I was fortunate to be able to arrange to meet and talk to two photographers whose work is very different from my own, giving me the opportunity to learn from their experience and think through how I might extend and enhance my practice. In particular, my work to date has mostly focused on places and structures, in which human activity is evident, but without any people in the photographs. My proposed final major project is going to require portraits and other images featuring people, so I want to learn as much as I can from other photographers. The conversations with Hugh and David have also been helpful in understanding the ‘business’ (or, rather, ‘businesses’) of photography, and to give me insight in both the production, distribution and use of photographic images.

Hugh Kinsella Cunningham is a photo-journalist, whose recent work is predominantly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). His photographs of female boxers in the DRC were recently featured in the Guardian.

Hugh Kinsella Cunningham, 2017, Safi Nadege Lukambo, 21, Fight Like a Girl

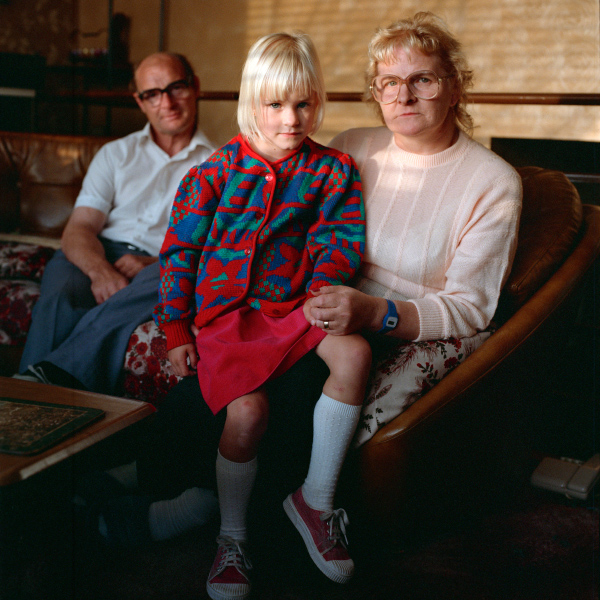

His current work explores political resistance and the catholic church in DRC. These are colour photographs taken in natural light (early morning, never in the middle of the day, avoiding the complications of lighting rigs). As a photo-journalist, there is an emphasis on presentation of a strong narrative through his images. These stories have to be sold to editors, and the viewer has to be drawn into the images. They also have to be true to Hugh’s strong commitment to the people he is photographing and concern for the conditions in which they live. Whilst the settings he is exploring are familiar to me (having worked on education projects in east and southern Africa), the commercial context of photo-journalism is new to me. His advice on producing and presenting images in this highly competitive world was very valuable and challenging. Images have to be sufficiently strong, with a compelling story, to command the attention of viewers, most of whom don’t care particularly about the issues being addressed. Taking time to understand the context and build trust and familiarity is important. Turning up, being around, being seen and engaging. Taking control of the situation is vital, asking people to try different poses, looking at the camera, looking away from the camera, at different angles, in different settings – working the scene. Take 100 shots per session, don’t be embarrassed to shoot, or to organise the setting. In presenting the work he emphasised the need for quality and consistency in look and feel (do a course in photo retouching, if using film use a lab for processing, scanning and printing). Don’t undersell the work (present in a competitive gallery setting). He gave a number of people to follow up, including work by Nicola Muirhead on Trellick Tower in Notting Hill.

Nicola Muirhead, 2017, In Brutal Presence, Trellick Tower, Sue 33 years resident, 18th Floor.

Hugh’s advice: “Just be respectful and confident and it will fall into place”. I’m certainly up for giving it a go, and think I now have some interesting contexts to explore (see following post about this). To learn to make engaging portraits like these is going to be a real stretch. We’ll stay in contact, and Hugh has offered to look at an edit when I have something worthwhile to show, which will be really valuable. I’m not ever going to be a photo-journalist, but engaging with the hard edge to this work will certainly sharpen and help define my own work.

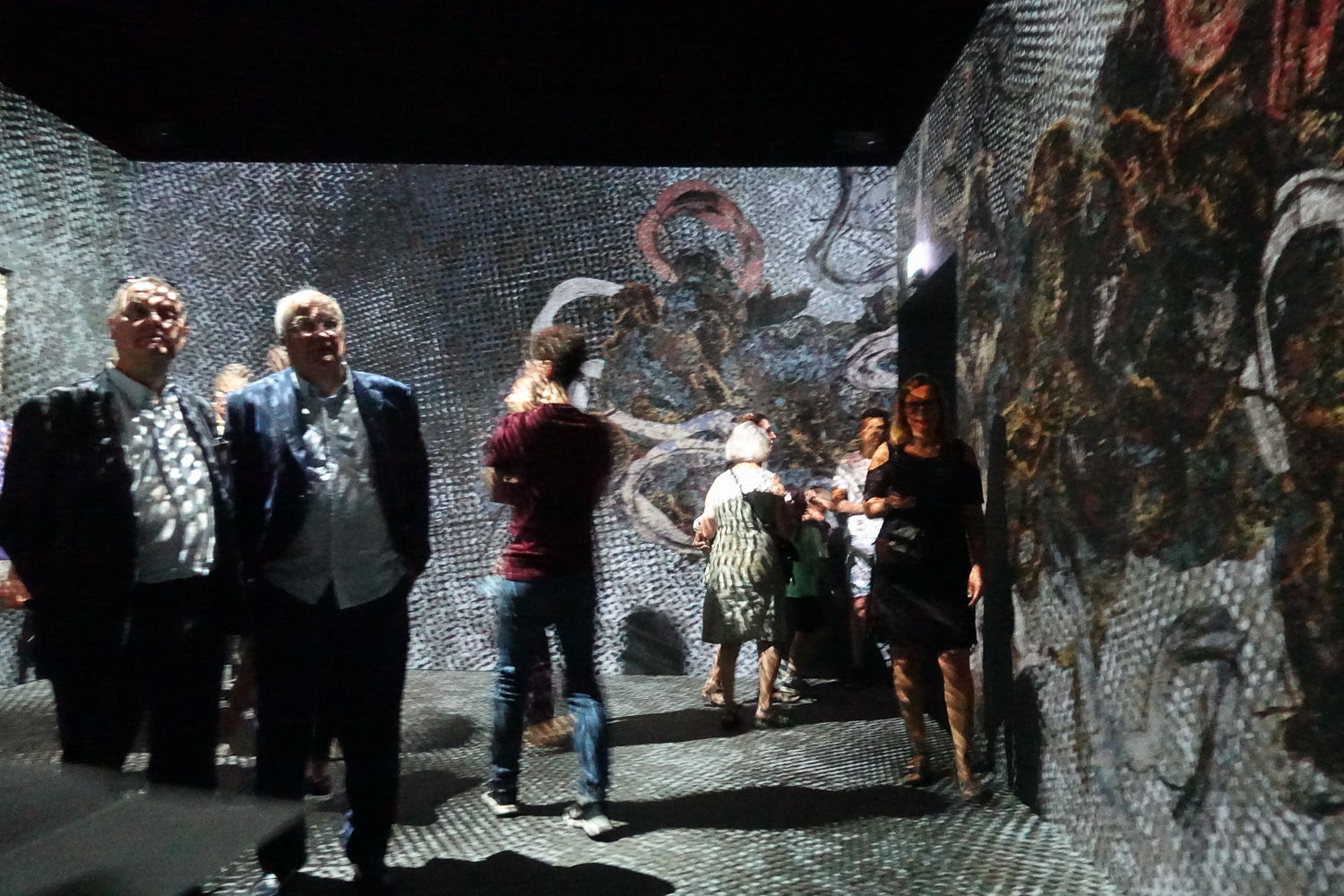

David Wright is a social documentary photographer who trained at the London College of Printing in the 1970s, but whose career took him away from the visual arts and into education. He continued to make photographs and has recently revisited some of his earlier work (for instance, studies of coal mining in South Wales, and photographs taken around Brick Lane in London). His photographs of life in rural west coast Ireland span 30 years.

He is now working almost full-time on his photography, and has initiated a wide-ranging project on ‘Modern Tribes of Britain‘. He works entirely on film and in monochrome, processing and printing all his own work. David describes his approach as anthropological, seeking to get to know and become part of the communities he is photographing. He often meets people and attends events without taking photographs, and builds trust amongst the community members. There is a loose inferred narrative structure in the sequencing of prints, requiring work on the part of the viewer.

David and I intend to meet each month to share and discuss our work. Whilst our images are very different in style, there is much in common in terms of method (for instance, in engaging participants and aspiring to more collaborative image making) and in the contexts that we are exploring. I have a lot to learn from his work, particularly in relation to the development of a distinctive visual style and the craft of image and print making. We have also been able to share contacts and give each other leads in the development of our respective projects, and might develop some collaborative work. One possible area is to work with student photographers who are documenting the work of student volunteers with community groups across London. His work on urban agriculturalists (one of his modern tribes) also cross-over with my work on the impact of urban regeneration on communities.

Jeff Wall, 1982, Mimic

Jeff Wall, 1982, Mimic

An extensive survey, covering both floors of the gallery, of the work of a radical Japanese architect. In a discussion in the previous module, it was stated that how a building will look when photographed was influencing architects in their designs. The absence of photographs in this exhibition is notable.

An extensive survey, covering both floors of the gallery, of the work of a radical Japanese architect. In a discussion in the previous module, it was stated that how a building will look when photographed was influencing architects in their designs. The absence of photographs in this exhibition is notable.