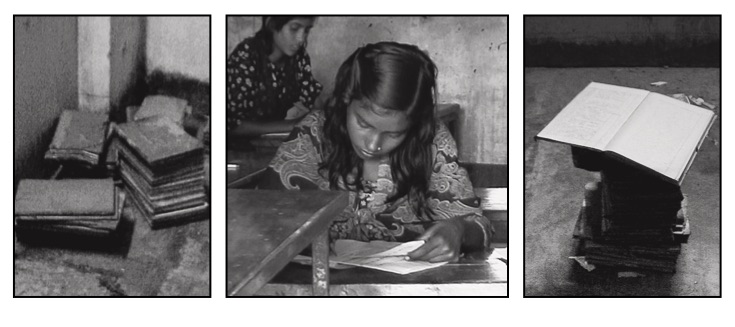

This is the image I have chosen to present (in addition to the ‘re-make’ images) for the Week One online seminar. The photographs were taken in a ‘hard to reach’ school (i.e, one that takes days to get to from the city, and, if it rains, can take much longer to get back from) in 2001 when I was working with the Ministry of Education in Bangladesh. The degraded black and white image makes it difficult to place the photographs in time. The images also have a painterly quality, which challenges the aspiration to mechanical (and now digital) veracity. The activity and objects depicted (books, schoolrooms and literacy practices) also span the history of photography (with mass schooling, based very much around literacy, numeracy and the regulation of behaviour, developing in the UK, through the school boards, from the mid-nineteenth century). Literacy is also particularly important for me; I didn’t learn to read until the age of 8, and when I did, it totally transformed my life, and has shaped my subsequent trajectory. In the case of Bangladesh, and other similar contexts, female schooling and literacy is particularly important. In presenting the images, I wanted to experiment with the triptych format, which invokes an earlier, pre-photographic (and pre-industrial) era in the west.

This is the image I have chosen to present (in addition to the ‘re-make’ images) for the Week One online seminar. The photographs were taken in a ‘hard to reach’ school (i.e, one that takes days to get to from the city, and, if it rains, can take much longer to get back from) in 2001 when I was working with the Ministry of Education in Bangladesh. The degraded black and white image makes it difficult to place the photographs in time. The images also have a painterly quality, which challenges the aspiration to mechanical (and now digital) veracity. The activity and objects depicted (books, schoolrooms and literacy practices) also span the history of photography (with mass schooling, based very much around literacy, numeracy and the regulation of behaviour, developing in the UK, through the school boards, from the mid-nineteenth century). Literacy is also particularly important for me; I didn’t learn to read until the age of 8, and when I did, it totally transformed my life, and has shaped my subsequent trajectory. In the case of Bangladesh, and other similar contexts, female schooling and literacy is particularly important. In presenting the images, I wanted to experiment with the triptych format, which invokes an earlier, pre-photographic (and pre-industrial) era in the west.

Interaction through/with artifacts

I’m thinking about the relationship between the daytime and nightime users, and uses, of the place that I’m exploring (and, of course, the users may be the same people, but with different modes of engagement with the place, different interests and motivations and different relationships with others in that place at that time). One option for exploring this (without direct engagement, which could be highly problematic!) is to create artifacts that are left in the place for others (at another time) to interact with. I’m thinking about environmental artists, like Andy Goldsworthy and Richard Long, who create artifacts in the landscape, and use photography as a way of recording these. Goldsworthy, in particular, recognises, and records, the deterioration/change that takes place in the work (made from objects found in the environment) with the passage of time. In this case, though, I’m thinking about human engagement and agency. So, an artifact is created, photographed and left for a period of time (overnight, and periodically subsequently) to see (and record photographically) how it has changed (or rather, been changed, by humans, animals, weather). This could range between total indifference and total destruction. Worth a try. Need to think about he nature of the artifact and the location. So I think the first steps (photographically) are to explore places within the park where activity and interaction takes place, and to explore the material for making that are available there, and subsequently to work on what can be made. Another option is to leave objects and explore/record their fate (and these activities and interactions leave their own artifacts for other to engage with and respond to, of course). But, I think it is worth figuring out whether making might work initially. Day/night is, of course, just one (extreme) way of differentiating between uses of the same space; this multiplicity of understandings and modes of engagement with the same spaces is a common feature of the increasingly intensive use of urban space. And in research, the use of artifacts to facilitate or provoke interaction and dialogue is well established. I need to explore the degree to which these have been explored photographically, and potential for images that illuminate, engage and provoke.

Christian Thompson, Ritual Intimacy

In a recent trip to Sydney, I went to the Christian Thompson exhibition Ritual Intimacy at the UNSW Gallery. Thompson describes his work as ‘auto-ethnographic’. He features (indeed, is the primary focus of) almost every image (and performance piece) in the exhibition, which explores dimensions of identity and relationship with community, culture and language. As part of his PhD studies at the University of Oxford (he was one of the first two Aboriginal Australians to be admitted in the history of the university) he engaged with a collection of nineteenth century images of Aboriginal people held in the ethnographic collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum. As Marina Warner observes in the exhibition catalogue ‘images of non-Western people were collected as ‘specimens’ rather than as fine art objects or portraits of individuals, and were therefore not assigned to the photography archives at the National Portrait Gallery or the Victoria and Albert Museum’ (Warner, 2017, pp. 64-5). From this, Thompson produced a series of images entitled We Bury Our Own. Wary of re-appropriating, and re-vivifying, the troubling, and fundamentally racist, images, he adopted an approach of ‘spiritual repatriation’, in which he engages with and responds to the artifacts and images held by the museum, without reproducing them. For the Week One task, I chose to re-make the image Danger Will Come, a response by Thompson to a daguerreotype of an Aboriginal man from the 1860s. I have incorporated the current exhibition catalogue showing a plate of Danger Will Come in my image. The re-making, I hope (as best I can in a hotel room), highlights the ironic and paradoxical circulation of contemporary images in the gallery system, and the consequent danger(s) of colonial re-appropriation. In relation to the global images theme of the first week, we have three layers of global image: the initial (unseen by us) objectifying anthropological trophy image, bringing news from distant lands, its spiritual repatriation by an Aboriginal Australian (global) contemporary artist and its pedagogic re-making in a task for an online (international) higher degree programme. There are a number of themes to explore further in the development of my own practice. In relation to my MA project, the relationship of Aboriginal people to the land is clearly important to understand, particularly if I am to explore ‘edgelands’ and ‘non-places’ in Australia as part of this work. More broadly, there are issues relating to auto-ethnography, identity, community and experience to explore, and the fundamental challenge to western conceptions posed by indigenous forms of knowledge.

Christian Thompson, We Bury Our Own [Exhibition], Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 26th June 2012 – 17th February 2013, https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/christianthompson.html (last accessed 5.6.18)

Christian Thompson, Ritual Intimacy [Exhibition], Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, 27th April-8th July 2017, Griffith University Art Gallery, Brisbane, 20th July-23rd September 2017, UNSW Galleries, Sydney, 4th May-28th July 2018.

Warner, M. (2017), ‘Magical Aesthetics’, in Christian Thompson et al, Ritual Intimacy, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne pp. 63-76.

Newcastle Beach Ocean Pool

I work in Newcastle one to two months a year. If I can, I try to swim in the Ocean Pool two or three times a week, usually in the morning. Not possible this year, but I thought I’d take a few photographs after work. The day/night transition was forced – it’s winter and it gets dark at around 6.00 pm. Weather and time allowing, I’ll explore some more. And, maybe, at Mereweather just along the coast – the largest Ocean Pool in the Southern Hemisphere.

Roding Valley Park

This ‘park’ comprises of interconnected, overgrown and largely neglected spaces running alongside and beneath three major roads in East London. Daytime activities are mundane, nighttime activities furtive. A defining feature, and a key challenge in giving a sense of the place, is the noise from the roads, which, resisting visual and material boundaries, sweeps across the surrounding urban areas. My intention is to explore the relationship between visual, audio and textual (re)presentations in conveying a sense of place and the transition/transformation from day to night. Initial images are relatively banal.

A possible direction for development is to place work from this context alongside subsequent studies of similar ‘non-places’ and ‘edgelands’ in other places where I currently work: Singapore (where these spaces are developed by the post-colonial state as ‘green connectors’ for exercise, leisure and urban farming) and Australia (where colonial overwriting of traditional conceptions of land, access and ownership is opposed by Aboriginal communities). The very different conceptions of space of the government in Singapore and Aboriginal people in Australia both present a fundamental challenge to practice and discourse relating to public space in the UK.

Project starting points

A quick reflection on some topics to explore further through my photographic work: ageing, caring, memory, encoding and decoding (particularly in relation the neglect of interpretation in current cognitive approaches in dementia research and practice); collaboration, interactivity and co-production in arts and sciences; new and emerging forms of work and workplaces, and changing relationships with domestic and leisure settings and activities; public/private space and the digitalisation of surveillance; the ambiguity of ‘edgelands’ across cultures; creation of alternative narratives from shared visual, textual and audio resources; countering vulnerability, insecurity and the internalisation of authority through image making.

Singapore Street Portraits

These images are from a 2017 project exploring moments of quiet and introspection in the densely populated high tech city-state of Singapore. Focusing on the busiest central business and retail areas, some also capture moments of anxiety. This was my first attempt at this kind of street portraiture. Whilst instructive, it reinforced my concern about the convert, and potentially dis-empowering and intrusive, nature of this approach. Future work of this kind would be more collaborative. I’m posting these to explore use of galleries in this blogging environment.

First post

I’m not convinced that, in fact, the first cut is the deepest, but certainly the first blog post feels like the toughest (as does the first note in a notebook, or the first paragraph of a essay, or anything that potentially soils an as yet clean page, and which sets a path that can never totally be erased). Anyway, I’m going to use this ‘first post’ to reflect on the transition to being a student. Of course, it’s not transition at all. To an extent, I’ve always been a student. The nature of my work, as an academic, teacher and researcher, places me constantly in the position of a learner (in a positive sense) and (more negatively) as constantly lacking (in the face of the lecture to be prepared, the paper to be written, the data to be analysed, the thesis to be read, the essay to be marked – homework never completed to satisfaction). The dread feeling of not being adequately prepared for what is to come is disconcertingly familiar, as is the counterbalancing excitement of potential engagement with new ways of thinking, experiencing, doing and being. So, not so much a transition to a new identity, but a supplement, and a shifting of the locus of control, risk and uncertainty. The first post sets us off into a forest of unknown unknowns. Should I enable the breadcrumb widget? So much to learn, even before the programme starts. Must be quick to post some more to bury this short text. There’s the motivation.