My own objectives for this module were: (i) to explore new forms of image-making; (ii) extend my engagement with and knowledge of contemporary theory in photography and visual arts; (iii) develop a stronger conceptual basis for my practice; (iv) position my photographic practice within inter-disciplinary enquiry and multi-professional practice; (v) progress with my project, including the development of skills and networks. I think I have made good progress in all these areas. In this reflection I will relate progress with these to the learning objectives for the programme.

The reflection will be prospective (looking forward to the completion of the degree) as well as retrospective (looking back over Informing Contexts).

LO1: Technical and Visual Skills.

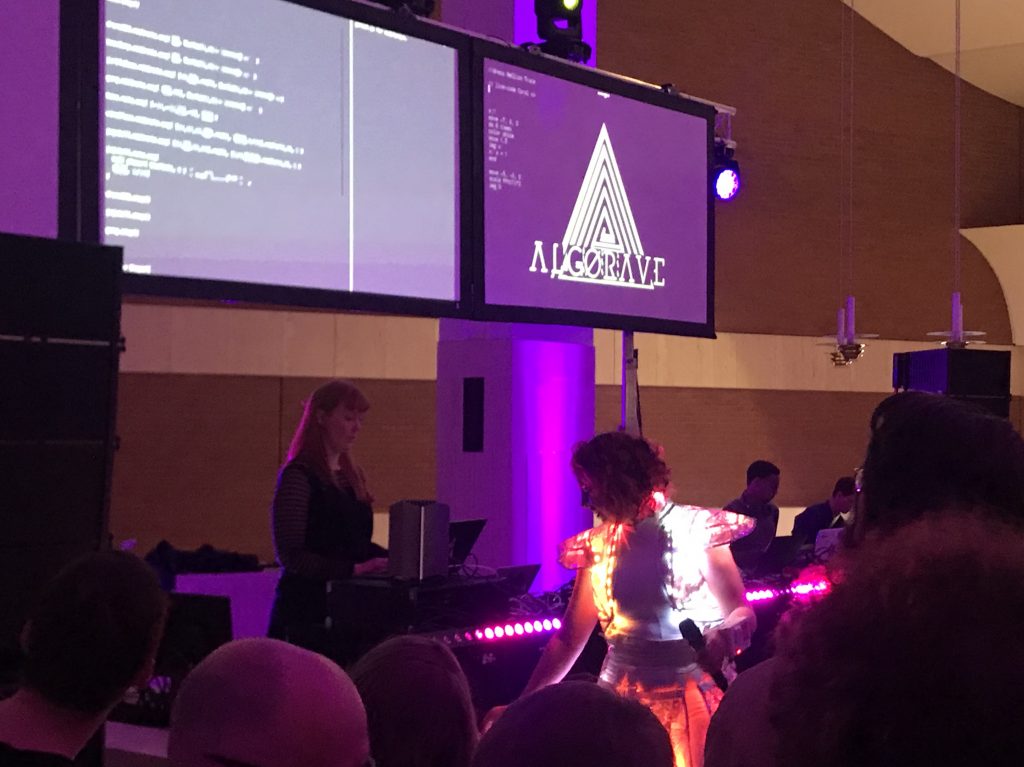

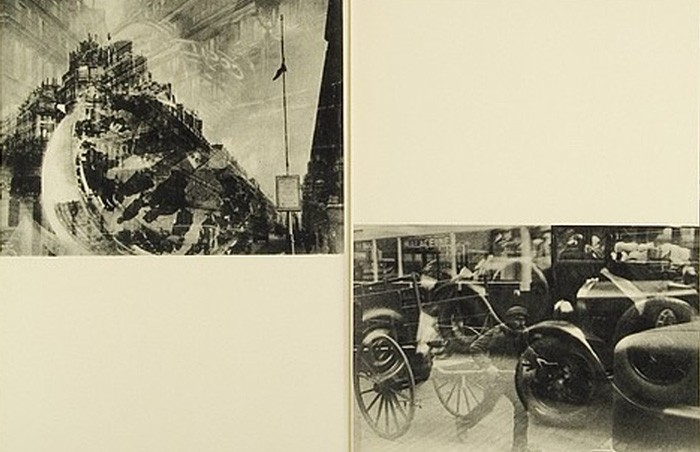

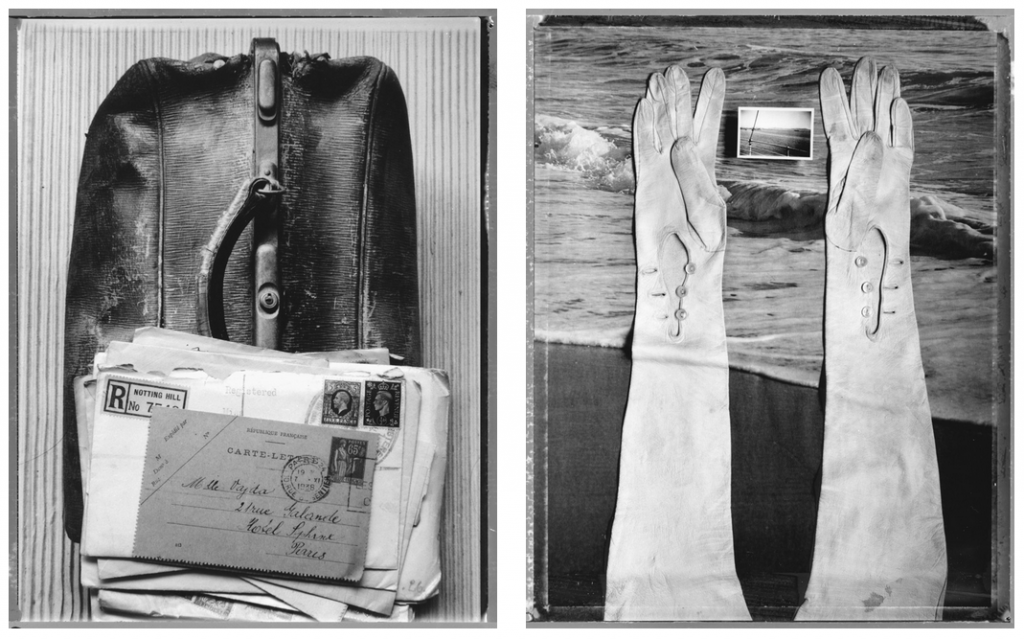

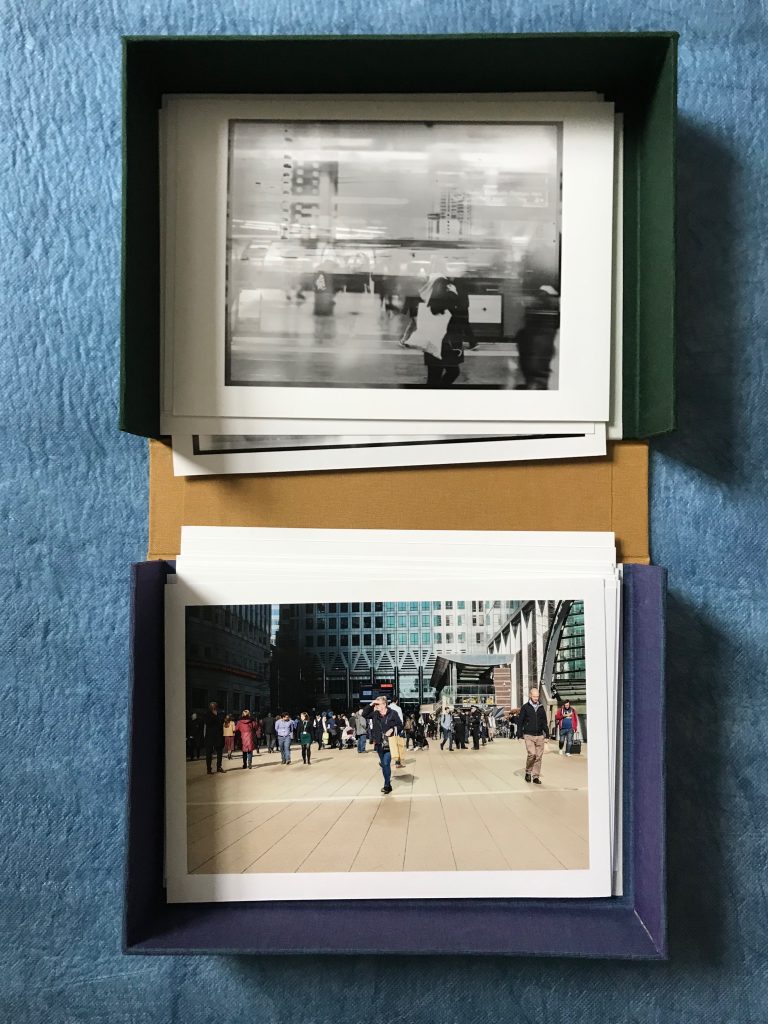

I came to the module technically and visually competent in particular forms of image making, working both in film and digital media. I wanted to both improve and extend the scope of my work, and experiment with new approach to image-making. The workshops and the portfolio reviews in Falmouth helped me with this. The principal areas of development over the course of the module have been in the shift to making constructed images (inspired by the early Informing Contexts lectures), the production of composites and the creation of animations – all new areas for me. See portfolio and CRJ entries. Alongside this I have continued to develop portraiture and still life work in community and museum contexts, and environmental and urban landscape work in the photographic study of urban regeneration. The work in my portfolio, though in the early stages of development, and the other images included in my CRJ, demonstrate that I have an in-depth understanding of a range of photographic processes, and I hope displays sophistication in the application of techniques.

LO2: Visual Communication and Decision-Making.

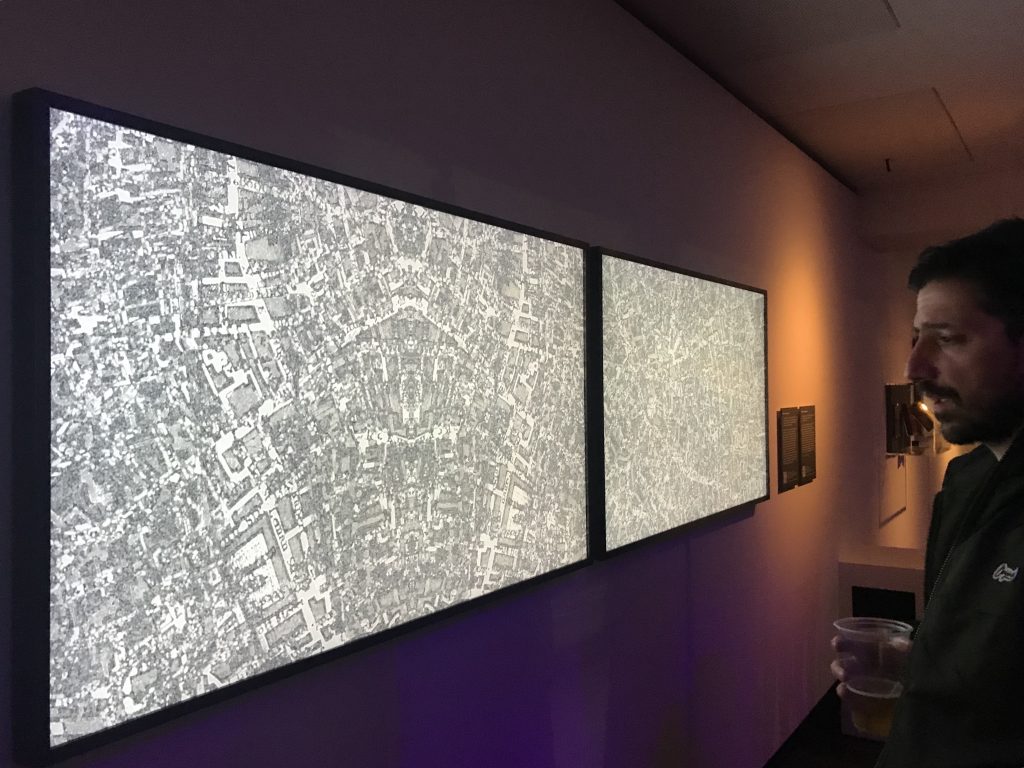

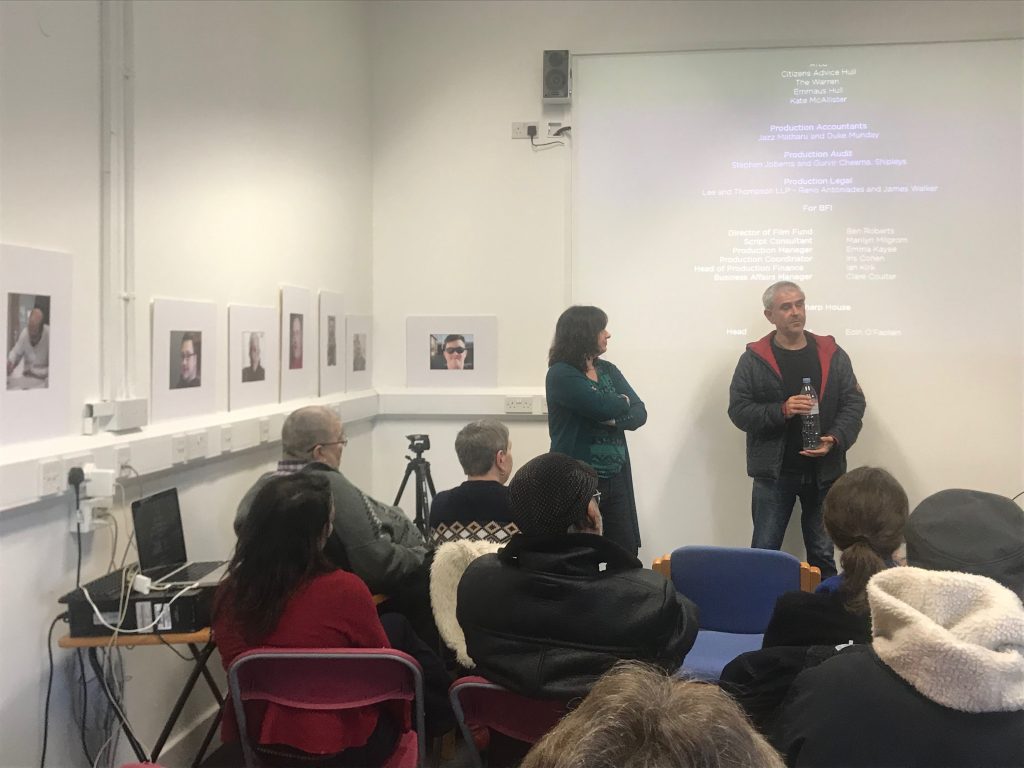

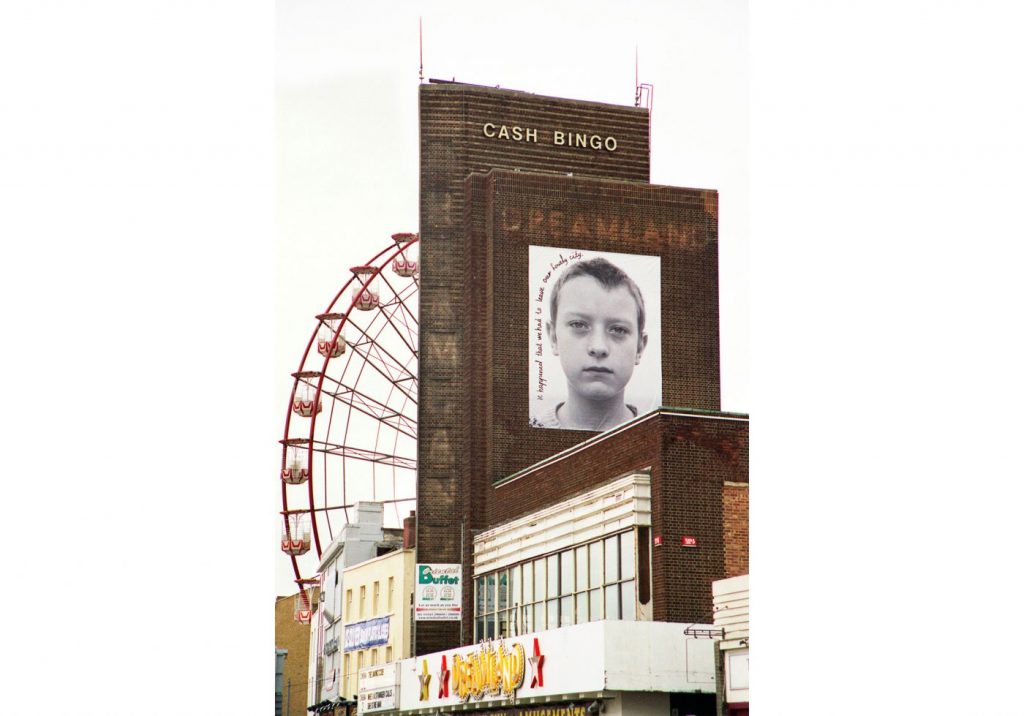

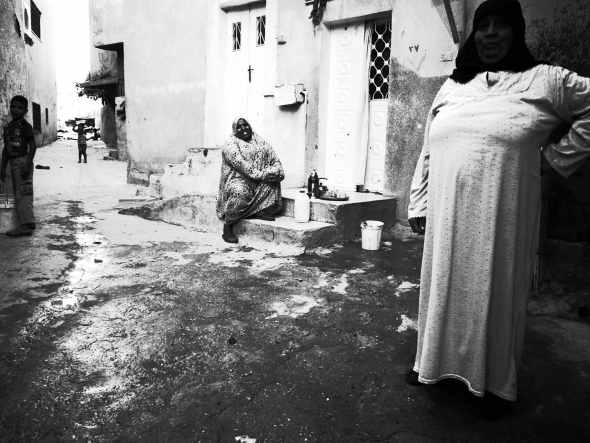

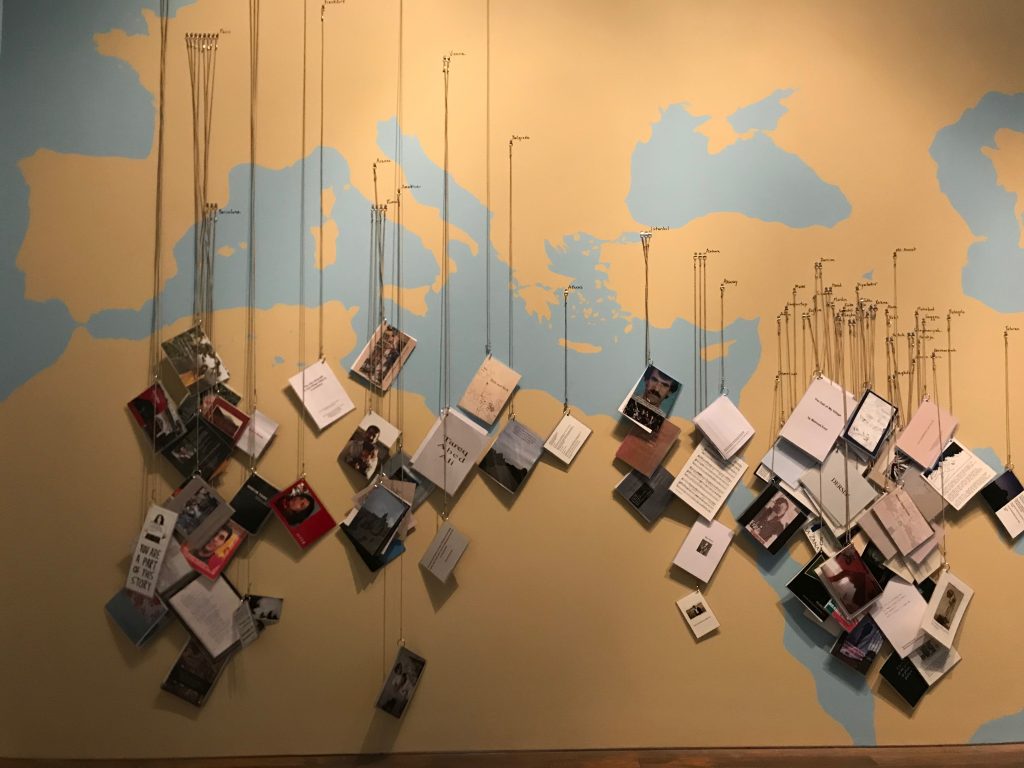

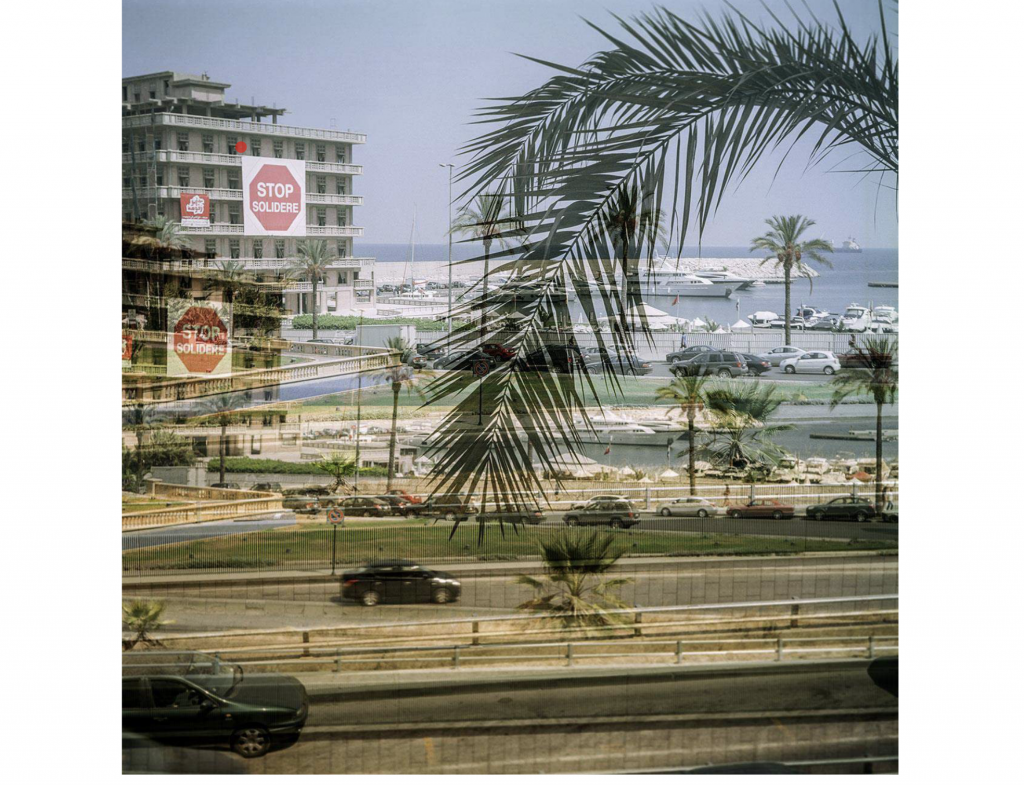

Focusing on the relationship between human activity, urban development and the natural environment, and exploration of conceptions of time in relation to this relationship, has helped me to develop a clear conceptual basis for the work and a clear visual strategy and method. This has informed decisions made in the production, editing and presentation of images (for instance, the inclusion of animations and the form taken by the online portfolio in as a mode of presentation of the work). There is still a lot to do to develop this work further. It is, though, just one part of the work I have been doing towards my project. I have also exhibited work in print form (for instance, the exhibition of portraits of community project participants at a local community centre, and the creation of image banks with community activist groups. I have also worked with museums and galleries and with undergraduate students on the use of photography in object based learning, and the creation and exploration of archives. Although my portfolio is presented online (which I feel is appropriate for an online course), my principal interest, in the presentation of work, is in the production of prints, books and artefacts and their presentation in multi-modal exhibition and installation form. I hope that the work in my portfolio demonstrates a level of sophistication in the production and presentation of my visual work and the ability to communicate complex ideas.

LO3: Critical Contextualization of Practice.

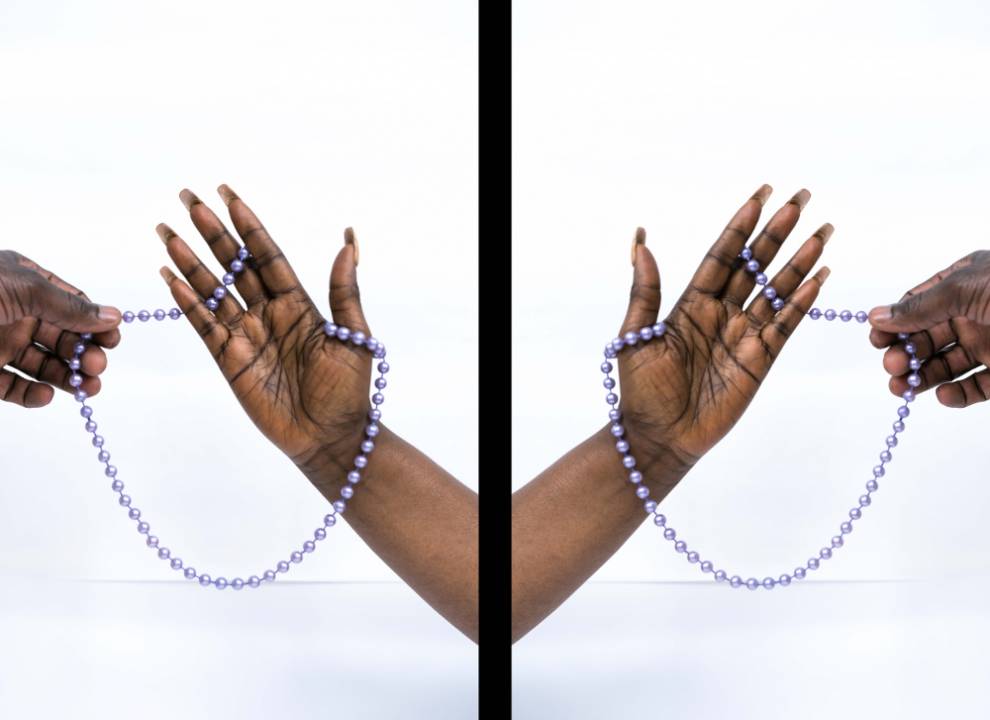

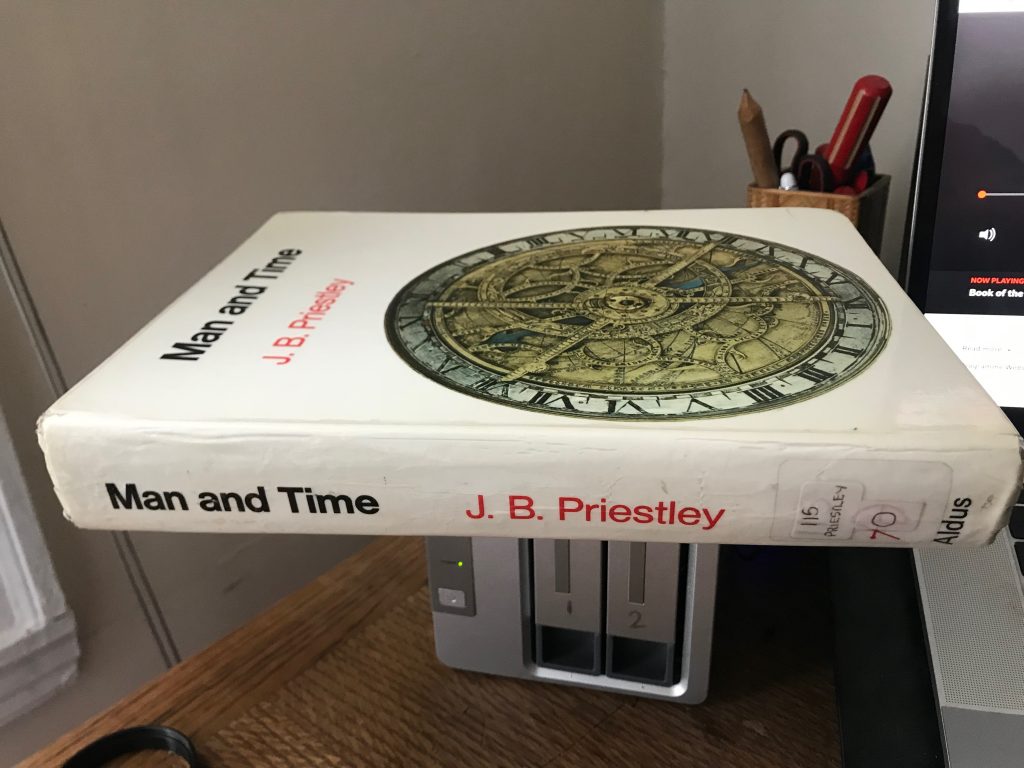

Ethical concerns about covert forms of photographic work led me into more collaborative forms of image making. I have continued to develop this with my community focused work and work with students and museums. Moving into more constructed and manipulated forms of image-making in this module has led me to explore a greater diversity of forms of work in photography and the visual arts. From my CRJ it will be clear that I have become particularly interested in the work of Japanese photographers (starting with Hatakeyama and Sugimoto, and more recently Lieko Shiga’s Rasen Kaigan series, which I will write about later) and other photographers who cross cultural boundaries (such as the aboriginal artist Christian Thompson: in my work in Australia, starting at the beginning of May, I will be working for part of the time with rural and aboriginal communities, and supporting research projects that have been making images and artefacts). The ‘digital’ turn in my work has brought me in contact with a range of artists exploring time, change, identity and ‘datafication’. I have become particularly interested in posthumanist theory, and artists who are influenced by this. I have explored this in my CRJ, as well as considering the influence on photography and the arts of areas of the humanities, social research and natural sciences (for instance, theories of space and time from theoretical physics). I’ll say more about theory under LO5 (LO3 and LO5 seem to me to overlap in relation to theory). As I am focusing on urban regeneration, there is a strong sociological influence on my work. I hope that through my visual work and writing, I have been able to demonstrate in-depth knowledge and understanding of a diverse range of contemporary (and historical) photographic practice, and to contextualise my work in relation to this and to contemporary theory. The area that I particularly want to develop now is around digitisation, data, social (in)justice and self, and, in particular, the manner in which contemporary desire for data to represent individuals and groups mirrors earlier (thwarted) indexical desires relating to photography.

LO4: Professional Location of Practice.

Over the module I have become clearer about how to position my practice professionally. Coming to better understand the professional contexts for dissemination and consumption of photographic practice has enabled me to clarify both what I do and do not do as a photographer. I am not a professional photographer in any conventional sense: my work is predominantly as part of inter-disciplinary and multi-professional teams, and I want to explore what photography, and arts based approaches more generally, can offer in conducting research into complex questions, and in formulating and implementing actions. My audiences are, therefore, diverse, ranging from the participants in my projects through to academic researchers and policy makers. I am working at all levels from image making with community members through to playing a role in the governance of public bodies. I have come to understand better the dynamics of the fields in which photographers work, and want to actively act as an advocate for a broader vision of what photography can achieve more widely. At this point of time it is necessary, in the face of new imaging technology, software, data analysis, communications, associated social practices and applications of artificial technology to rethink all professions: photographers have to be pro-active in doing this, and to be clear, and confident, about what visual arts can bring to inter-disciplinary work. I’ve explored this elsewhere in the CRJ.

LO5: Critical Analysis.

Having taught social semiotics and cultural sociology, I came to the module with some knowledge of the key critical paradigms and theorists (in particular structuralist and post-structuralists like Barthes, Foucault, Derrida and Lacan, Frankfurt School critical theorists such as Benjamin and Marcuse, and sociologists, such as Bourdieu and Sherry Turkle). My own work has been broadly post-structuralist in approach, with a strong emphasis on language and the analysis of discourse in relation to social practices and the (re)production of social inequalities. My focus in this module has been to better understand posthumanist theory, which takes a more materialist stance and not only de-centres the human subject, but sees humans as materially intertwined and enmeshed in the environment. This gives greater emphasis to neuro- and bio-sciences and to relationships with the environment, objects and other species. Forms of posthumanist theory have been influential in the arts, and where I have explored this in my CRJ, it has been in relation to the work of other photographers. I have also explored areas of contemporary philosophy, for instance Harman’s Object Oriented Ontology and Francois Laruelle’s non-philosophy. Critical appraisal of my own photography and that of other practitioners draws on this work, as well as on perspectives from social research, urban development, environmentalism and cognitive neuroscience, and engagement with the work of other photographers and visual artists. As would be expected from this, I am using photography in a lyrical, analytic and heuristic manner, not as a narrative tool, and therefore have limited expressing opinion on narrative forms of photography (but have written about this in a way that is, I hope, constructively critical about ‘story-telling’). The module has expanded my knowledge of critical theory in photography.

LO6: Written and Oral Communication Skills.

I am confident in my ability to communicate fluently and eloquently in a range of formats and contexts, and to differentiate delivery methods appropriately according to audiences, and hope that my written and visual work, and participation in webinars and face to face activities, demonstrates this. In addition, I am working with community groups and individuals on estates in east London, running photography workshops for undergraduate and postgraduate students and working at board level in the areas of education, urban development and social research, so have to communicate and engage people with my work at a range of levels and in a variety of forms. I’m increasingly confident in using visual modes of communication, and the use of social media. I am based in London, but work internationally, so am able to work collaboratively online, and doing the MA has certainly helped to develop my online communication skills.