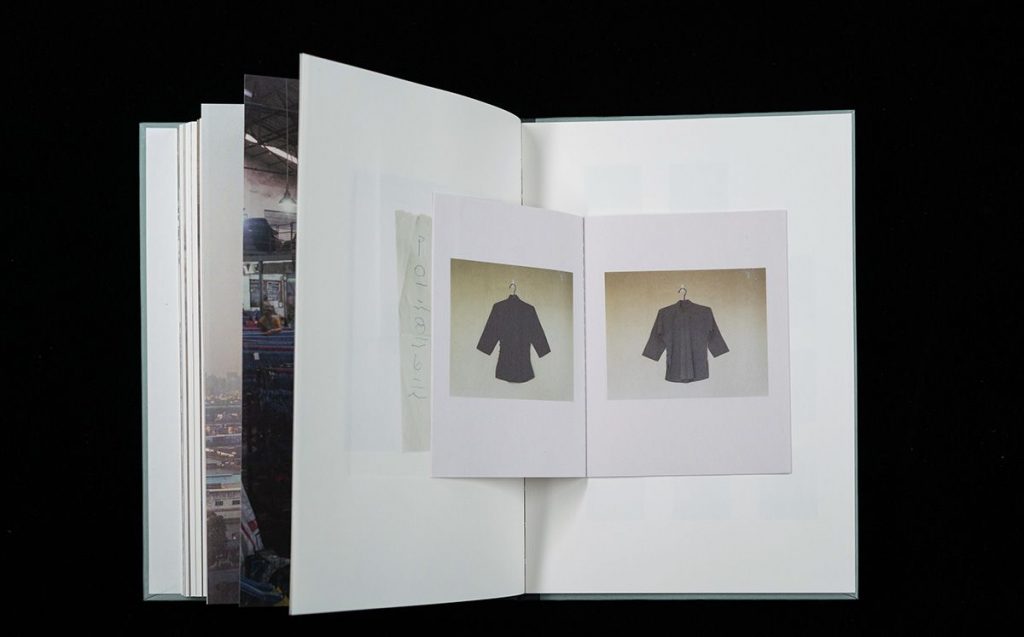

I have discussed this with the centre manager, who is supportive of the idea. Other site specific exhibitions could also be organised. I have also discussed the possibility of running workshops at the Centre, for TWCP project leaders and at the Warehouse. At this point, there are ample viable sites for exhibition and engagement, but this will have to be tied down in the coming month, and work produced for exhibition if this is to be a principle outcome of the FMP. I am also exploring handmade books as a way of displaying photographic work in easily portable form (I’ll make a specific post about this).

Next Steps

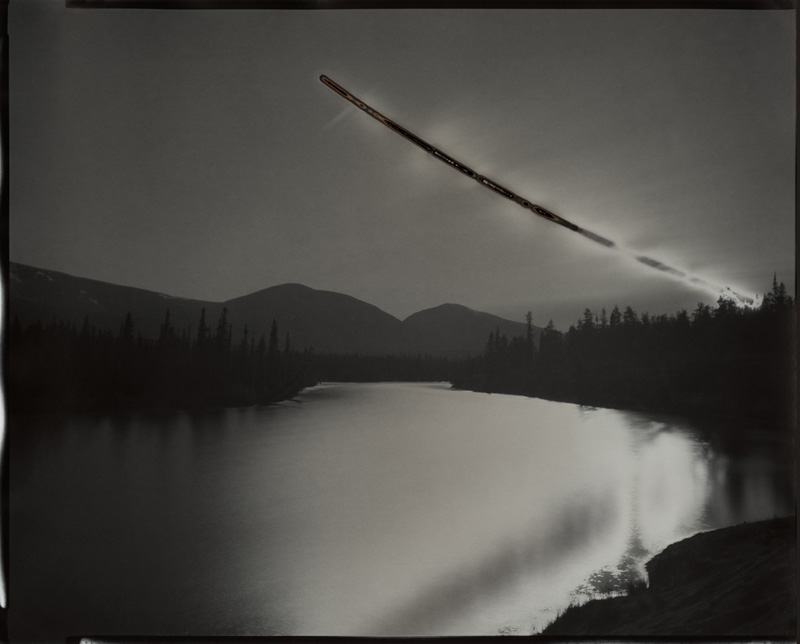

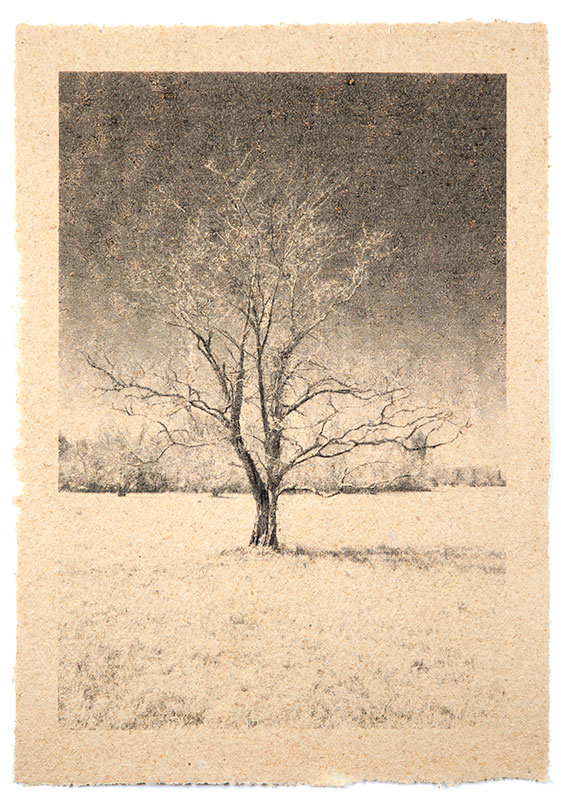

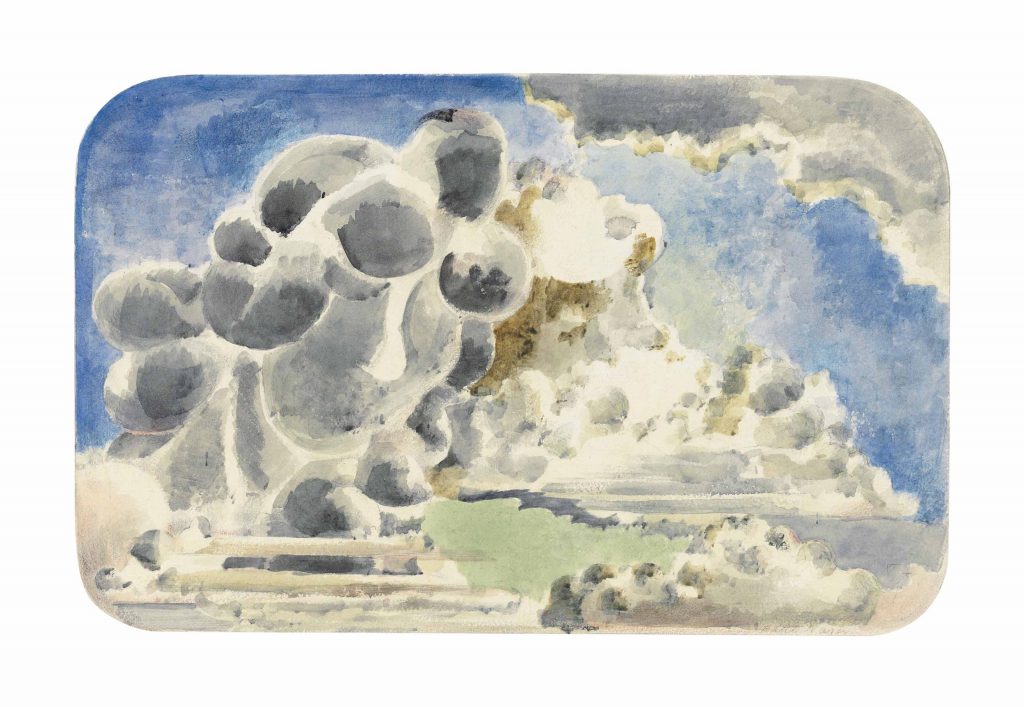

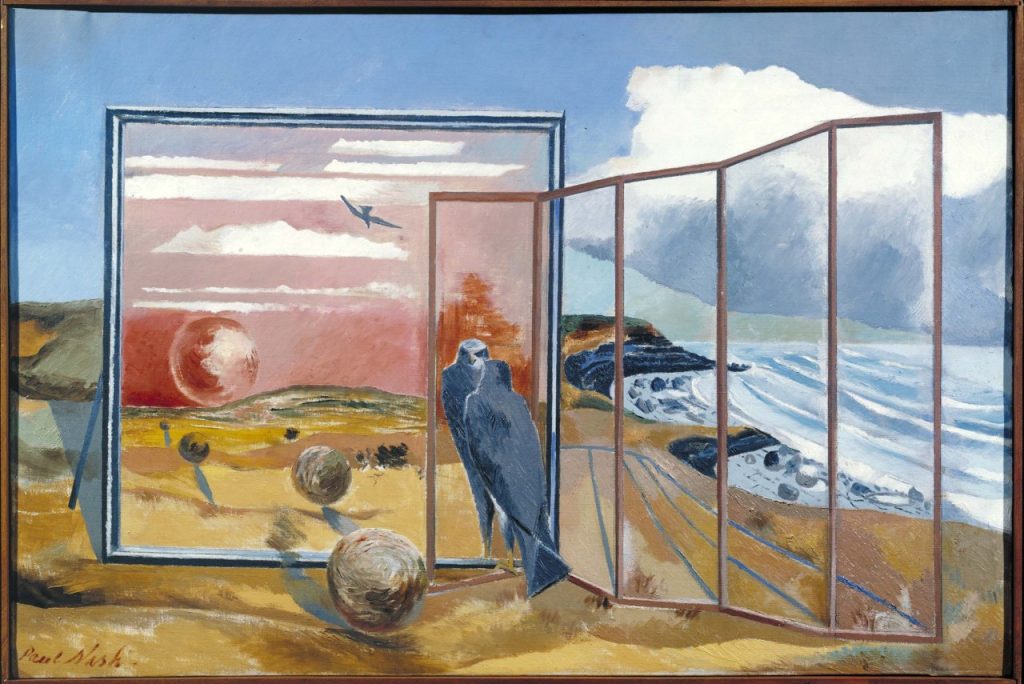

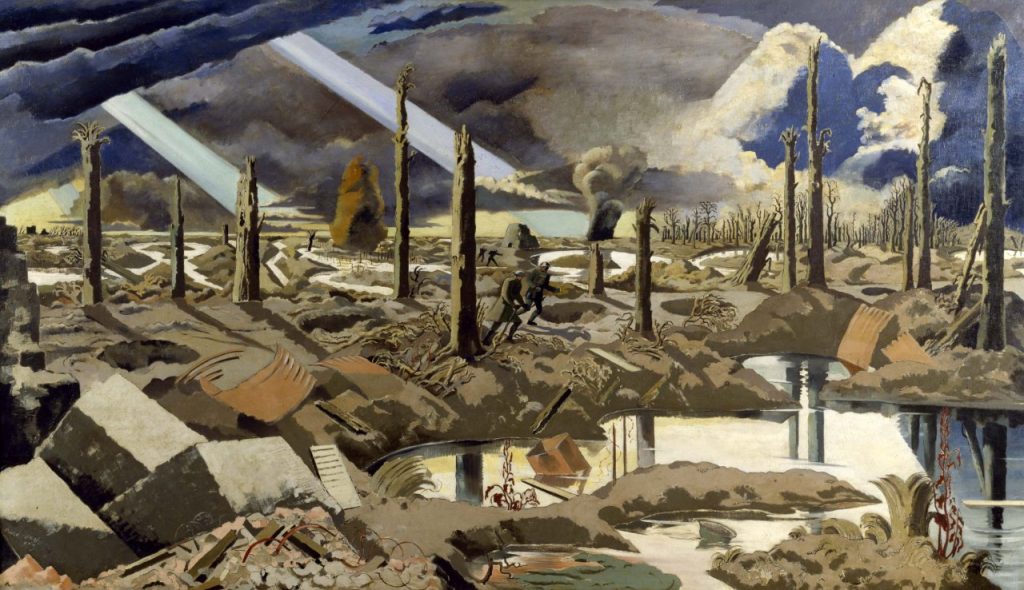

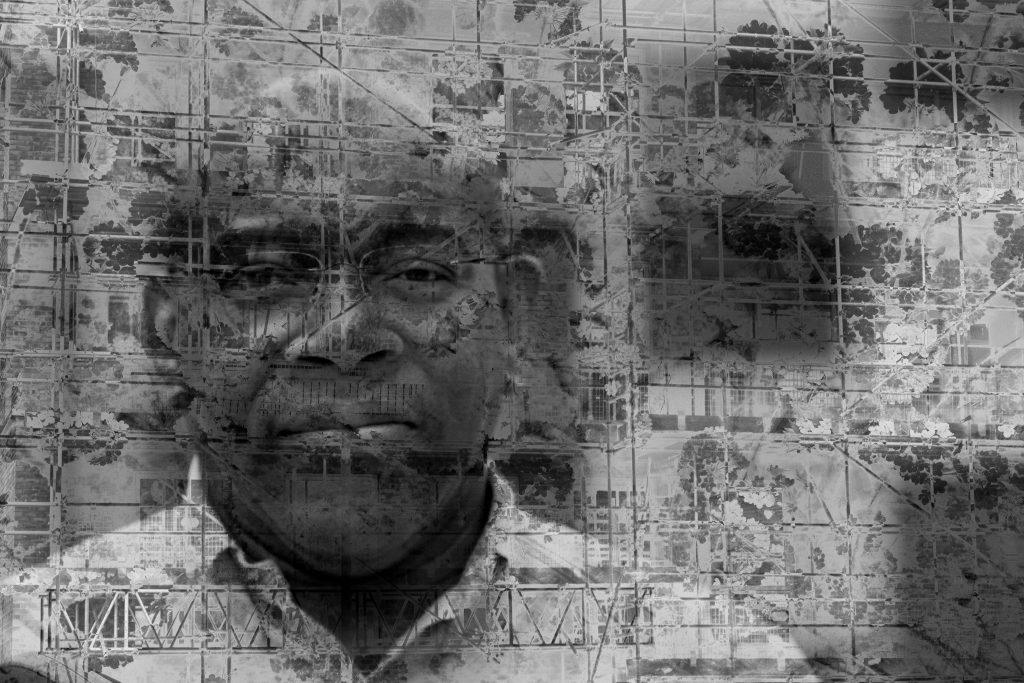

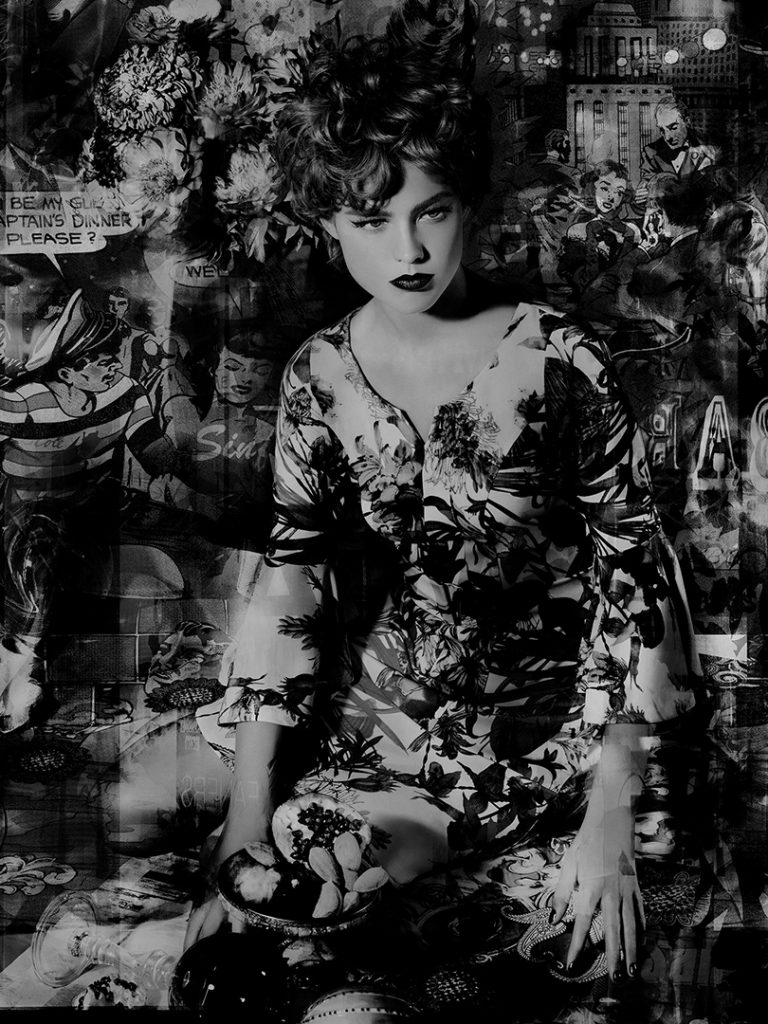

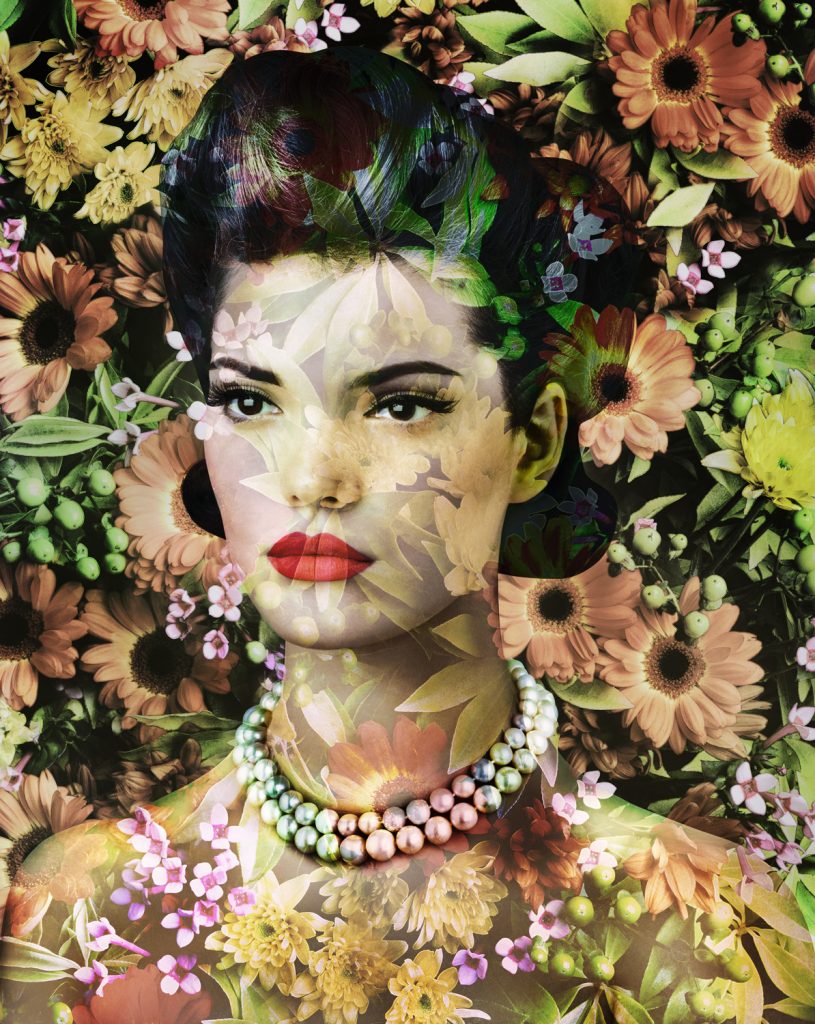

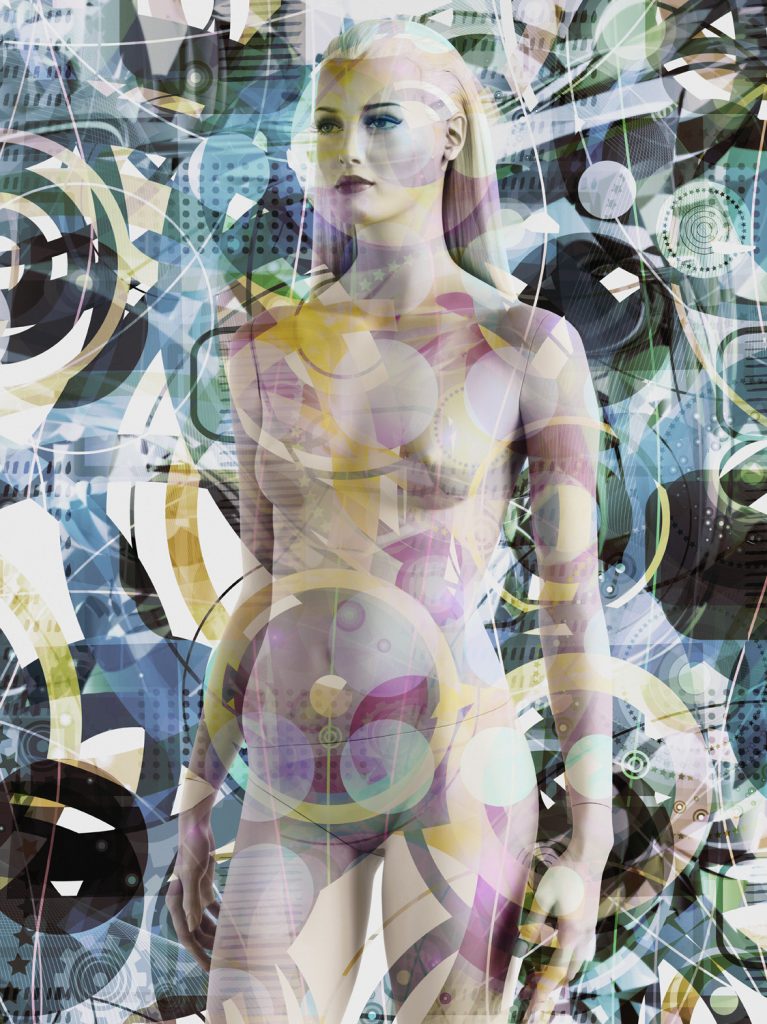

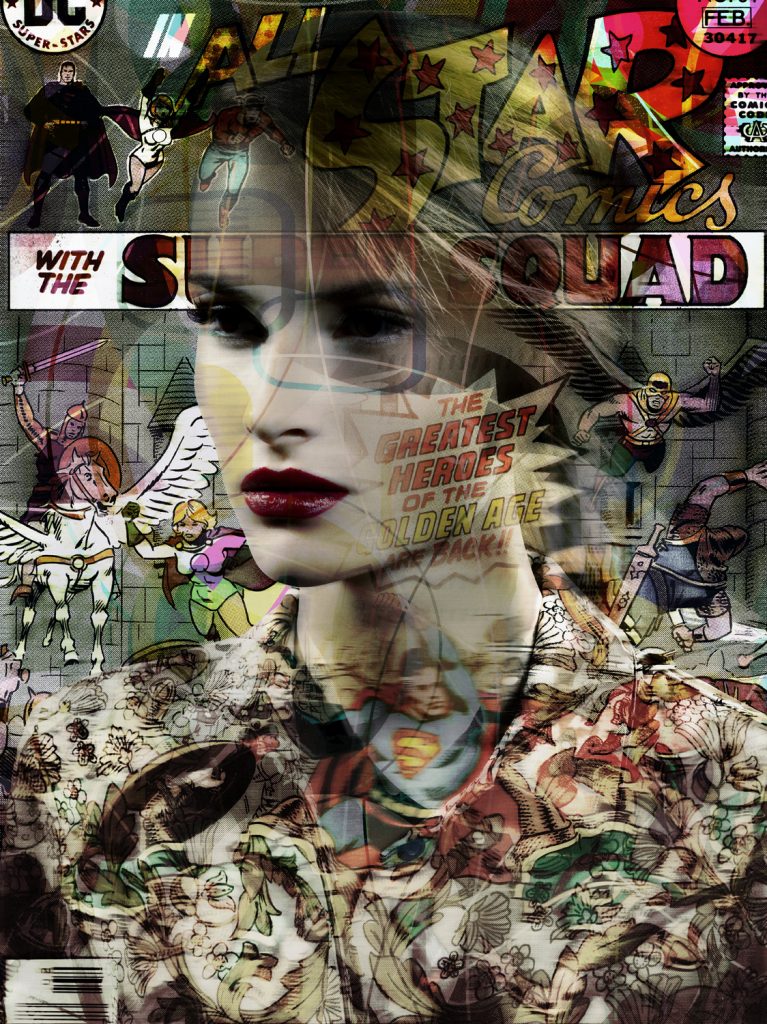

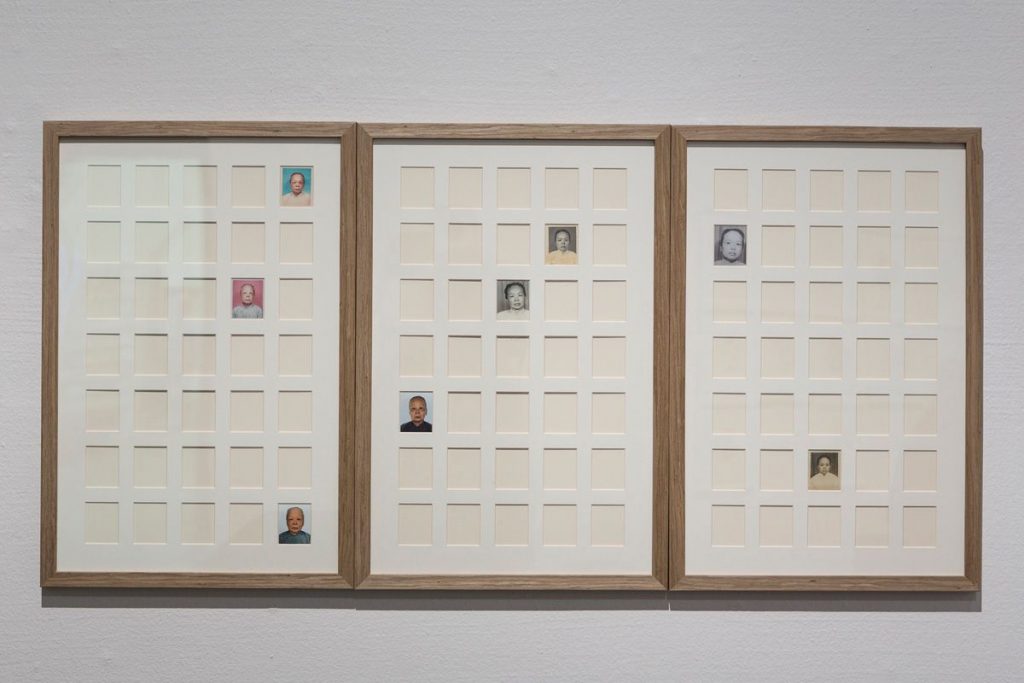

I am currently collating images and other material (including maps, planning documents, data and archive images), and exploring how these can be juxtaposed. Ethically and practically, I am inclined now to identify a number of key collaborators, and a narrow range of themes, and to work with them as models, and in selecting images with which to work. Over the next two weeks, I need to produce a range of images to exemplify the form of outcome, and/or to act as base composite images to which to add images of members of the community. Alongside this I will identify the most appropriate ways of disseminating and exhibiting the work. I will also produce a range of forms of book to illustrate how the work might be transported and shown. In addition to the photographic work for and with community groups, I have been exploring the boundary between the Riverside development and Footpath 47, which runs alongside the Thames. Currently this gives direct access to the riverbank, but under plans for the estate development, will become a paved walkway between the housing and the river, which will dramatically change the local ecosystem, and access to the marshland environment. In addition to the community related composite work, I will explore the environmental aspects of the development through the incorporation of environmental effects on the images themselves (see, for instance, the discussion of work by Matthew Brandt; I have collected samples of water from the marshes and rivers to experiment with the effects on images). Related to this, I want to visually explore the boundaries that are being created, and the conceptual limitations of the notion of boundary in understanding the entanglement of human activity/well-being, the built environment and the natural environment. From this work I also need to produce a clear statement of the focus of the FMP (as a subset, or intermediate stage, of the wider project) – a post will follow about this. Commencement of the LCN programme at the end of January will also have an impact on the development and ultimate focus of the FMP outcomes.

Revised schedule

Whilst progress with the work has been good, and largely to schedule, there is a need to fix the focus of the FMP and revise the schedule to ensure that adequate time can be give to the work that needs to be done. The revised schedule looks something like this:

Composite image-making and preparation of prints prototype books (16th December 2019 to 12th January 2020)

Week 13 Collation of images and documents

Week 14 Creation of initial composites and other images

Week 15 Printing and preparation of images and prototypes

Week 16 Final determination of project focus, collaborators and outputs. WISERD images submission.

Sharing of composites, creation of images, feedback and preparation of cumulative outcomes (13th January 2020 to 23rd February 2020)

Week 17 Image making with participants. Commence work with Particatory City.

Week 18 Image making with participants. Commence Greatfields project. Commence LCN programme

Week 19 Image making with participants

Week 20 Image making with participants. Thames Ward Growth Summit exhibition

Week 21 Production and presentation of work

Week 22 Reflection and follow-up with participants

Final outcomes: exhibition, artists book/archive and workshops (24th February 2020 to 5th April 2020)

Week 23 Preparation of material for exhibition and workshops

Week 24 Warehouse exhibition and workshop. Complete Greatfields project

Week 25 Falmouth workshops and portfolio review

Week 26 [Singapore & Canterbury]

Week 27 Workshops and exhibition

Week 28 Finalisation of outcomes.

Preparation of FMP submission (6th April 2020 to 1st May 2020)

Week 29 Review CRJ and online portfolio (Easter)

Week 30 Finalise Critical Review of Practice (Easter)

Week 31 Finalise Project pdf

Week 32 Submit Project pdf and Critical Review of Practice