Exhibition of some of the portraits made with participants and volunteers on the Shed Life project at the Sue Bramley Centre, Barking Thames View Estate. To co-incide with showing of A Northern Soul, and question and answer session with Director, Sean McAllister.

Spacetime and photography

Whilst photography must, in essence, directly address time (in the moment of capture, for instance) and space (in, for instance, the locatedness of the making of the image), addressing the passage of time and spatial difference has been a challenge, without sliding into other forms of (re)presentation (video, for instance). The most obvious strategy is juxtaposition, the bringing together of two or more images that signify difference or transition (in time or space, or perspective, identity, experience or any other differentiating dimension). As Baetens et al (2010) observe ‘Time and space are the yin and yang of photography’ and that ‘The more you press on space, the more the notion of time will return with a vengeance-and vice versa’ (p.vii).

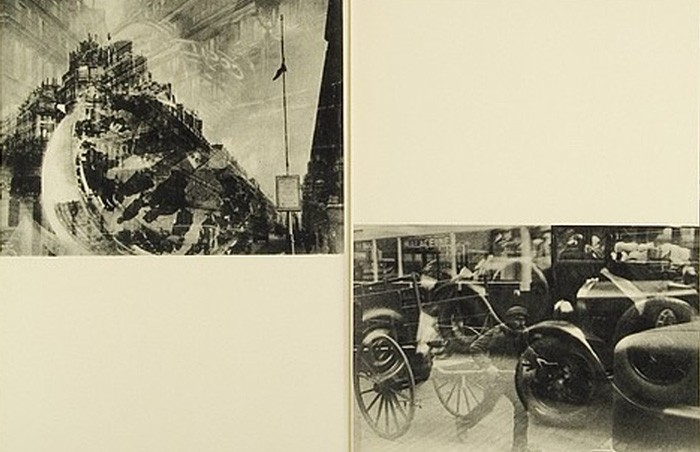

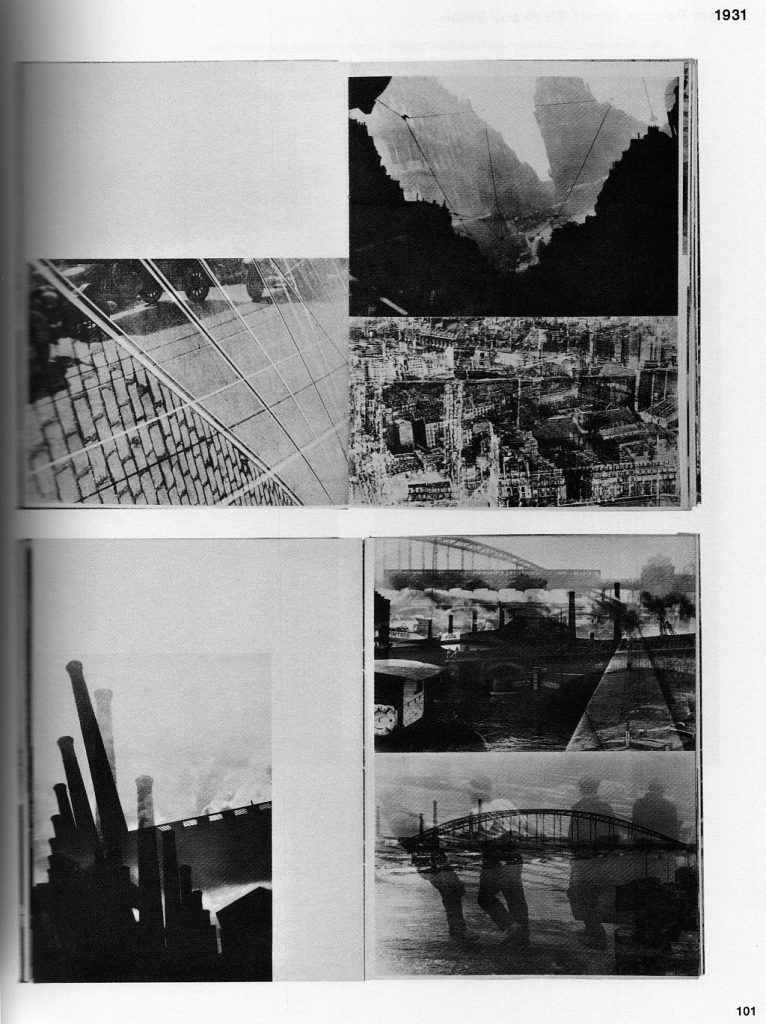

The use of juxtaposition and the layering of photographic images to convey, and disrupt, a sense of time is exemplified by the two 1931 photobooks of Moshe Raviv-Vorobeichic, Wilna and Paris, the latter with an introduction by the Futurist painter Fernand Leger (the Futurists, of course, had a fundamental interest in the representation of movement and the passing of time in the visual arts, including sculpture, painting and photography) . Vorobeichic studied at the Bauhaus, and, in particular, the montages of Paris display the dynamic exploration of relationships, and contradictions, of the modern 20th Century city.

‘The flashlike acts of connecting elements not obviously belonging together. Their constructive relationships, unnoticed before, produce the new result. If the same methodology were used generally in all fields we would have the key to our age – seeing everything in relationship‘. (Moholy-Nagy, L, 1947: 68)

The form taken by Vorobeichic’s Paris montages also meets the challenge issued by Sergei Eisenstein:

‘montage is not an idea composed of successive shots stuck together but an idea that DERIVES from the collision between two shots that are independent of one another …each sequential element is arrayed, not next to the one it follows, but on top of it’ (Eisenstein, 1988a: 163-164).

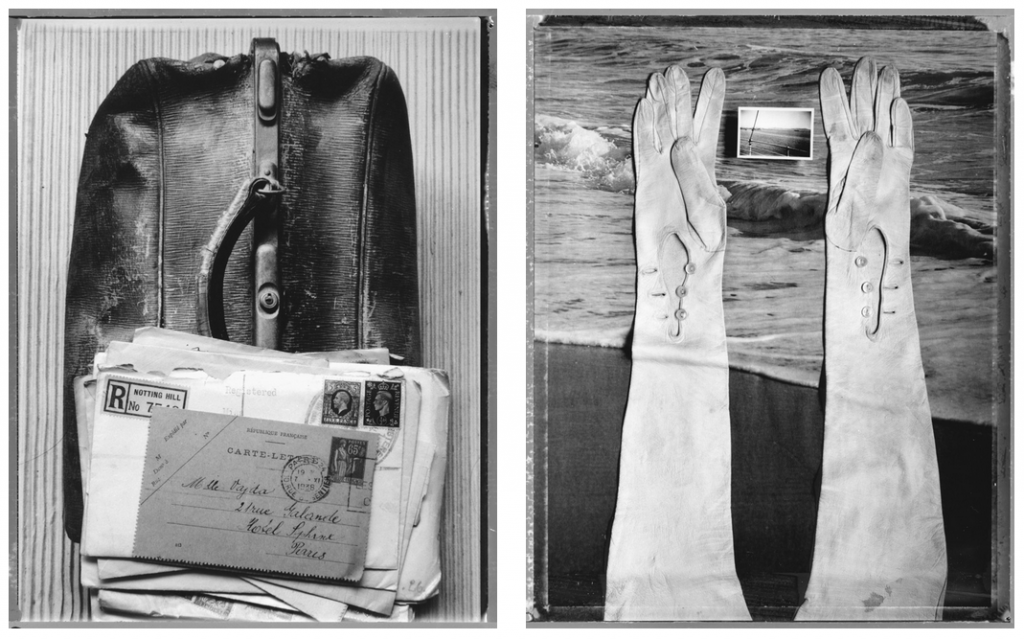

These aspects of Vorobeichic’s work are explored by Nelson (2010). The conception of time in this analysis is strongly influenced by the historical materialism of the Frankfurt School critical theorists, and in particular the writing of Walter Benjamin. Contemporary photographic artists, such as Mari Mahr, continue to work with similar forms of montage and juxtaposition, but extending this to include artifacts and photographs as artifacts (see also earlier post about Peter Kennard’s political photomontage work).

Forbes and McGrath (no date: 2) state that:

‘Mahr’s photographs join the past and the present , the personal and the historical. They might be thought of as ‘”sendings” (envois), which never reach their final destination or reunite with the object or idea they represent (Jacques Derrida cited in Jay, 1993)’.

Whilst I am also attempting to engage with challenge of incorporating a sense of time in my work, I am doing so in the context of contemporary scientific notions of time and a re-configuring of the humanities and social sciences in post-humanist theory (see Hayles, 2018, for an exploration of the relationship between contemporary science and humanities, and in particular the influence of notions of chaos). A key characteristic of current theories of time in physics is that they depart dramatically from our common sense notions and human experience of time. This is explored by Grace Weir in her installation Time Tries All Things at the Institute of Physics in London.

This is a dual channel video work, with accompanying sculpture, in which two theoretical physicists explore contrasting ways in which general relativity and quantum theory can be brought together in understanding spacetime (a term which reinforces the assertion that, in contemporary physics, no conceptual distinction can be made between space and time).

Dowker (2019), in the exhibition catalogue, states that:

‘On the subject of “time”, however, there is not consensus on whether our perceptions can be coordinated with our current best scientific world view. We perceive time passing and make sense of our lives within the context of a fixed past that has happened and an open future that hasn’t happened yet. But the dominant view amongst theoretical physicists is that the Universe is a Block in which the future already exists and time doesn’t pass.’ [no page]

She adds that to seek alternative ways of thinking about spacetime ‘requires new thinking along lines we probably can’t foresee. How do we break out of old ways of thinking and create new knowledge that yet remains disciplined by and true to all that we already know? We need to understand our current best theories , General Relativity and quantum theory, as well as we can … We can also look to art, music and literature to inspire and to challenge.’ [no page]

The departure from human perception of time acts to de-centre the human subject in much the same way as post-humanist theory (and, in a more extreme form, object oriented ontology or speculative realism). In my own image making, I want to attempt to subvert an assumed directionality in time. Global development is intertwined but not co-terminal with human development, and tensions between the natural and the built environment, and human activity within these environments, entail interdependency, indeterminancy and precariousness. An appropriate visual strategy has to incorporate this, and should find a way to explore interactions between and within spacetime. If there are layers and juxtapositions of images, these have to interact and influence each other, ether within the image or in the mode of presentation of the work. The mixing of images that I am exploring produces new images in which the different channels interact. The images are complex, and care has to be taken to make them accessible to an audience, both through the construction of the images, and how they are presented (in themselves and alongside other forms of images, media and artifacts). I’ll explore this in another post.

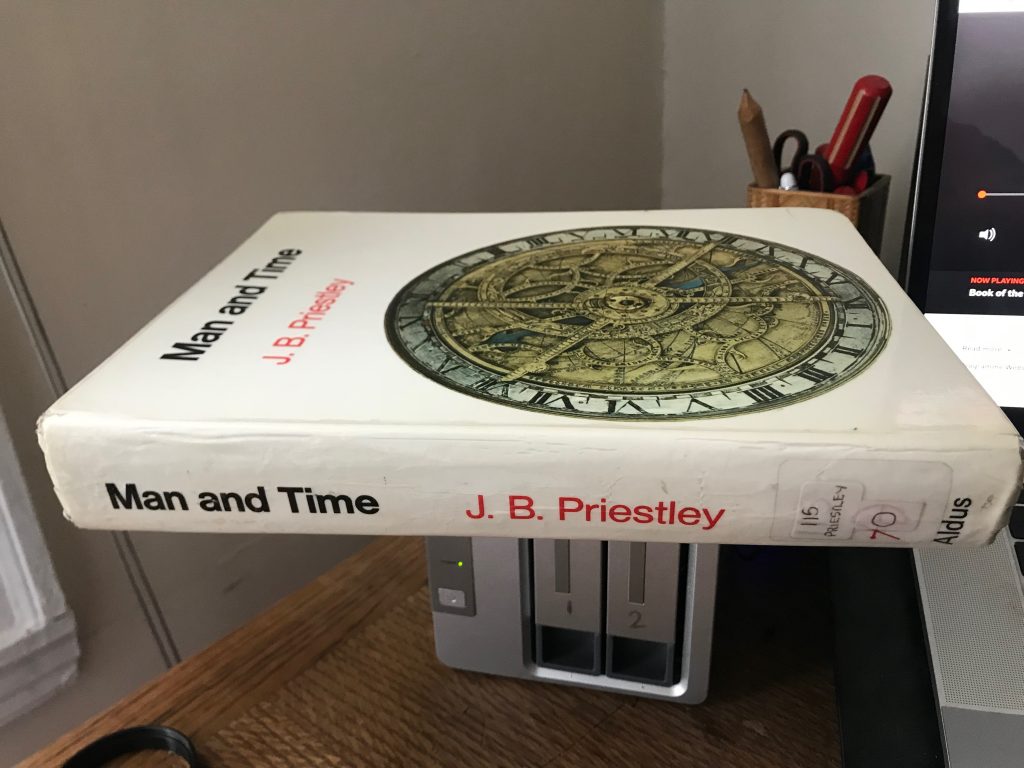

As with other aspects of my development as a photographer, there is a personal dimension to taking this direction. I failed to learn to read at infant school and was a ‘remedial reader’ in junior school (more on this another time). My way into literacy was through Marvel comic books (I had a bike and did paper rounds from the age of 9, getting paid double by the newsagent if I took payment in comics). I read these obsessively, and when I’d started to get the hang of the text, I transferred this obsession to the local library, where I read my way through the junior library, and then at the age of eleven, I moved over to the adult library, and worked my way through using the Dewey decimal system as a guide (in classic autodidact style). The first section, after General Reference, is Philosophy, Psychology and Logic (100-199) so I have a really good grounding in these areas. One particularly influential book was J.B. Priestley’s (1964) dubiously titled Man and Time (115 in the Dewey decimal system), which explored different conceptions of time in science and the arts (my wife bought a copy of this on eBay a few years ago, and strangely it turned out to be from Barking and Dagenham library).

I went to university to study theoretical physics, but dropped out in the first term, and went to work as a kitchen porter and bingo caller before returning to university later to study education with mathematics and psychology.

Two other co-incidences. There is a programme on bingo calling on the radio as I write this. And, as I watched Grace Weir’s video installation, shortly after she walked across the screen, the door opened and she walked into the gallery (only me and one other person there), took some iPhone photos, watched 5 minutes of the film, and left.

References

Baetens, J., Streitberger, A., and Van Gelder, H. (eds). 2010. Time and Photography. Leuven Univeristy Press

Dowker, F. 2019. Becoming. In catalogue to Time Tries All Things, installation by Grace Weir, Institute of Physics, London. 21.01.19-29.03.19. [no page]

Eisenstein, S. 1988. ‘The Fourth Dimension in Cinema (1929)’, in Taylor, R. (ed.) Eisenstein Selected Works, Volume One, Writings 1922-1934. London: BFI Press, pp. 181–194.

Forbes, D. and McGrath. R. [no date]. Mari Mahr. London: Architectural Association. [Available at http://marimahr.com/reviews/index.html]

Hayles, N. K. 2018. Chaos Bound: Orderly Disorder in Contemporary Literature and Science. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Jay, M. 1993. Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth Century French Thought. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Moholy-Nagy, L. 1947. Vision in Motion. Chicago: Paul Theobald.

Nelson, A. 2010. ‘Suspended relationships: the montage photography books of Moshe Raviv Vorobeichic’, in Baetens, J., Streitberger, A., and Van Gelder, H. (eds) Time and Photography. Leuven Univeristy Press, pp. 141–164.

Priestley, J.B. 1964. Man and Time. London: Aldus Books.

Vorobeichic, M.R. 1931. Ein Ghetto in Osten (Wilma). Schaubücher 27. Zurich/Leipzig: Orell Füssli Verlag.

Vorobeichic, M.R [Moi Ver]. 1931. Paris. Paris: Éditions Jean Walter.

Channel mixing process

I’m working on a protocol to follow for the production of images in the different settings I’m exploring using the channel mixing approach. For the moment I am going to focus on monochrome images (colour would, in this method, be artifactual in any case – I’ll post something about this later, as it relates to the nature of digital, as opposed to analogue, images, and to contemporary debates in the philosophy of photography). In each setting I will produce three images which vary with respect to time (either through connotation, or by incorporating archival images of the past and CGIs or sketches of a projected future). The images will also explore other relationships, for instance between the natural and the built environment. Whereas photomontage and other photographic techniques layer or juxtapose images, channel mixing creates an interaction between the images which is not simply additive or subtractive, thus better reflecting contemporary notions of the relationship between space/place and time. Small changes in the prioritisation of particular tones in specific channels can create very different (but clearly related) images (as in the examples here). Whilst I want to retain a degree of chance, I also want to be clearer about the kind of images that will work best together to get the effects that I want in invoking the different relationships between communities and regeneration that I have identified. To that end, I’m experimenting with the process with some relatively simple images.

The process I have followed here is to take the following photographic image and create three images by horizontal translation (so each is a slightly offset version of the other).

The images are assigned to the red, green and blue channels in Photoshop respectively. Using a monochrome conversion layer, different composite images can be created by different mixes of the channels. To get a sense of how the channels interact, I produced four images and combined them in an animation. It works best in full screen mode.

Next step is to work with more complex images, and then, once I have a better sense of how the mixing process shapes the resulting image, with images produced in each of the settings.

Project Development (Week 7 Reflection)

No formal task for the reflection this week, so I’ll just briefly reflect on the development of my work over the past week and point to other relevant posts. I have posted reflections on the portfolio reviews and the skills building workshops at the Falmouth Face to Face.

The former were really useful in reflecting on my current work, how I will develop this over the next module (Surfaces and Strategies, with a focus on different ways of presenting and making images material) and how to prepare (in terms of development of my practice) for the FMP. The latter helped me to develop skills in producing, processing and presenting images, and get to know other participants and tutors on the programme. I have written about The Living Image conference and how the themes addressed relate to the development of my own work here.

Over the past week I have been able to develop my thinking and practice in relation to a number of the issues raised last week. Time and the archive have been major themes. The Moving Objects Symposium raised questions about the place of the archive in the life of displaced communities, including those in refugee camps, and highlighted the role that the creative arts, and arts based methods, can play in understanding and empowering communities. More detailed consideration of this, and the Moving Objects: Stories of Displacement exhibition are posted here. I also went to the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2019 shortlist exhibition (reflections on that are here) and Grace Weir’s installation Time Tries All Things at the Institute of Physics (reflections on that here, in relation to the theme of spacetime and photography). I also took part in the London Prosperity Board Prosperity Index Users Group workshop at the Institute for Global Prosperity, which provided a good opportunity to strengthen links with with community and local authority stakeholders around the Olympic Park and in Barking and Dagenham, which I will need for my FMP, and to help shape the use of the Index in east London.

The major development in relation to my own work was studying the work of Moshe Raviv Vorobeichic, and in particular how he deals with time through photomontage in his two 1931 photo-books, Wilna and Paris (see discussion of this work in Nelson, 2010).

It was good to discuss this in relation to my own composite images with Michelle at the 1 to 1, and I’ll develop this further. In particular, I want to consider how I can juxtapose images with the composites (we decided that to put the constituent images alongside the composites would be distracting). In response to developments in contemporary understandings of spacetime, I am also thinking about pulling out smaller sections of the composites (a technique that was also used by Vorobeichic).

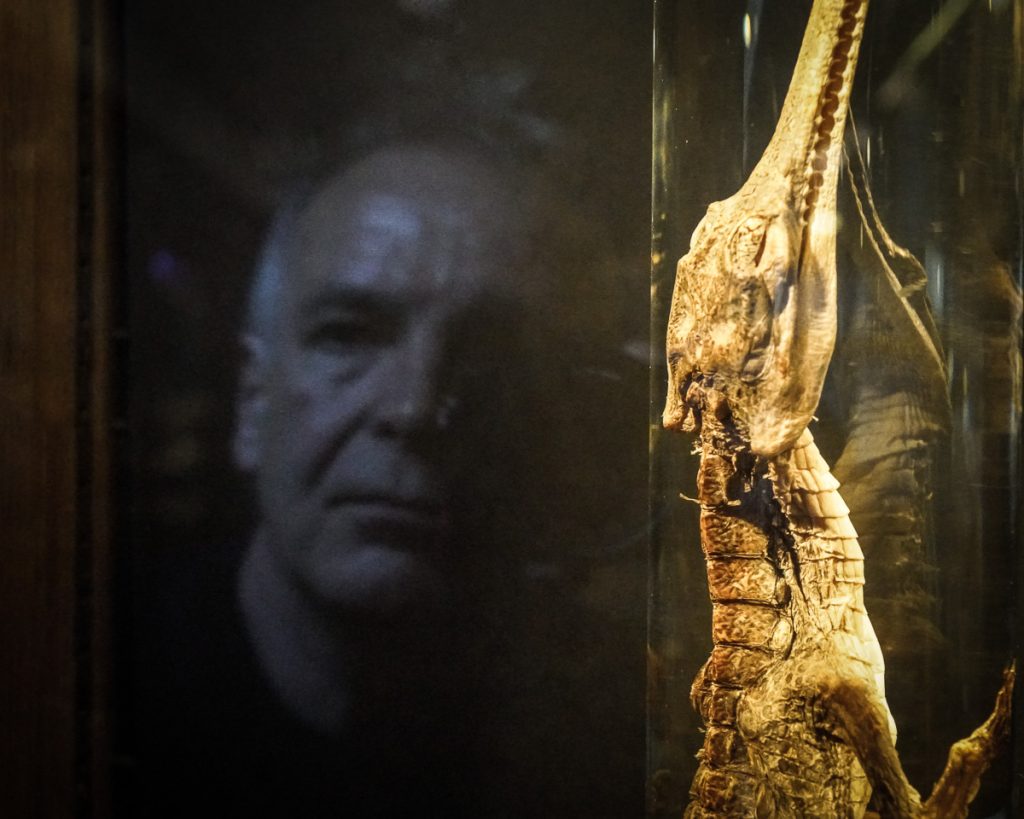

In relation to practical image-making, I attended a session on the ethics of exhibiting human body parts and spent half a day with students at the UCL Pathology Collection, photographing items from the collection that they will use in their presentations next week.

This collection is not open to the public. I have spoken to the curator about the possibility of working with the collection in producing artistic work, and she is keen to do this.

I’ll follow up, and could possibility use this as a focus for the activities and portfolio work for the Surfaces and Strategies module.

References

Nelson, A. 2010. ‘Suspended relationships: the montage photography books of Moshe Raviv Vorobeichic’, in Baetens, J., Streitberger, A., and Van Gelder, H. (eds), Time and Photography. Leuven Univeristy Press, pp. 141–164.

Vorobeichic, M.R. 1931. Ein Ghetto in Osten (Wilma). Schaubücher 27. Zurich/Leipzig: Orell Füssli Verlag.

Vorobeichic, M.R [Moi Ver]. 1931. Paris. Paris: Éditions Jean Walter.

Exhibitions

Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2019 shortlist. The Photographers Gallery, London.

Moving Objects: Stories of Displacement. UCL Octagon Gallery, London.

Time Tries All Things, installation by Grace Weir, Institute of Physics, London.

Conference: The Living Image.

9th-10th March 2019, Falmouth University, Institute of Photography

A great opportunity to get to know the work of the tutors better, and hear from students in the later stages of their work. Plus three stimulating presentations online from the USA. I’ll need to revisit this on Canvas, so just sketchy notes at this point, particularly in relation to development of my own work.

Jesse. Offered us a virus metaphor and explored Dawkins’ idea of the body as a vessel for genes, and the passage of the meme (as learnt memory gene). Raised issues for me around the toxicity of analogue photographic processes (related to the pollution around the former chemical plants on Barking marshes) and the vulnerability of the photographic print (and the print as artifact, which resonates with my current work with prints).

Stella. Exploration of hybrid photographic processes (eg. 3D in photoshop, alignment of fine art and commercial photography, combination of analogue and digital (could use this as part of the narrative around Barking marshes in relation to the passage from material to symbolic production, and from analogue to digital photography). Traced the emergence of New Media Arts and changes in the production and distribution of art in the 1980s. Follow up her paper on moire effects and errors, and the idea of asignifying semiotics. Also Hito Steyerl’s ‘How not to be seen‘. See notebook for others.

Paul. Frank exploration of his own biography and the photographic exploration of Blake’s passage along Stane Street. Great images, including shots from the annual Blake graveside gathering.

Michelle. Traced her pathway into photography and interest in sub-cultures and people on the margins. Interesting work on body-change, fragility and transition from childhood to adulthood. Check out 2006 monograph. And Multistory in West Bromwich for art projects.

Katerina. Traced through her MA work on moth trapping. Made reference to post-humanist theory and de-centring. Interesting array of outputs from the project: prints, archives, a small book. Interesting video of stills with music.

Gary. Good insight into his own work and re-photography more generally. Check screenshots from forthcoming book. Interesting exploration of work on Flickr and Instagram. See notes. Check Kedra, 2018, What does it mean to be visually literate, Journal of Visual Literacy, 37(2):81.

Clare. Re-enactment, memory and critique. Ref to Benjamin and Deleuze, and to the work of Jo Spence.

Karen. Short videos. Interviews, and adapts methodology to subject and collaborator. Explores physical space in relation to psychological sense of self. Seeks to use material in an informative and compassionate way.

Cemre. Photographs as objects. Explores how photographs play a part in intimate relationships. See Milktooth and Lohusa films on Vimeo. Double portraits without presence of either (eg umbilical cord as representing a relationship) – links with object related work. Explores changing roles and relationships in ageing. Check filbooks.net.

Mark Klett & Byron Woolf. Traced development of their work from survey to more creative exploration. Look at Drowned River (2018) with Rebecca Solnit. Overlaying of images. Now working in digital. Used portable printer in field to produce in situ panoramas. See notes for references.

Charlotte Cotton. Explored background and follow up to Public, Private, Secret at ICP, New York. Noted oblique approach to surveillance. Reference to alterity and othering. Check Zuboff on surveillance capitalism.

FMP candidates. Really interesting and useful insight. Will incorporate into later posting on FMP.

Chris Coekin & Noel Nasr. The Distance is Always Other. Insight into the process of development of the project. Check out book published by Dongola Press. Good on the development of a ‘visual strategy’ (and relationship with temporal and cultural shifts though re-photograph and dual image making). Strong rationale given for the combination of images taken by Noel and Chris at the same time with the same type of camera and film (relating to photographers from different cultural backgrounds addressing the same scene).

Also insight into how they incorporated sound (including field recordings). Noel’s earlier work also interesting in the use of archive material, printed over his images of scenes of assassination in white ink).

Falmouth F2F Portfolio Reviews

I took part in three reviews. In each case I focused on the more experimental channel mixing work, to get some feedback on this and how I might develop it. I got useful comments from each session, and will think through how to respond to these constructively.

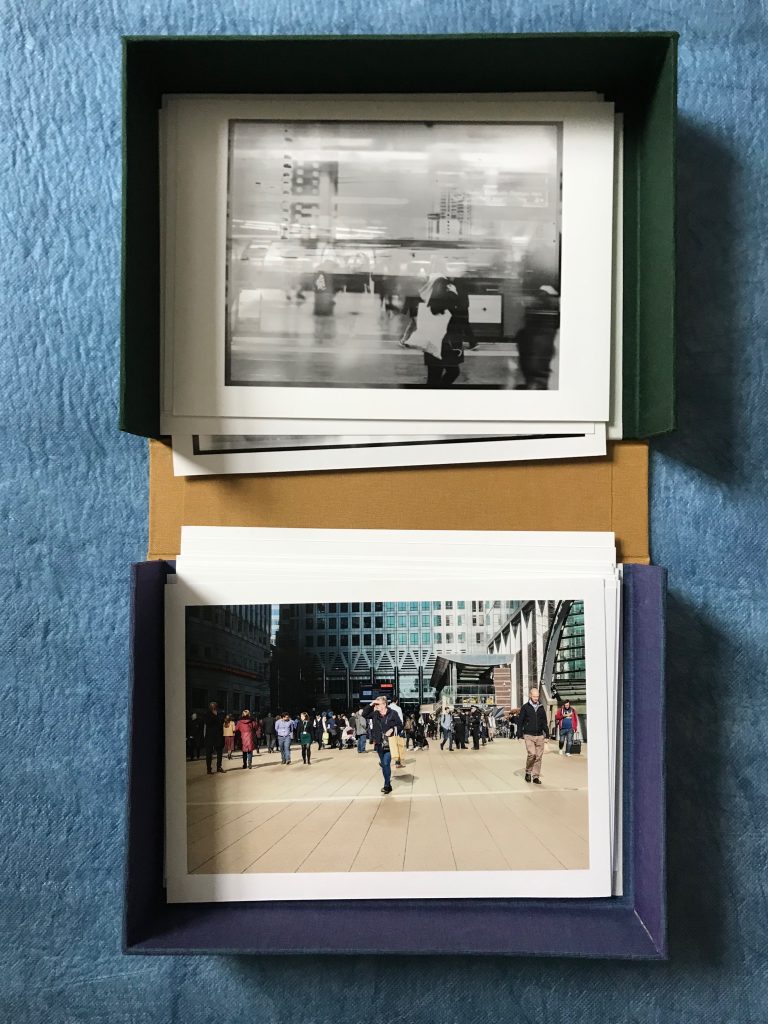

(i) Gary, Katerina and Clare. The focus in this session was on how to present the range of outputs from the regeneration work. Clare suggested a website. Gary suggested something more like an archive, which has physical presence, and whilst more difficult to access, is more difficult to destroy. My thoughts are that it might be possible to produce something that can be configured by others in different ways (according to their interest in the work). This resonates with my thoughts about using photography as a heuristic device (whilst critiques of the photography as representation abound, the alternatives proposed are either performative or introspective: photography as a heuristic offers a more social and potentially transformative alternative). Gary’s observation was prompted by my use of the archive box I made a London Book Arts, and I could certainly make a number of these in which to present prints (and this links with my focus on prints as artifacts). I’m also still considering handmade books. I need to look again at Christian Boltanski‘s work (I have one of the boxes he produced for the Whitechapel exhibition in the 80s). Other artists to follow up: Taryn Simon (suggested by Katerina), Andrea Luka Zimmerman (Haggerston Estate work, suggested by Clare), Mary Evans (on archives, suggested by Gary) and Mat Collishaw (suggested by all). We also discussed Forensic Architecture’s Turner Prize installation (see also my earlier post on the Turner Prize shortlist) and the use of timelines and time-codes. The overlaying of a map with historical settlements also holds potential for my work, I think. Could chart changes of use in the area over time, and link to other images and documents. This also links with the work with JustMap creating a community map of the Barking Riverside area.

(ii) Steff and Michelle. I wanted to think about the form and content of my WIP portfolio in this session. Comments received reinforced the need to focus more tightly on a particular part of the project. Reflection on this has strengthened my commitment to focussing on the level of my own creative work produced in response to the my experiences and work in regeneration areas. I need to make sure that the intent in making these more experimental images is clear (there is a strong expectation, I think, that photographic work in these contexts should take a particular form, as explored in my earlier oral presentations). I think there is also a concern about the complexity of the images. Michelle expressed concern about the descriptiveness of the images and lack of clarity about what I wanted the viewer to feel, for instance, was the intention to present a dystopian or apocalyptic vision. She suggested zooming in on a parts of the image (maybe those where there is ambiguity) and consideration of the political dimensions of Robert Rauschenberg’s work (also, complexity). And another recommendation to look at Taryn Simon, as well as John Stezaker (collage, and complex images) and Brian Griffin (for instance, The Black Kingdom). The images presented are just exploration of process at this stage, so useful to think through this issue now, which I will do in a later post. If I continue with the channel mixing idea, I need to think about whether (and if so, how) the constituent images are presented alongside the ‘mix’ (or mixes), also discussed in this session. It is also possible to animate the mixes, bringing particular aspects of the image to the fore, which could address the concern about the focus of the image (which would change as the interaction between the images changes). And I could incorporate sound, as with the Roding Valley Park work. Others in the group agreed that the images might work best if printed large.

(iii) Wendy and Stella. I wanted to look forward to the FMP stage in this session. Wendy’s comments helped me to be more confident in the research dimension of the assessment of the FMP, and reinforced the the need to ensure that this was clearly articulated with the image making. We discussed the possibility of printing the images on perspex (or on acetate) as another way of invoking interaction between the images. Stella was concerned about the arbitrariness of the colour aspects of the channel mixing approach, which worries me too and which leaves me with monochrome images. I think that is fine, but I need to work through the rationale and effects of the process, perhaps in relation to the production of ‘fictions’ that project backwards and forwards from a point in time (to a constructed past and an imagined future). Am looking at Stella’s paper on Moire. Wendy confirmed that not all the work presented in the FMP has to be done in the two semesters, for instance, where the project is longer term and developing over the course of the programme. There must, however, be significant value added to the project over the course of the FMP (it can’t, for instance, be an existing body of work that is ‘tweaked’ in the FMP). The presentations by current FMP students at the conference were particularly useful in seeing how the FMP could develop.

Falmouth F2F Workshops

Really useful to get to know the facilities at the Institute of Photography, and to figure out how to make best use of what’s on offer when I visit again in the future to work on my FMP. The workshop helped to build skills in particular areas:

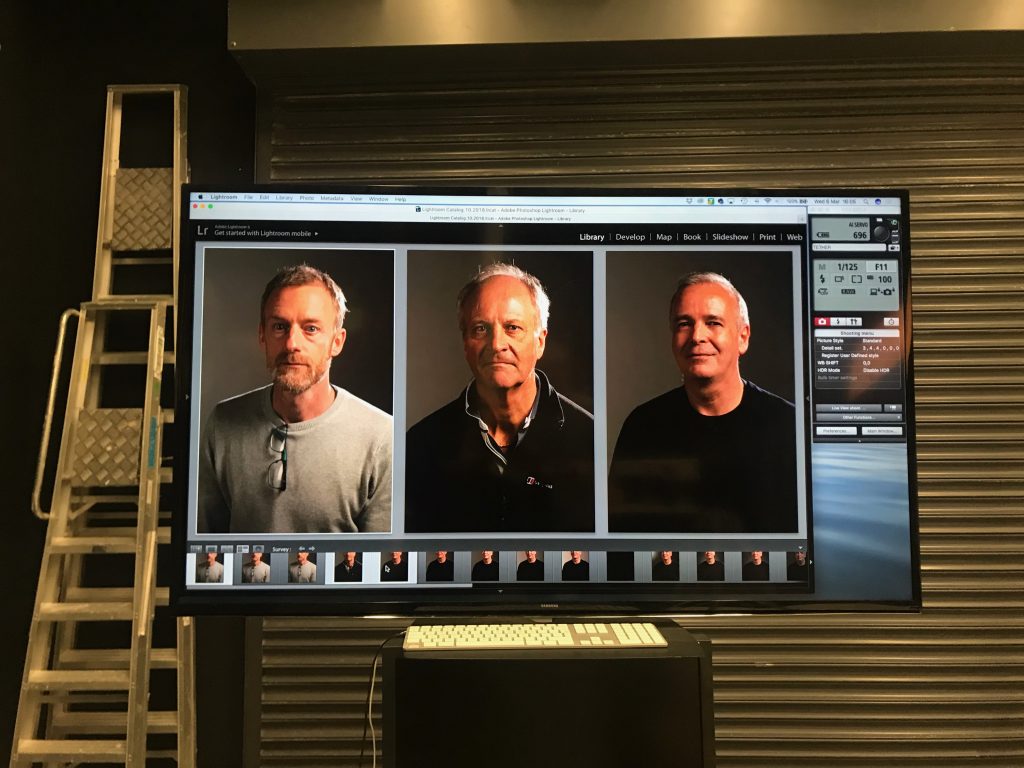

(i) Medium format digital. Got to know the Capture One software (similar in most respects to Lightroom) and work with the Mamiya/Leaf system in tethered mode. It would be good to hire a medium format system for the Object Lessons work in the UCL Museums, Collections and Galleries

(ii) Studio lighting. Great afternoon with Matt Jessop and fellow student Len Williamson. I have done a studio lighting course before. This gave me the opportunity to experiment with lighting and get immediate feedback by making images tethered to Lightroom (again, a new experience for me). See headshots below. My own work is in the field, but it was useful to be able to play around in a ‘controlled environment’, and this will certainly help me in the lighting design for the Object Lessons work, and for the portraits for the urban regeneration project.

(iii) Machine processing. I shoot on film from time to time. Good to learn to use the machines. However, as I think through my major project, I think there are environmental issues to consider in using film (particularly given that parts of Barking marshes are heavily polluted by the chemical plants that used to be there (and this is increasingly of concern as the use of the surrounding land switches from industry to housing).

(iv) Film scanning. As for machine processing, good to be able to use the Hasselblad scanners, particularly for my large format negatives.

(v) Preparing for print. A refresh rather than something new. Useful for getting to know the print service at Falmouth, and how to produce files specifically for that. Also helpful in thinking about file naming of outputs for web and print (which is pretty random for me at the moment). Will follow up advice on colour management at theprintspace.co.uk and tutorials on software at lynda.com

Together this made a fairly coherent package. I certainly feel more confident in planning to spend some time at the IoP in the future, and its good to get to know the academic and technical staff, and to work alongside fellow MA students.

Ideology and Photography (Week 6 Reflection)

The independent reflection task for this week asks us to consider whether our practice may or may not be seen as adhering to a specific ideology. In the creative process, ideology will influence both the production of our work (through the intent that informs the work, and the conceptual frameworks that underpin this) and its interpretation (through the systems of ideas that inform our audience in their reading and the contexts within which they encounter our images). The means by which our work is circulated and reaches an audience (via social media, or the gallery system, for instance) is also shaped by ideology. For instance, we produce and distribute our work in a period that is politically and economically grounded in neo-liberalism and increasingly subject to the push and pull of popularism, which will influence the nature of the means of distribution and the value attributed to the work in different contexts and by different groups and communities. Whilst recognition that production, consumption and circulation of photographic images is ideologically infused is necessary, we can adopt a critical or oppositional position in our work. In doing so, it is important to be clear that this will involve contestation: we need to have a sense of what we stand for and what we stand against, and the consequences of this. My own work seeks to create or provoke different ways of thinking about social and environmental phenomena. It is inherently critical of both current practices in urban regeneration (adopting the view, as expressed by Jane Jacobs, 1961, that ‘Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody’) and some forms of contemporary theory and discourse in the arts (through, for instance, critical engagement with the idea of the anthropocene (see Demos, 2017), and the influence of object oriented ontology, (see, for instance, Harman, 2010, and critical commentary by Lemke, 2017.) How this impacts on the reception and reading of this work depends on the form of the audience and the context of engagement. Whilst the work is theoretically informed, and positioned, engagement with theory is not a prerequisite for reading and understanding the work. The work is intended to be accessible to anyone interested in issues relating to community involvement in urban regeneration and those interested in contemporary arts. The ensuing dialogue, in turn, leads to further development of the work.

Power relations are inherent in all levels of the work, from initial engagement with communities through to the circulation of the work, as is the commitment to ethical practice. I will expand on this, and how my practice relates to other practice and theory in the visual arts, in subsequent discussion of the development of my project and my work in progress portfolio, which will focus on the more political aspects of the regeneration project and more experimental form of photography.

References

Demos, T. J. 2017. Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Harman, G. 2010. Towards speculative realism: Essays and lectures. Winchester: Zero Books.

Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Lemke, Thomas. 2017. Materialism Without Matter: The Recurrence of Subjectivism in Object-Oriented Ontology. Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory. 18: 133-152.

March 2019 Project Update

A quick catch up on where I am, in practical terms, with the various strands of my project.

1. Community engagement with urban regeneration

This is the focus of my research proposal for the FMP. Building networks, contacts and relationships is core to the development of the work. This is focusing on two areas.

(i) Barking and Dagenham.

I have been making images to feed into an image bank for the Thames Ward Community Project (TWCP). My images of the Barking Riverside development were used in a presentation at the recent TWCP summit (at which the CEO of the development company, the Bishop of Barking, a local headteacher, the leader of the residents association and the local councilor spoke). I took photographs of the event and have added these to the TWCP repository. This contributes to the component of the project concerned with collaborative creation of images for advocacy.

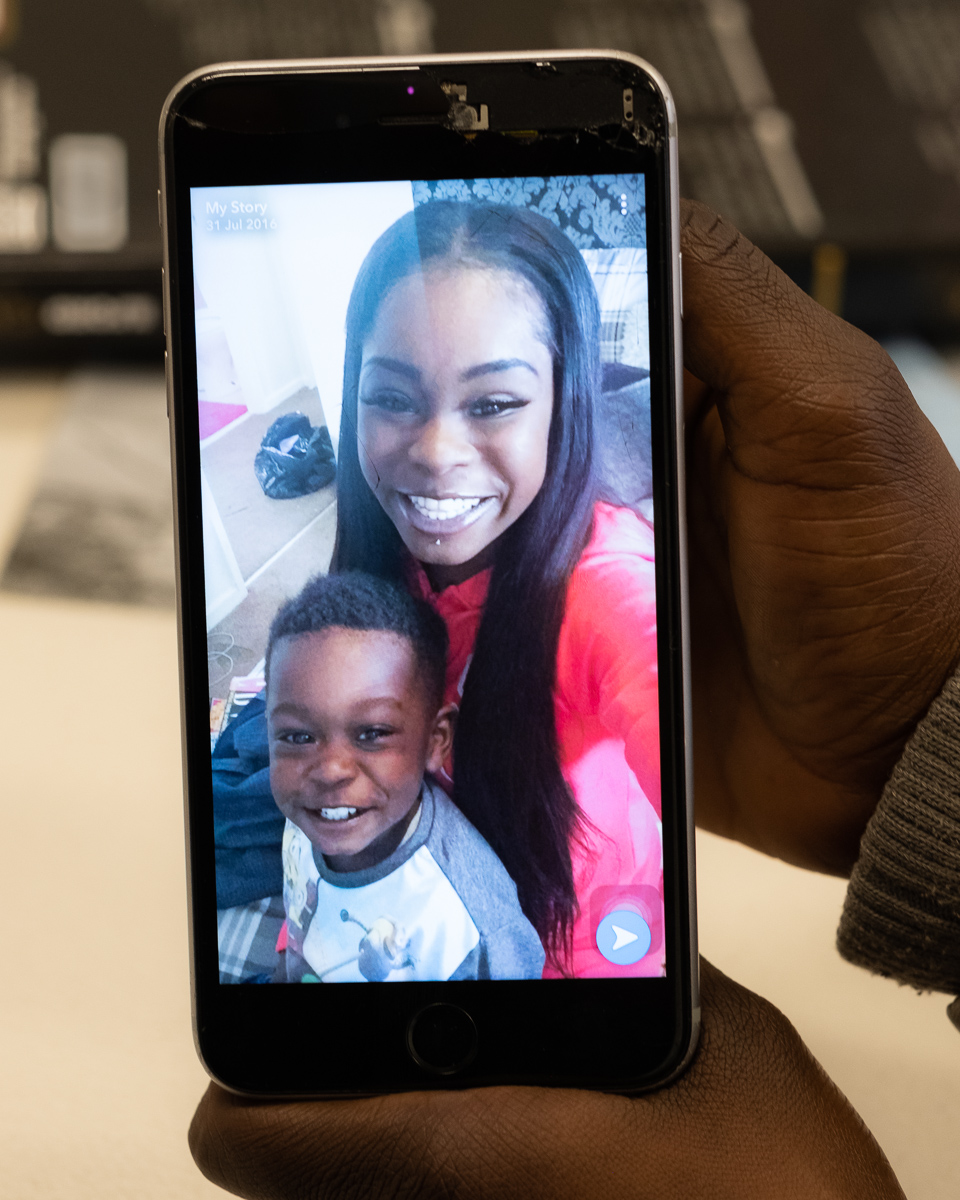

I am working with a local arts project (ShedLife), and have an exhibition of portraits and other images of the participants to accompany a showing of the film ‘A Northern Soul’ and Q&A with the filmmaker (Sean McAllister) at the project on 27th March. The project also involves supporting young adults who are documenting the process and working with participants’ photographs and their own image making, which contributes to the component of the project concerned with working with images to gain mutual insight into and understanding of the lifeworlds of the residents.

Through the project, I am now also in touch with the Barking Creekmouth Preservation Society, the Barking Heritage Group, Thames View Community Gardeners and residents on the Gascoigne Estate. The work in Barking has contributed to the development of all three levels of my project work, and provides lots of opportunities for development at the FMP stage. I also want to open up the use of the local authority archives at Valence House and the use of images in community mapping by JustMap.

(ii) Stratford Olympic Park.

In addition to being a member of the London Prosperity Board, I am now an invited member of the EAST Education Leadership Group. This gives me direct insight into and involvement with the development of initiatives on and around the Olympic Park. In relation to image making, I am putting this on hold for the moment. I’ll continue to form links and networks to keep open the option to carry out the final project in this area. Chairing discussions at the Creating Connections East meetings has helped me to form links with community groups across the four boroughs surrounding the Olympic Park. I’ve also met with people on the Carpenters Estate through the ESRC Displacement Project, and with people organising arts related aspects of the project (principally to ensure that there is no confusion between my own work on the estates and their work – I’ll write more about community arts initiatives related to research and to urban development in a later post).

2. Object Lessons

I’ve continued to attend the weekly lectures and take part in the workshops. The students are now working in groups to produce online exhibitions based around different kinds of objects. They will present these at an all-day workshop on 22nd March. I have spoken to the course team about making images with the students and their objects in the various collections participating in the programme. The major contribution to my work, however, has been the focus of the programme on objects, which fits with the more materialist turn in my own work, and interest in artists like Cornelia Parker, and writers such as Peter Stallybrass (for example, Stallybrass, 1998) concerned with memory and materiality (see, in particular, Freeman, Nienass & Daneill, 2016). The programme has focused on the narratives that can be created around objects, and the value of objects in well-being and therapy (Solway et al, 2017). There is also, however, a growing contemporary theoretical interest in the disruptive and obstructive function of objects, and our projection of agency into the material world, creating ‘uncanny objects’ with an apparent agency and insistence, and resistance, of their own.

I am thinking about ways of using the collections, for instance the zoological collection at the Grant Museum (created to provide ‘artifacts’ for teaching and research in the Nineteenth Century but fulfilling a very different function now) in exploring these issues, and the role played by the collections in the emergence of eugenics and other oppressive regimes of thought.

The ‘uncanny object’ in a later era is explored by Lisa Mullen (2019), in ‘Mid-century Gothic’.

‘Mid-Century Gothic defines a distinct post-war literary and cultural moment in Britain, lasting ten years from 1945-55. This was a decade haunted by the trauma of fascism and war, but equally uneasy about the new norms of peacetime and the resurgence of commodity culture. As old assumptions about the primacy of the human subject became increasingly uneasy, culture answered with gothic narratives that reflected two troubling qualities of the new objects of modernity: their uncannily autonomous agency, and their disquieting intimacy with the reified human body’.

This opens up new visual possibilities in exploring the relationship between the students and the objects they have studied.

This work has influenced all other aspects of my photographic work, and, in particular, treatment of images, in print form (and also, maybe, in materialised form on a smartphone screen), as material objects. In the other projects I am exploring this, and the form that my own ‘images’ will take, and how they will be circulated and encountered (for instance, made material as different kinds of prints, as books, as artifacts, in exhibition space and so on).

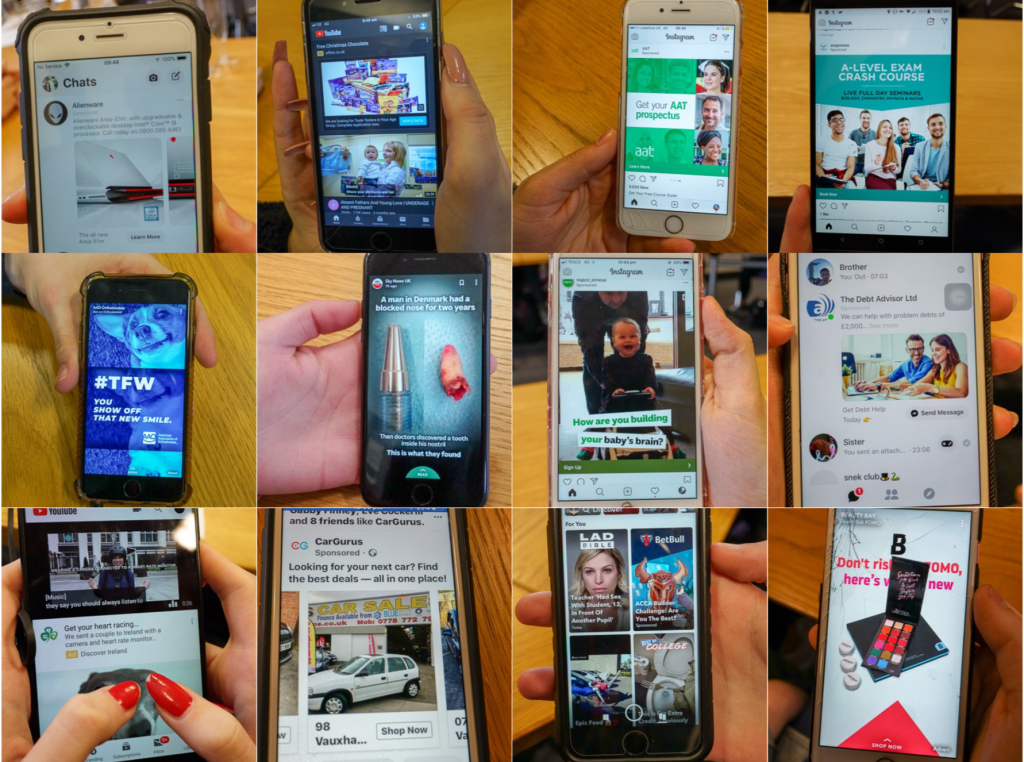

3. Digital Discrimination

This is a project looking at the relationship between location and quality of internet access, the uses that young people make of the internet and the manner in which advertising algorithms feed young people in different areas with different kinds of content. The project is running in Germany and the UK. I have been making images alongside colleagues who are collecting data through surveys, focus groups and mapping. Early days in terms of seeing where this might go visually. Recent interviews in Hull indicate that there might be potential in exploring the ‘layering’ of the located embodied lives of young adults and their virtual lives online (predominantly through their phones).

In relatively poor areas there appears to be a possible interaction between the decaying physical infrastructure (public transport, for instance) and an increasingly complex, and differentiated and disempowering, online world (with snapchat and instagram being used as the dominant means of communication, bringing commercial competition for users’ online attention, but in demographically differentiated ways, driven by algorithms that appear to have a locational component, as well as being shaped by usage).

References

Freeman, L. A., Nienass, B. and Daniell, R. 2016. ‘Memory | Materiality | Sensuality’, Memory Studies, 9(1): 3–12.

Mullen, L. 2019. Mid-century gothic: The uncanny objects of modernity in British literature and culture after the Second World War. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Solway, R. et al. 2017. ‘Material objects and psychological theory : A conceptual literature review’, Arts & Health. Taylor & Francis, 8(1): 82–101.

Stallybrass, P. 1998. ‘Marx’s coat’, in P. Spyer (ed.), Border fetishisms: material objects in unstable spaces. London: Routledge. 187–207.

Juxtaposition of Images and Objects (Week 5 Reflection)

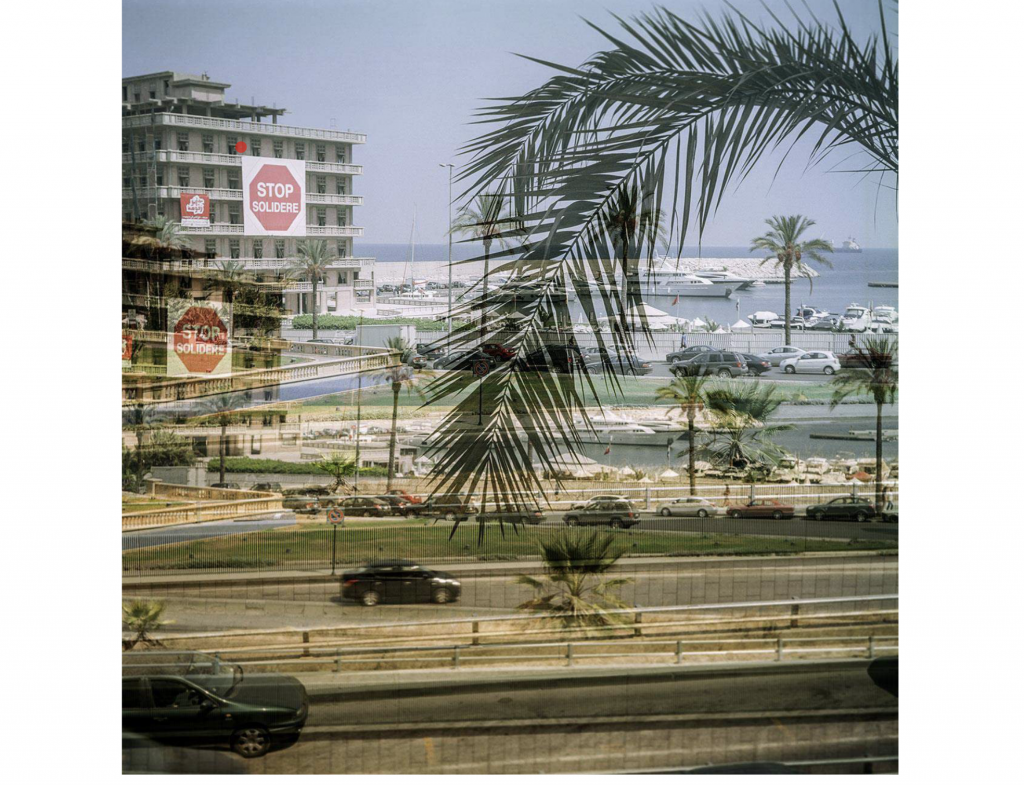

In my presentation for Positions and Practice, I expressed unease about street photography, both in relation to its mode of operation (the prowling, opportunistic, and at times invasive, hunter of images) and the forms of images produced (for instance, those which appear to denigrate or exploit the subject). Consequently, I have moved towards more collaborative forms of image making, but have remained pretty much on the hunter side of the hunter/farmer metaphor invoked earlier in the module. Over the past two weeks, however, in the development of the ‘art’ side of my photographic practice, I have explored constructed images, in particular through a process of multi-channel combining and mixing of images. The intent is to bring together, in a single frame, invocations of the past, present and future of a particular place, and to position human subjects in this hybrid re-imagined space.

The image above combines a photograph of people in a public place, mixed with an image of construction in the area (invoking the future) and a macro photograph of plants found in the mostly heavily developed and concreted space (invoking the past). In my own ‘looking’ I am attempting to identify resources that can be used in the construction of an image that explores the interaction of the past, present and an immanent future, and the relationship within this between the human, natural and built environment. In this way, the visual constitutes material in the production of an image through juxtaposition. Changes in the manner in which channels are mixed can have a marked effect of emphasis within the image, as can been seen in this alternative mix below.

This opens up the possibility of a short moving image that flips continuously from one to the other. It also influences how I shoot and edit, with both the structure and content being influenced by the use of the image in creating the multi-channel work. If I was selecting a single, standalone image from this particular setting, it would, I think, have been the image below, but this wouldn’t work in the creating the mix above (note: forthcoming post on the process and how this relates to intent and theory).

Edmund Clark, in his exhibition ‘In Place of Hate‘, arising from a 3 year study of HMP Grendon (Europe’s only wholly therapeutic prison, specialising in the rehabilitation of violent and sexually violent offenders), included pressed flowers found on the site, as a way of both highlighting the contrast (and resonances) between the harshness of human incarceration and the fragile (but resilient in its insistence to grow in the environment) natural world. My images seek a similar juxtaposition and play between contrasting elements, but within a single image. The process of multichannel mixing (described here), however, both renders each element less distinct, and attempts to convey a sense of the interaction between elements. In this work, I am neither simply hunter nor farmer (though the process entails elements of both), but rather designer, architect, collector, curator, alchemist, experimenter and more. The approach opens up the prospect of both the creation of new images for the purposes of mixing, and the incorporation of archival material, computer generated images and found images.

The resulting images can be considered to be fictions of a sort, pulling together ‘untethered’ materials from elsewhere, and combining different ways of looking (and, therefore, different forms of gaze). The intent of the fiction, however, it to explore relationships in time and space, and thus the approach resonates with the idea of fiction as methods (see my discussion of the work of Francois Laruelle and the arts here). I am producing the work for an audience that wishes to explore ways in which the visual arts can be deployed, in conjunction with other approaches, to explore complex human and environmental issues. How the reader interprets the image depends very much on context, and the motivations and interest of the reader. As with all forms of image making, there is a need also to work to actively create an audience, and to seek appropriate outlets and contexts for the work. The images are clearly challenging to read (given the detail, the prints will need to be large), and the process in the early stages of development.

References

Edmund Clark, 2015-17, In Place of Hate. https://www.edmundclark.com/works/in-place-of-hate/#1 [accessed 04.03.19].