Cairns Art Gallery, 16th June 2019

This exhibition forms part of the Cairns Indigenous Art Festival (10th-14th July 2019), and opens officially that week. The exhibition ‘explores the relationships between personal, cultural and national identity in relation to historical and contemporary portrait images by indigenous and non-indigenous artists’. The exhibits are predominantly photographic. In a number of ways, the exhibition takes me back to my first steps in the MA programme, with the engagement with the work of Aboriginal artist Christian Thompson in June 2018.

As the notes to the exhibition state:

‘The concept of portraiture is one that is challenged through works in the exhibition, as it is evident that, for Indigenous peoples, portraiture and identity extend beyond the generally accepted western notion of a vertical representation of a face to depict the image of a person. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, identity and portraiture can be represented and interpreted through a cultural totem, a marking, a foot or hand print, a name or a ritual. It is only in very recent times that photographic portraiture has been available to Indigenous artists, and through this medium they have sought to challenge common perceptions of their identity in order to present images of themselves and others as they want to be seen’.

This resonates very much with the approach I am taking to the use of artefacts, both alongside photographs and in photographs, and the use of the photograph as an artefact. It is important to note, also, that the orientation to photographic images, particularly of people who are dead, varies greatly across different Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) groups. Thompson (whose work, two images from his 2010 King Billy series, is included in this exhibition) adopts a process of ‘spiritual repatriation’, engaging with and producing work as a response to archival images of ATSI people, to avoid the reproduction of these images.

As Lydon (2010) points out, however, some ATSI communities (particularly in South Australia) view these images as a form of Indigenous memory, creating valuable links to a lost past. This contrasts with other groups, notably from remote communities in northern Australia, for whom such images (some of which are featured in this exhibition) would be taboo. Lydon argues that archivists and curators often act, inappropriately, as gate keepers, homogenising Aboriginal culture (in much the same way that colonisers made assumptions about the homogeneity of Aboriginal languages). The point is reinforced by Michael Aird in an essay written to accompany the exhibition.

‘Regardless of how and why photographs were taken, Indigenous people are often able to look past the exploitative nature of some of these images and just accept them as treasured images of family members. To reflect on the way Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people have been represented in photographs, it is often simplified to a story of exploitation – yet, the story is much more complex, with stories of Indigenous people taking control of exactly how they wanted to be represented at different points in time’. [source unknown, quote taken from exhibition notes]

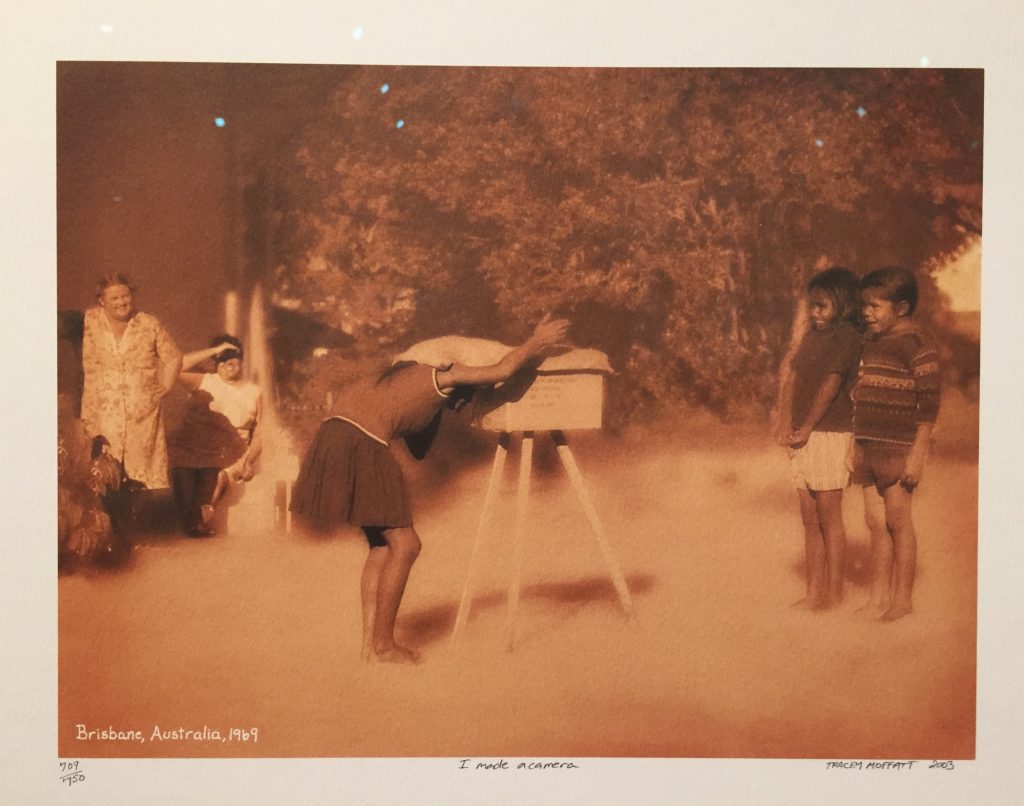

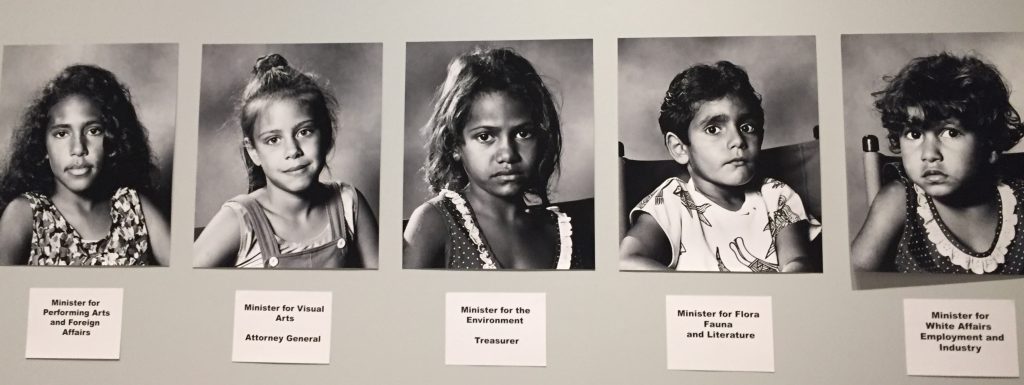

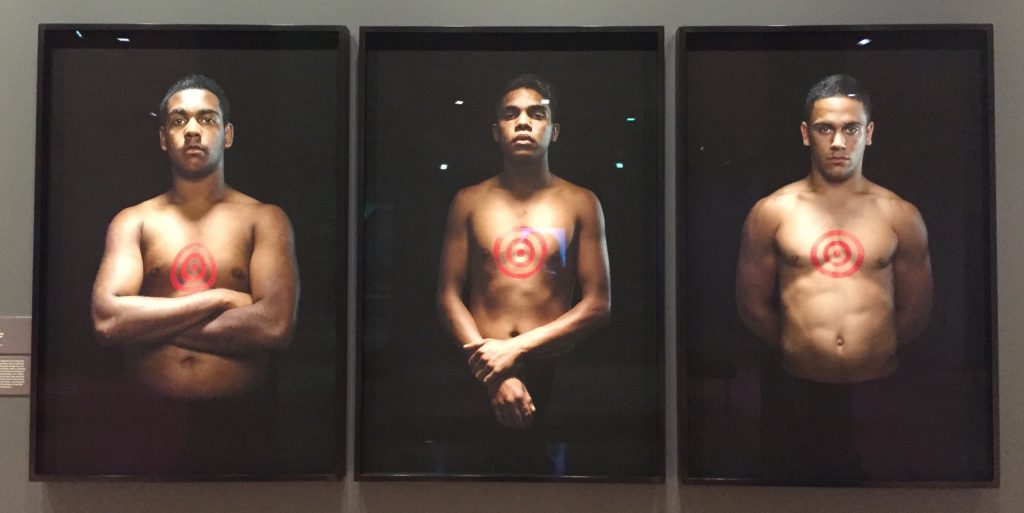

As the exhibition demonstrates, photography can provide a powerful means for the exploration of identity by Aboriginal communities, and, as in a number of exhibits, portraiture, juxtaposed with other images and text, can act as a medium for political comment and activism (for instance, Richard Bell’s 1992 Ministry Kids, Tony Albert’s 2013 series Brothers and Michael Cook’s 2011 series The Mission).

References

Lydon, J. (2010) ‘Return: The photographic archive and technologies of Indigenous memory’, Photographies, 3(2), pp. 173–187.