The Tyranny of Story, Parts 1-3, BBC Radio 4, August 2018.

I listened to this three part documentary presented by John Harris on BBC Radio 4 as preparation for a workshop run by co-producers Nina Garthwaite and Alan Hall. The workshop was cancelled, but the programmes raised a number of issues of relevance to the development of my project. In an earlier post, I raised questions about the extent to which photographers can be considered to be storytellers. Following up the programmes, I think I now have a clearer position on this, which can help inform my work. A distinction is drawn between whether (i) our lives fundamentally have a narrative structure, or whether, (ii) whilst episodic in form, our lives should, for our own well-being, be rendered as a narrative, or whether (iii) for mutual comprehensibility and engagement our lives can be presented in narrative form, or whether (iv) presenting lives as narratives is, at best, a distraction or, at worst, a damaging mis-representation, that creates unattainable expectations and encourages self-deception. Galen Strawson’s work, which sees life as episodic, and narrative as a misleading construction (see, as a brief introduction, Strawson, 2015), is interesting in respect of the last of these positions.

It is clear that there is a popular demand for stories/narratives, and that, in order to convey a message, narrative form is a powerful resource. Personally, I like telling and listening to stories. They provide a powerful means of communication, interaction and dialogue. Taken into the political and commercial domain, of course, this desire for and attraction to compelling stories can be used to distract and mislead. Reflecting on the decline in MMR vaccination, for instance, the case is made by neuroscientist Tali Sharot (a colleague from UCL) that stories (whatever their foundation) of catastrophic damage to a loved one hold greater emotional appeal than the narrative of the collective (and individual) benefit of eradicating forms of childhood illness founded on scientific research. The puzzle here is understanding the motivation for construction, propagation and subsequent narrative dissemination of these ‘alternative facts’. One argument might be that this is a popular reaction to professional discourse which dis-empowers ‘ordinary people’.

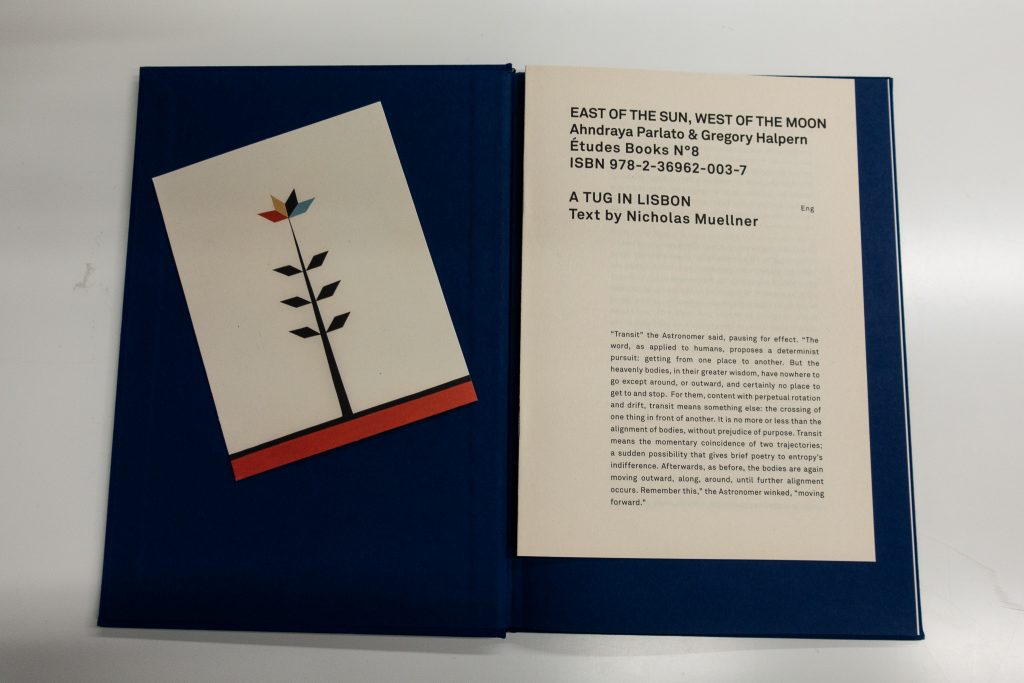

Whilst some photographers might feel that they are revealing narratives, others may see themselves as constructing narratives. I sit more on the construction side of this, but showing respect to, and in dialogue, and possibly collaboration, with the people being photographed. In this, I lean towards a desire to disrupt narrative form to allow different accounts to be explored and to enable new dialogues. Narrative can be powerful in drawing and holding attention, but is not an end in itself, and ultimately if the production of a greater understanding of others, more open dialogues, new forms of knowledge and new ways of knowing are the desired outcome, subversion of established, and expected, narratives is inevitable.

I’ve talked myself out of being a storyteller here, recognising that story can be a valuable resource, hook or medium, but understanding that this has to be undermined in order to create the space for new dialogues. Maybe I’m a teller of provisional and unstable stories (or a provisional and unstable storyteller). In order not to continuously tell each other stories we already know (and that reinforce our prejudices), and to make space for other ways of being and knowing, we need a wider range of resources, strategies and tactics. A way, maybe, of inquisitively making and unmaking, synthesising and deconstructing narratives to produce something new.

By chance, a few days later I stumbled into another Nina Garthwaite project, the Soundhouse at the Barbican. Here, she and collaborators are attempting to bring creative podcasts into public space, in a gallery-like listening environment. I’ll explore that elsewhere, as part of consideration of ways of presenting work, and the potential of the gallery as a space for public reflection and engagement.

References

Strawson, G. (2015), ‘I am not a story’. Accessed on 29.09.18 at https://aeon.co/essays/let-s-ditch-the-dangerous-idea-that-life-is-a-story

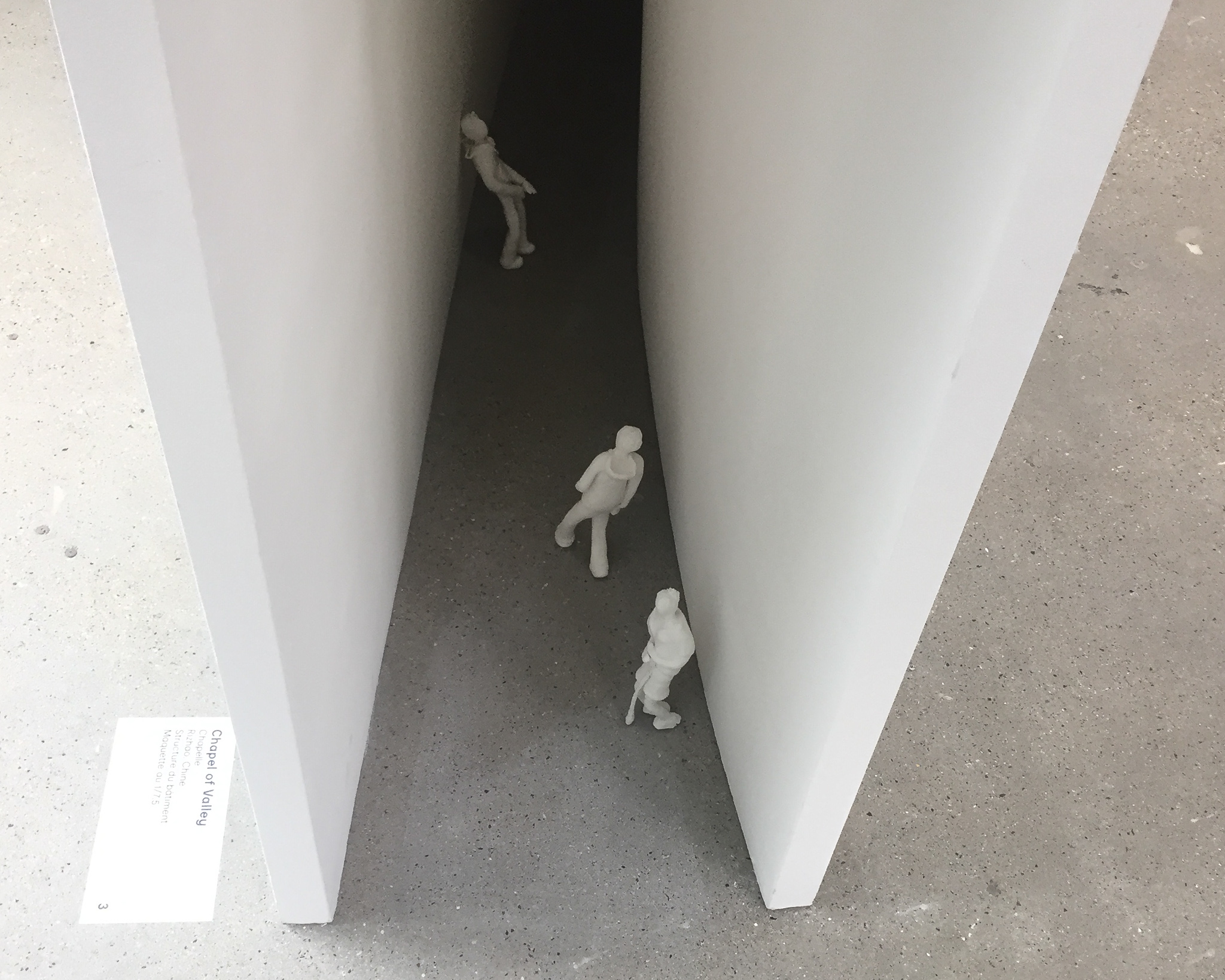

An extensive survey, covering both floors of the gallery, of the work of a radical Japanese architect. In a discussion in the previous module, it was stated that how a building will look when photographed was influencing architects in their designs. The absence of photographs in this exhibition is notable.

An extensive survey, covering both floors of the gallery, of the work of a radical Japanese architect. In a discussion in the previous module, it was stated that how a building will look when photographed was influencing architects in their designs. The absence of photographs in this exhibition is notable.