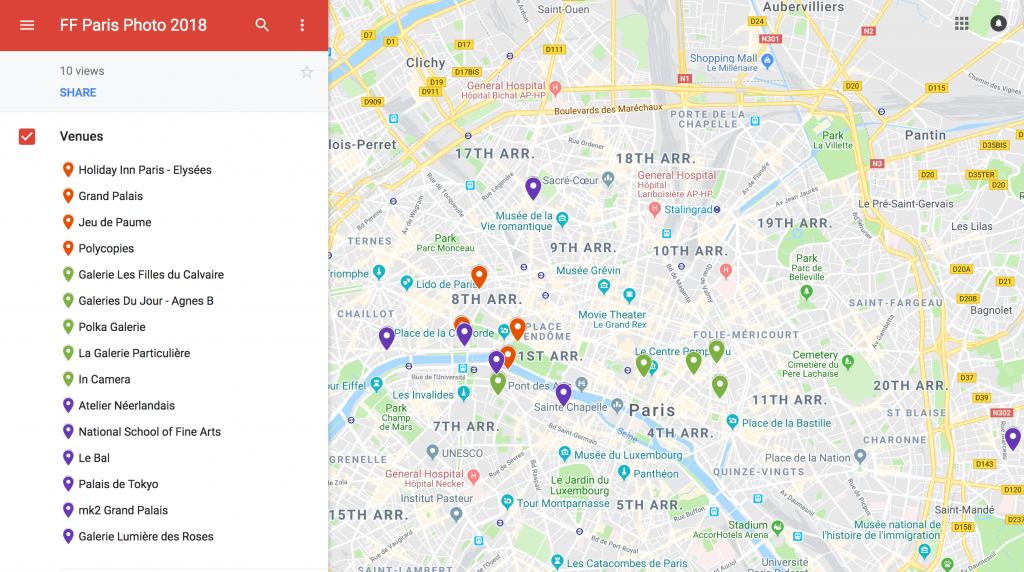

Artist Self-Publishers’ Fair, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 8th and 9th December 2018

A really great way to finish the module for me. Having explored social media and other ways of promoting and disseminating work online, and building a profile, it was good to explore critical alternatives at the these ICA events. The Saturday session comprised of presentations and a group discussion. Highlights for me were the overview of the history of and relationship between political and artistic self-publishing provided by Nick Thoburn, the insight into a small scale community arts initiative (based in my own area of east London) by Sofia Niazi from OOMK and Erik van der Weije’s account of his transition from independent publisher in Brazil to lecturer in Holland (which involved giving away all his remaining publications – I got a copy of his Oscar Niemayer book).

Thoburn presents the strength of self-publishing as residing in its ability to create its own context (to be self-institutionalising) and the small scale, intimacy, tentativeness, vulnerability and emergent nature of its outputs. It is, for him, a fundamentally political activity, and lies in opposition to the the commodification of art and the institutionalisation of knowledge. Need to follow-up on Infopool and Mute Magazine, both of which address issues around the arts, regeneration and London. And his 2016 publication Anti-Book: On the Art and Politics of Radical Publishing.

One Of My Kind (OOMK) is a collective publishing practice based in Manor Park. They run a community printing press and courses for local people (Rabbits Road Press). Good local contacts to have for my projects, and their project The Library Was is very relevant to the social infrastructure dimension of my project. Was able to talk to them at the Fair on Sunday and will visit in the New Year.

Also spoke to photographer Erik van der Weijde about his transition from zine production and publishing to teaching at the Rietfeld Academy, and my own journey (more or less) in the other direction. A good introduction to the challenge (and economics) of small-scale self-publishing. His 2017 publication This is not my Book explores photography and independent publication.

Over 70 exhibitors at the fair on Sunday, and lots of examples of forms of publication to consider for my own work, and work that I’ll be doing with community groups. Particularly liked the work by OOMK and by Roberts Print. A lot of potential for a hybrid (online/print) publication strategy for my own work. The event helped to see the positive (critical and oppositional) dimension of self and small-scale publication, and provided contacts in this particular community to follow-up. And helpful to make tangible links between the themes of this module and the next two modules. Much of the work in this area is strongly theoretically informed, which links with Informing Contexts, and the outputs as books, zines, small print runs, events and workshops relate closely to the themes to be explored in Surfaces and Strategies.

The purpose of this post is to put down a marker around these themes and to form a bridge between Sustainable Prospects and subsequent modules, in relation to the development of my own practice and progress towards my final major project. I’ll return to all the themes signaled here in later posts.

OOMK (2016). The Library Was. Berlin: Fehras Publishing Practice.

Thoburn, N (2016). Anti-Book: On the Art and Politics of Radical Publishing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

van der Weijde, E. (2017). This is not my Book. Leipzig: Spector Books.