This is the joint statement about the project produced by the group.

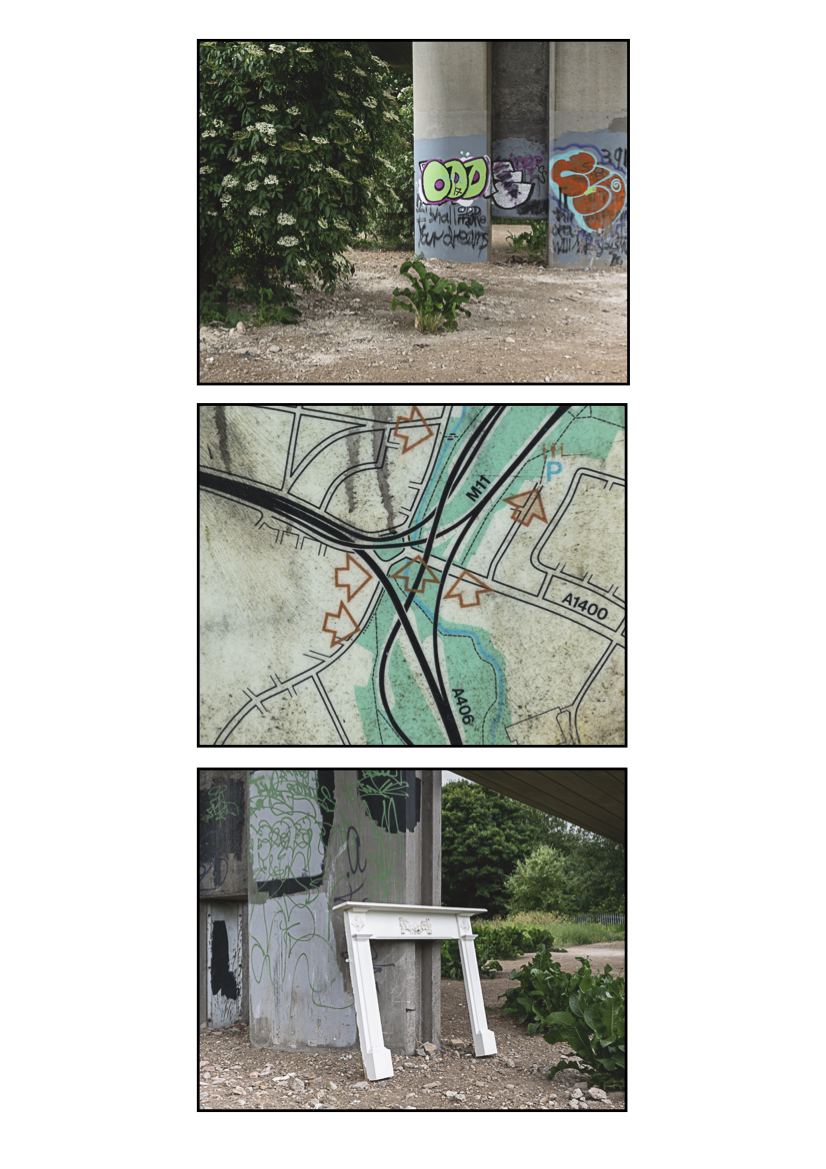

The group took initial inspiration from images by Susan Derges. Our approach was collaborative from the start, attempting to bring together each member’s interests and locations with themes and working practices drawn from Derges’s work. We have attempted to address a number of questions that have engaged Derges, in particular the relationship between self and nature and between the imagined and the ‘real’, and the effect of the observer on the observed. These themes have informed both our process and the final images. We have also adopted aspects of Derges’s method, for instance in the use of experiments (in our case in making images and in exploring water droplets and effects of evaporation). We have chosen to present our final images in the circle format of some of Derges’s recent work. As there is little sense of scale in our composites, we felt that this format conveyed a sense of the ambiguity of both looking in to an inner world and out to an imagined (in our case composite) landscape.

There are, though, a number of ways in which we have departed from Derges’s method, for instance in the use of digital cameras (her work is largely camera-less) and in the creation of composites using photoshop (rather than use of experimental image making methods to produce a single image). Our approach has enabled us to produce a small body of original images in a short period of time through a genuinely collaborative process. We have acknowledged the inspiration of Susan Derges’s images and approach, and our desire, through collaborative image-making, to gain a greater understanding of this work, in the title of the project: ‘Looking for Derges’.

Our method

Our starting point was to take inspiration from images produced by Susan Derges, with particular attention to the relationship between self and nature, and to see if we could take photographs that could be layered to produce images that in some sense resonated with those of Derges. We initially thought we might take images from our respective locations and construct from these, another ‘imaginary’ place. As the group formed, and as we explored Derges’s work (see sources list below) and considered what might be possible in the time available, other points of personal and collective interest came into play. New themes emerged (for instance, loneliness and making images from nature rather than of nature) and approaches to image making inspired by Derges’s work were explored (for instance, experimenting with the evaporation of water droplets and seeing, through macro photography, change take place as water stains formed and pollen fell on the surface). The group members shared images from their experiments and photographic explorations of their local areas and discussed (through the discussion group and face to face video conference) how these could be combined using layering to form composites. Those adept with Photoshop produced composites to consider. We settled on a circle format for the images, as this both acknowledges an aspect of Derges’s recent practice, and is particularly suited to the emerging focus of the project. The images produced are more complex than initially envisaged, which is testament to the value of collaborative work. Our use of digital technology and editing in Photoshop, whilst allowing us to produce some aesthetically pleasing images, may, however, have drawn us away from the camera-less simplicity of many of Derges’s images (for instance, in her Moon and Ash series). There is clearly great scope for further experimentation with this type of work. The final composite images produced are here.

As well as being of great personal and collective value, the process, and the outcomes, are true, in a very modest way, to Derges’s emphasis on process and her aspiration to produce images that are more than ‘illustrating an idea … I’m not telling someone how it is, I’m triggering them to open up to their own experience to either remember or grasp and explore a set of imaginative or reflective processes … It is very much about an exchange or communication’ (Derges quoted in Read & Simmons, 2016, p.124).

Sources

Galleries:

Derges, S. (n.d.). Purdy Hicks Gallery website. http://www.purdyhicks.com/display.php?aID=116#14. Accessed 28 June 2018.

Derges, S. (n.d.). Artist’s website. http://susanderges.co.uk/. Accessed 28 June 2018.

Videos:

Derges, S. (2010). Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography. Video, V&A, 2010. https://vimeo.com/13149808. Accessed 28 June 2018.

Derges, S. (2012). ICP Photographers Lecture Series. Video, International Center of Photography, 14 March 2012. https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/media/icp-photographers-lecture-series-susan-derges. Accessed 28 June 2018.

Interviews:

Derges, S. (2016). ‘Case study’ in M. Read & S. Simmons (2016), Photographers and Research: The role of research in contemporary photographic practice. London: Routledge. 114-125.

Derges, S. (2015). ‘Water, Life and Photography’. Interview with Colin Pantall, 28 September 2015. http://colinpantall.blogspot.com/2015/09/susan-derges-water-life-and-photography.html. Accessed 28 June 2018.

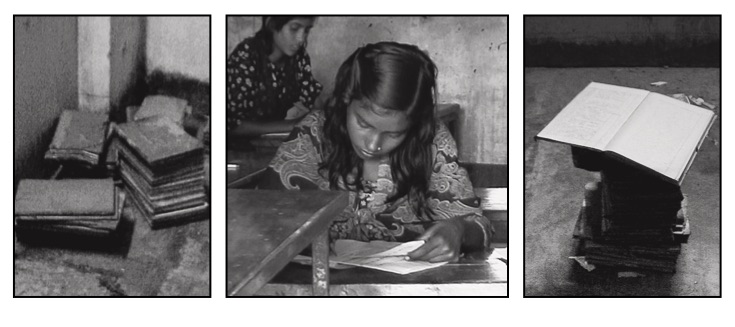

This is the image I have chosen to present (in addition to the ‘re-make’ images) for the Week One online seminar. The photographs were taken in a ‘hard to reach’ school (i.e, one that takes days to get to from the city, and, if it rains, can take much longer to get back from) in 2001 when I was working with the Ministry of Education in Bangladesh. The degraded black and white image makes it difficult to place the photographs in time. The images also have a painterly quality, which challenges the aspiration to mechanical (and now digital) veracity. The activity and objects depicted (books, schoolrooms and literacy practices) also span the history of photography (with mass schooling, based very much around literacy, numeracy and the regulation of behaviour, developing in the UK, through the school boards, from the mid-nineteenth century). Literacy is also particularly important for me; I didn’t learn to read until the age of 8, and when I did, it totally transformed my life, and has shaped my subsequent trajectory. In the case of Bangladesh, and other similar contexts, female schooling and literacy is particularly important. In presenting the images, I wanted to experiment with the triptych format, which invokes an earlier, pre-photographic (and pre-industrial) era in the west.

This is the image I have chosen to present (in addition to the ‘re-make’ images) for the Week One online seminar. The photographs were taken in a ‘hard to reach’ school (i.e, one that takes days to get to from the city, and, if it rains, can take much longer to get back from) in 2001 when I was working with the Ministry of Education in Bangladesh. The degraded black and white image makes it difficult to place the photographs in time. The images also have a painterly quality, which challenges the aspiration to mechanical (and now digital) veracity. The activity and objects depicted (books, schoolrooms and literacy practices) also span the history of photography (with mass schooling, based very much around literacy, numeracy and the regulation of behaviour, developing in the UK, through the school boards, from the mid-nineteenth century). Literacy is also particularly important for me; I didn’t learn to read until the age of 8, and when I did, it totally transformed my life, and has shaped my subsequent trajectory. In the case of Bangladesh, and other similar contexts, female schooling and literacy is particularly important. In presenting the images, I wanted to experiment with the triptych format, which invokes an earlier, pre-photographic (and pre-industrial) era in the west.