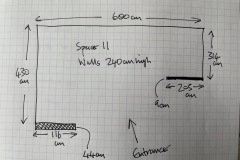

Met with the DFA group on 13th May to look at and allocate the exhibition space. I have Space 11 in AVA G36 (Studio 4) on the ground floor. Starting to think about how I can develop my work over the next few weeks to present something coherent and make best use of the space. Initial thoughts are to take aspects of my current project and explore Mary Douglas’s notion that dirt/pollution is ‘matter out of place’.

Education, Practice and Society Learning Lunch

UCL Institute of Education, 5th May 2021

What can we learn from a student’s experience of designed, contingent and improvised online teaching, and how might this inform our post/perpetual pandemic practice?

I was fortunate to be a guest at the EPS Learning Lunch to share my experiences as a learner over the past three years, assembling formal and informal learning experiences in photography and fine art. Reflection on the pedagogic structure, relationship between and student experience of the components, which taken together correspond to progression from undergraduate to postgraduate taught to postgraduate research levels (see links below), spanning the contingencies of pandemic management measures, provided an opportunity to think again about the relationship between different forms of educational provision and learner trajectories. This raises issues of learner agency and responsibility, the strategies and tactics used by learners and the meaningful assemblage of educational experience at a time in which knowledge is increasing seen as a commodity and education framed in terms of providers and consumers. Some resonance here with Stephen Wright’s (2014) exploration of the ‘useological turn’ in the arts, and a shift from spectatorship to usership. Discussion invoked the issues and approaches explored by the Vauxhall Manor School Talk Workshop Group (1974-79).

Outline

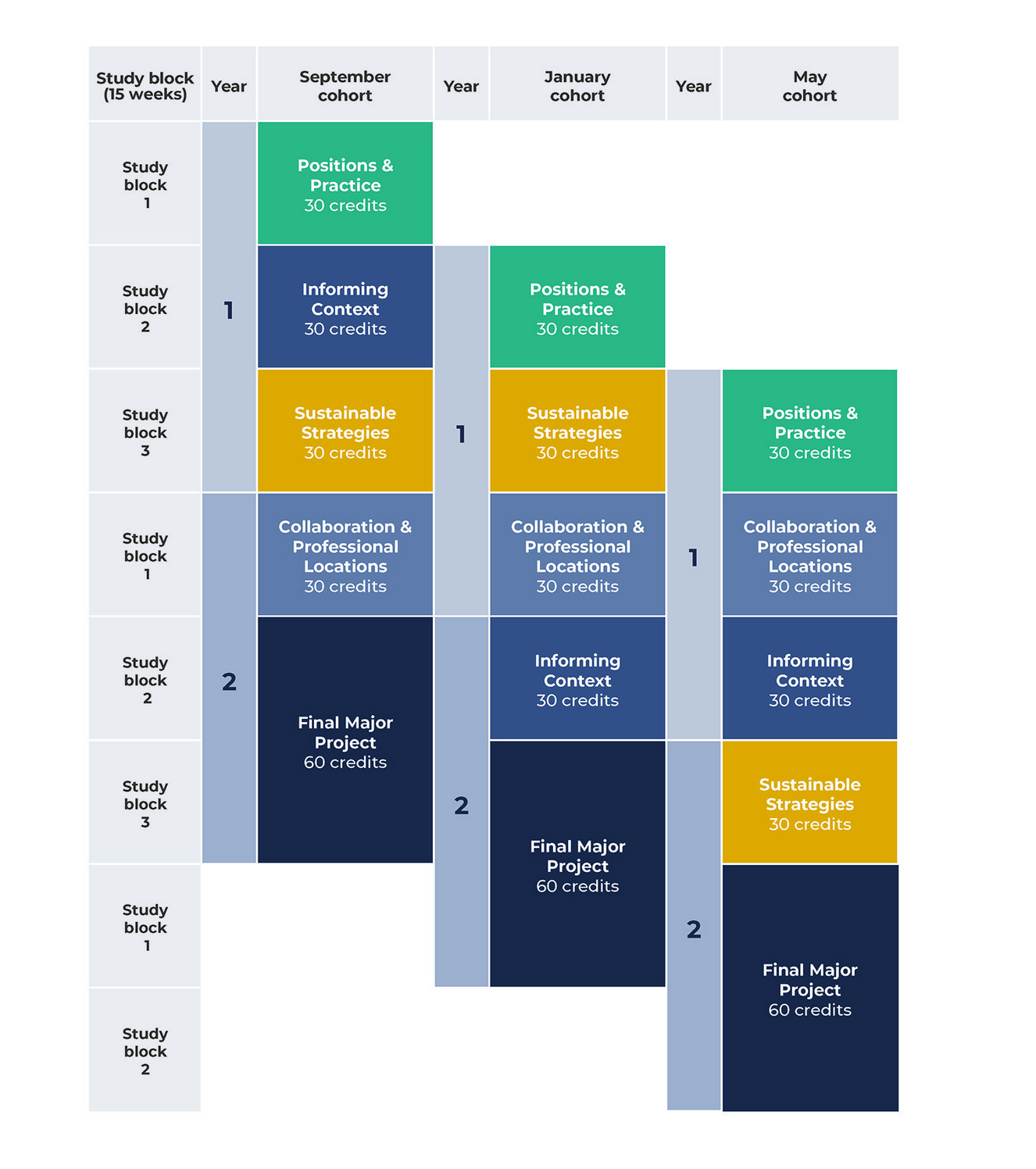

Three years ago, I left the Institute, rewound thirty years to a fork in the road and took the other path. Since then I’ve combined posts in London, New South Wales and Singapore with education and practice as a photographer and artist. This has included the combination of online and face to face non-accredited courses and awards, an online MA at Falmouth University and a Professional Doctorate in Fine Art at UEL, my local university. At this learning lunch I want to reflect on what I have learnt, as an educator, from the experience of being a student in a range of contexts, and consider the manner in which universities have responded to pandemic related restrictions.

Through an initial 20 minute presentation and subsequent discussion I will consider the pedagogic structure of each of these forms of educational experiences from a student’s perspective and hope to draw on the experience of participants to consider at least some of a the following questions:

- where does responsibility for learning lie, and how do we align expectations?

- who is accountable for learning and how?

- what is the relationship between informal student-led support networks and formal provision?

- if the formal taught component of a programme is the visible tip of the learning iceberg, what lies beneath the surface?

- to what extent can student groups be considered a community?

- how can higher education programmes appropriately recognise and accommodate the skills, knowledge and experience of learners?

- what is the role of ‘usership’, bricolage and improvisation in the development of an educational programme and a learning trajectory?

- what can we learn from student experiences of specifically designed online programmes for the contingent development of online provision?

- what can we learn from student experiences of the contingent development of online provision for the design of online programmes?

- is higher learning in the throes of deinstitutionalisation?

- am I as atypical a student as I might at first seem?

OU/RPS Online Certificate in Digital Photography

City Lit workshops

Open Studio Workshops

RPS Licentiate workshops

RPS Licentiate assessment

MA in Photography

Four Modules

Final Major Project

Guest lectures

Repository

Workshops

Meetups

Lewis Bush Workshops

The Photographers Gallery Workshops

London Centre for Book Arts

Rapid Eye Darkroom

Arte Útil

Professional Doctorate in Fine Art

London Alternative Photography Collective

Institute of Making

Art21

Self-Publish Be Happy

A working learning day

Thursday 6th May 2021

Reflecting on issues discussed at the Learning Lunch, I thought it might be useful to map out how working/learning plays out by tracking activity over the following day. The working bit comprised of answering and following up on work-related emails (jobs in UK, Holland, Singapore, Australia), online meetings about governance issues at an FE college, preparation for upcoming meetings, reading a book manuscript and producing test prints for a forthcoming exhibition. Not sure whether updating supervision notes on the UEL PhD Manager system counts as work or learning, but I did that, too.

The distinct learning events were as follows (before work, at lunchtime and after work in this case, but they could as easily have been woven into the working day).

8.45-9.30: Curator-led online tour of the Sunil Gupta retrospective and Evgenia Arbugaeva exhibition at The Photographers Gallery. Pandemic measures have meant that the exhibitions were hung but not open to the public. The exhibition schedule entails that they will now, all being well, only be open to the public for two weeks. The online participants were patrons of The Photographers Gallery, so this was essentially an online substitute for a curator-led private view. I’m familiar with the work of both artists, so the interest here was principally in how the work is presented in the gallery setting and the process by which curators and artists work together. As Gupta’s exhibition is a retrospective, there are decisions to be made about which bodies of work to include, how to distinguish between them and how to relate them to each other. The sequencing of the work, the flow through the gallery and the tight correspondence of the work to phases in Gupta’s life give the exhibition coherence, despite the marked differences in the form taken by each successive project (and the idea of a project frequently being developed post-hoc).

In contrast, Arbugaeva’s exhibition presents a single project, and thus places an emphasis upon creating an environment/atmosphere which enhances the viewers’ engagement with the work. Apart from a graphic map of the area in which the images were made and a short introductory text, the work is visual, and brought together as a coherent whole though gallery layout, colour, lighting and other aspects of design, invoking the dark Russian arctic winter.

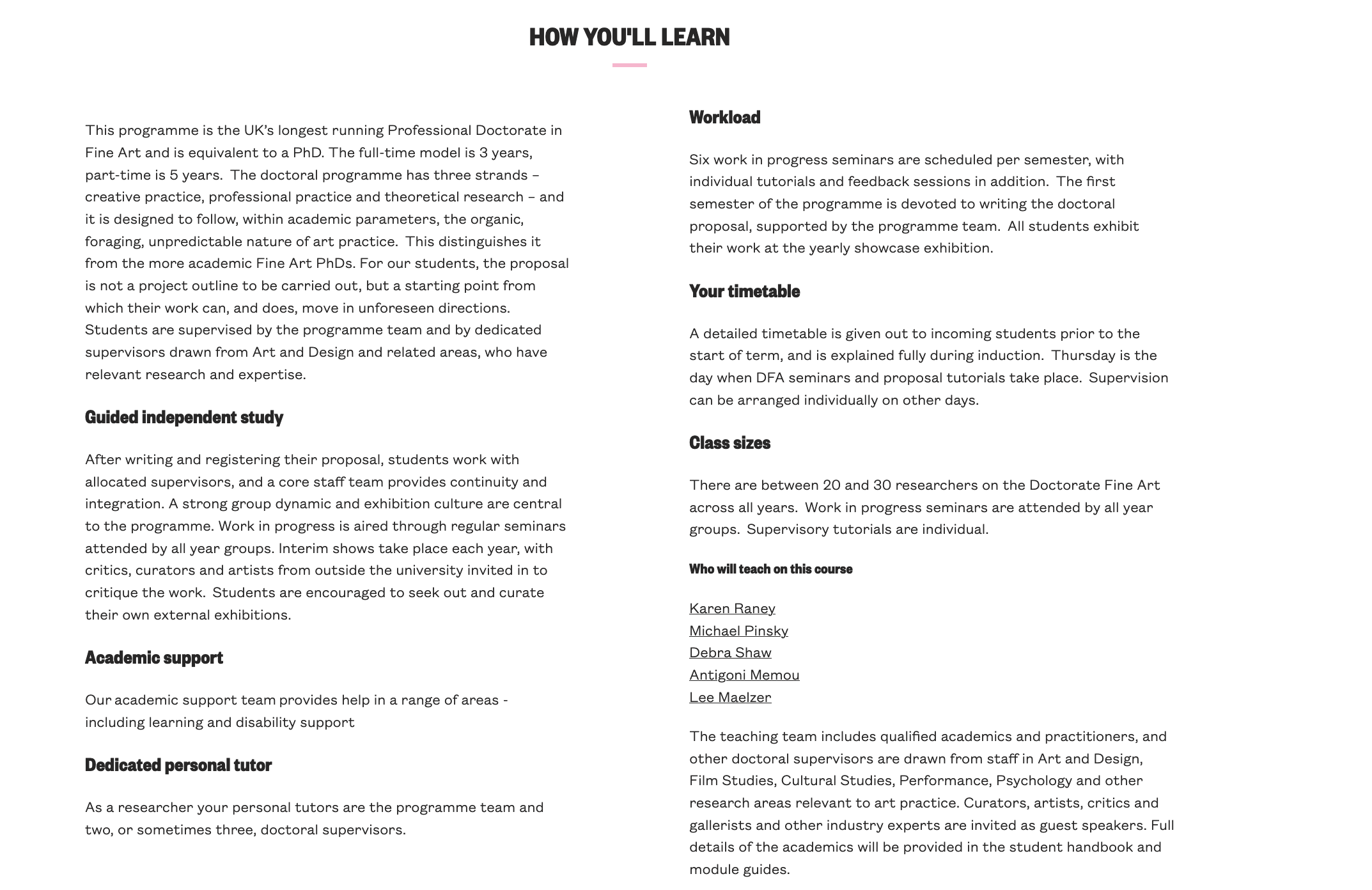

13.00-13.30: Online presentation by photographic artist Rut Blees Luxemburg about public engagement in art using her own work as examples of different modes of engagement. This was part of a programme of activities for undergraduate architecture, art and design students at UEL, and the audience was a mixture of students in a workshop on campus and people who had logged in from outside.

This is work that I know very well, so the interest here is in the particular modes of public engagement, from the printing of images on large concrete panels for the Silver Forest project in Westminster to holding events and seminars (involving, among others, Jean-Luc Nancy) to launch the London Dust exhibition at the Museum of London. Particularly interesting was the opening of Luxemburg’s own artspace Filet in Shoreditch, which she uses as a way of engaging the public with the work of young and emerging artists. The message here is make sure that these community events and opportunities for active engagement are built in to the project, to create dialogue and discourse around the work.

I’d intended to go to the session by film maker Alison Winter but my preceding online meeting over-ran.

17.00-18.00: Points Run: A One Act Play, Written and Performed by Sheridan Humphreys. This was a public online event run by the Menzies Australia Institute at KCL, where Humphreys holds a postgraduate research scholarship. The participants were mostly in the UK and Australia. Humphreys, who is both a PhD student and a lecturer in Screenwriting at Greenwich and Royal Holloway, explored the use of fiction and performance as modes of investigation and representation in research.

The initial performance acted to provoke discussion both about the substantive focus of the piece (domestic violence and domination) and the use of fiction and speculative forms as a means of investigation/research in the humanities. This resonated strongly with O’Sullivan’s (2017) exploration of fiction as method, developed from an engagement with the non-philosophy of Francois Laruelle (2013). The influence of Sara Ahmed‘s work on Humphreys’ approach also resonates with the work I’m doing with the Centre of Excellence for Equity in Higher Education, and Ahmed’s (2019) exploration of ‘use’, particularly in relation to educational institutions and practices, has direct relevance to the bringing together of my own background as an educator and the development of my current artistic practice.

18.30-19.15: Listened to the Free Thinking episode on Epistemic Injustice while in the bath. Miranda Fricker’s (2007) notions of testimonial and hermeneutical injustice bring us back around to the discussion of student voice and agency in education institutional settings at the Learning Lunch (as does Ahmed’s forthcoming Complaint!), and Basil Bernstein’s question of whose knowledge is valued and transmitted through formal education and, in relation to assessment ‘whose ruler, in whose interests or for what consciousness, desire and identity?’ (in conversation with Joseph Solomon, 1999).

Actually not an atypical day in terms of the range of engagements and diversity of activities. Taking time to make the links between these experiences is a challenge. Writing this has taken longer than it should. It occurs to me that it would not be possible to ‘attend’ such a range of presentations in a day of face to face activity, raising again the question about what we can learn about modes of higher learning from our pandemic pedagogic improvisation, and the need to stop seeing this a pathological episode to be set aside in the return to ‘normality’. There is also a lot here, prompted by relating this art/photographic life/education to my experience as an educator and sociologist, that contributes to an understanding of plurality in practice and in producing a productive dialogue between domains of practice. Brewing alongside this is consideration of Tim Ingold’s (2021) Correspondences and John Newling’s (2020) Dear Nature, which start to draw together other loose but approximal ends, but that’s for another post.

References

Ahmed, S. (forthcoming). Complaint! Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ahmed, S. (2019). What’s the Use? On the uses of use. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Bernstein, B. & Solomon, J. (1999). “Pedagogy, identity and the construction of a theory of symbolic control”: Basil Bernstein questioned by Joseph Solomon. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 20(2), 265–279.

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ingold, T. (2021). Correspondences. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Laruelle, F. (2013). Principles of Non-Philosophy, trans. Nicola Rubczak and Anthony Paul Smith. London: Bloomsbury.

Newling, J. (2020). Dear Nature,. Nottingham: Beam Editions.

O’Sullivan, S. (2017). ‘Non-philosophy and art practice (or fiction as method)’. In J.K. Shaw and T. Reeves-Evison (eds) Fiction as Method. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Current and future practice presentation

Presentation given at the DFA workshop on 18th March 2021.

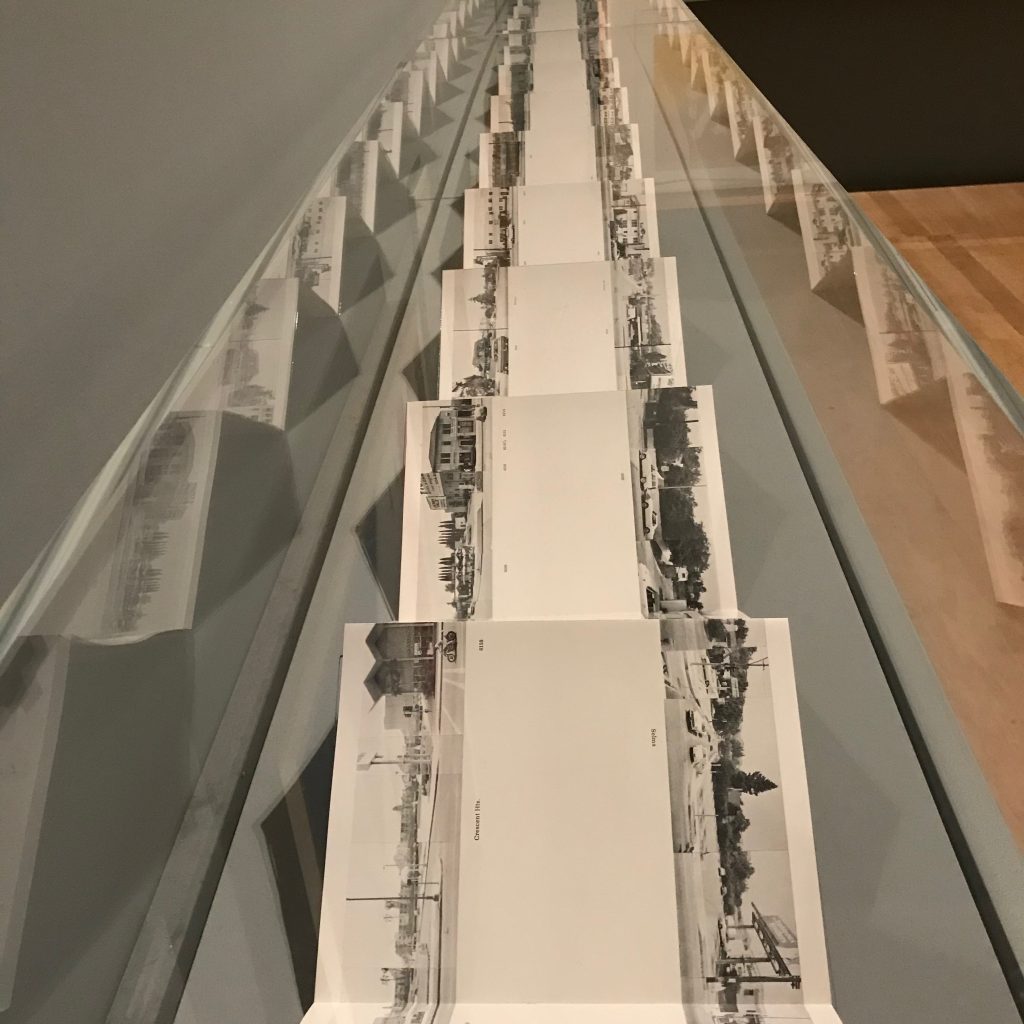

AB-current-and-future-practice-final-compressedDeutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2020

The Photographers’ Gallery, 18th August 2020

No Arles this year, but fortunately I could get to the Deutsche Börse shortlist exhibitions at TPG (see reflection on Arles 2019 here and last year’s Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize here). Half a gallery is given to each of the four nominees, over two floors. The material presented has to represent the work for which each artist has been nominated, and this varies in both form and content (in one case this is a book, represented by prints and a small text produced for wider distribution including gallery visitors, in another case a large exhibition above a supermarket, represented by a small selection of works in a constrained gallery space). The visitor thus gets only a limited sense of the work in each case.

The exhibition provided the opportunity to reflect on the relationship between artistic practice, a specific project and set of outcomes (including the kind of exhibition that might warrant nomination for this kind of award). The work presented by the four nominees here mark out different positions.

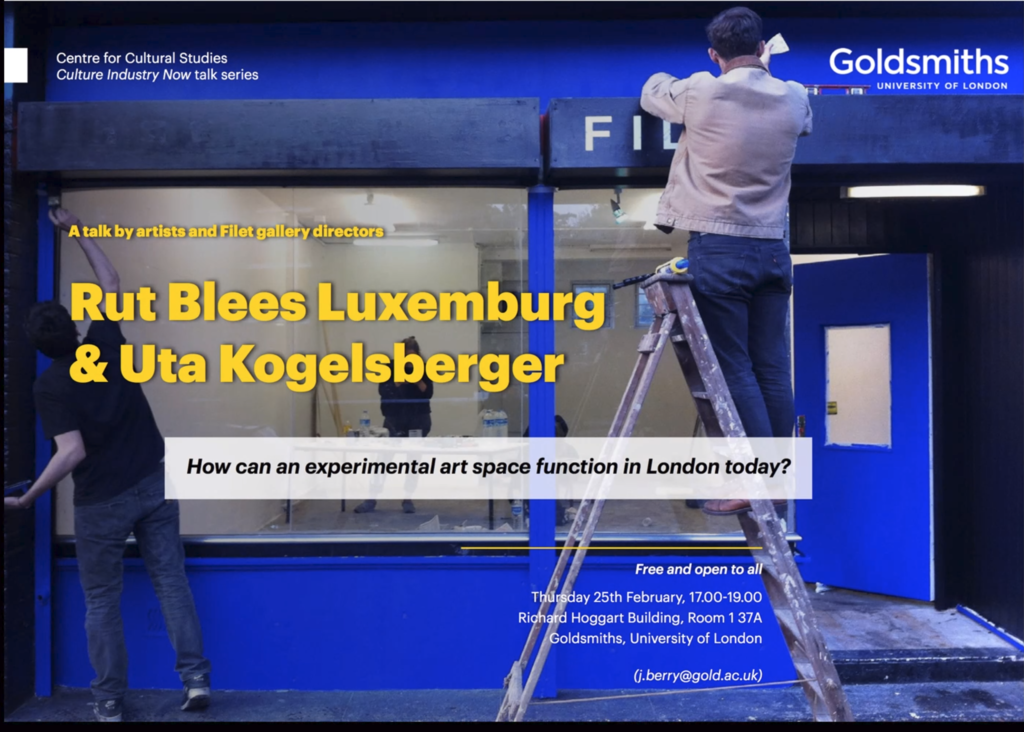

Anton Kusters is nominated for The Blue Skies Project, exhibited at Fitzrovia Chapel, London (15-19 May 2019). It comprises of 1078 upward polaroid photographs of the sky from the last known locations of Nazi concentration camps taken over a period of 6 years (using a Holga plastic camera with a polaroid back). Each is stamped with the number of victims and the GPS location. There is an accompanying generative sound piece by Ruben Samara which unfolds over a period of 13 years – the time that the camps were operational. It’s a highly atmospheric and engaging piece, even in reduced form. For me, it’s interesting in the combination of sound and visual material to create a setting. The lo-tech image-making also resonates with the overall approach, which departs from conventional photographic documentation. There is a combination of the systematic (in the research process, the grid layout, the stamping of the images with time and mortality data) and the lyrical. From this an immersive and reflective setting is created. The project itself has a tight focus that relates to a tragic period of European history. The individual images have limited meaning/intrinsic value, but together make a powerful statement and provide the basis of an immersive material experience. Time and duration are important both in terms of the production and experience of the resulting work (the exhibition), and the enduring memory of the horrific events invoked by the work.

https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/dbpfp20-nominee/anton-kusters

Clare Strand’s The Discrete Channel with Noise exhibited at PHotoESPAÑA (5–21 June 2019) is an even more tightly contained (or framed) work, involving the exploration of a 1930s theory of communication in visual terms. A method, consistent with the conceptual origins of the work, is designed and enacted. The exhibition presents the final work (large prints of the the paintings produced) and elements of the process (original photographs with grids superimposed, and the brushes used in making the paintings). The form taken by the project and exhibition raise broader issues about the process of digitisation, transmission and reception.

https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/content/db2020-clare-strand

Mohamed Bourouissa is nominated for an exhibition surveying the past 15 years of his work at Arles last year, Free Trade, which took up the entire first floor of a supermarket. Bourouissa works in a variety of media (including sculpture, 3D printing, painting and video), though this is not as evident in this selection from the Arles exhibition. His photographic work includes found images, stills from surveillance cameras and collaborative image making with participants. The selected work gives a sense of the range of issues addressed by Bourouissa (for instance, the tensions between commerce and markets and marginal social and cultural groups) and his mode of working. Whilst Kusters and Strand are nominated for clearly defined ‘projects’ leading to a distinct outcome (an exhibition, in Kuster’s case designed for a specific setting), Bourouissa’s nominated for an exhibition surveying a range of projects and representing his work over an extended period – it is about him as an artist, and his distinct set of concerns and way of working, not a particular project.

https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/content/db2020-mohamed-bourouissa

Mark Neville is nominated for a photobook, Parade (Centre d’Art GwinZegal, Guingamp, 2019), based on project focussing on a particular place (a rural community in Brittany) at a particular time (three years starting from the 2016 UK Brexit referendum). It is a community based project involving constructed and documentary photography and video to produce a portrait of a farming community, including its relationship with agribusiness. The outcome of the project is a book produced with and for the local community (rather than for an art community), and a contribution to a political campaign. This takes the form of a book in French and English containing a call to action and interviews with local famers, which has been distributed to politicians, and reproduced for visitors to the exhibition. As with Kusters and Strand, this is a tightly focused project with a clear rationale and well-defined outcomes. Neville has a particular way of working, and the production of books for a community are integral to his work. For each project, he needs to find contexts for which this way of working will be productive, and produce distinct outcomes.

https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/content/db2020-mark-neville

Apart from learning from the work of each of the four photographers (which is clearly fruitful and important, particularly in the combination of different media and modes of engagement and participation), it’s interesting to think about the relationship between an artist’s approach/practice and what constitutes a productive project and appropriate outcome. This also has to be thought through in relation to the ‘market’ (broadly conceived) for art (including awards and prizes). Each has a distinct way of working, and a repertoire of techniques, both relating to how images are made, and how participants and audiences are engaged. The three projects (Kusters, Strand and Neville) each have clear thread running through them the give the overall project both value and interest in a co-ordinated and coherent manner. This is more than just clarity of ‘intent’, but rather clarity of design (the same might be said of Bourouissa’s projects that feed into his retrospective exhibition) and coherence of method and conceptual base. Internal coherence is necessary but not sufficient: the project also has to be seen to have wider relevance to the field and/or wider social and cultural practice. The four bodies of work also raise a question about the possible form and scope of work that could be considered for prizes such as this, what is excluded and the impact this has on what kind of work receives wider recognition.

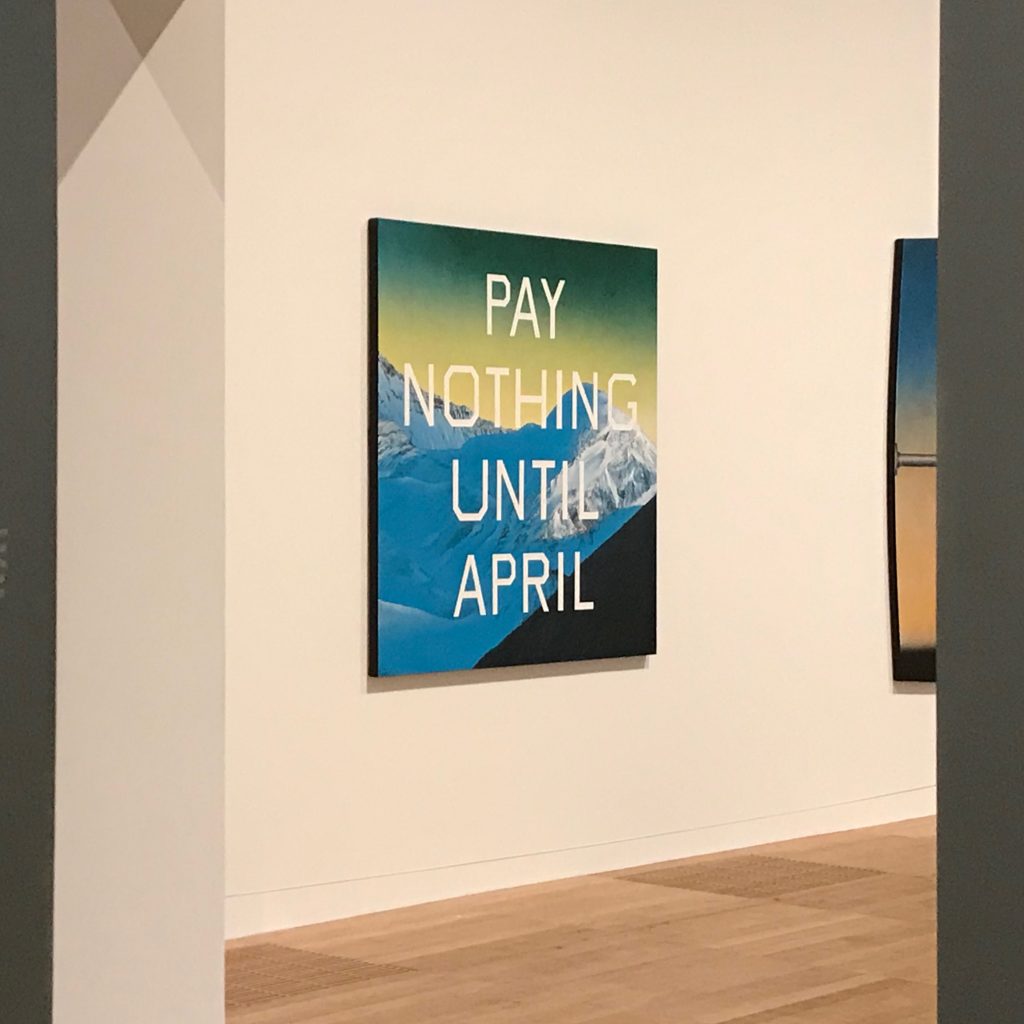

Commercial values

Over the next few months I want to consider different commercial models (and in particular, how these might relate to community art, and alternative ways of funding this type of work). Warhol plays a key part in defining the limits in the production of marketable original art, building on Duchamp’s questioning of the need for the artist to be the ‘maker’. The separation of the artist from the market (value) is neatly explored in Nathaniel Kahn’s 2018 film The Price of Everything. Collector Stefan Edlis reflects on the absence of work by Jeff Koons (a key contemporary exponent of the ‘factory’ mode of art production) in the 2016 auctions, noting that “the real estate people started thinking of Jeff Koons as lobby art”, to which Sotheby’s executive vice president Amy Cappellazzo adds “The kiss of death. You never get out of the lobby once you’re in there.” The trajectory of Larry Poon’s is presented as a counter example, having drifted into obscurity by turning away from the initial commercial success of his 1960s ‘op-art’ dot paintings to pursue his own artistic interests, to be ‘rediscovered’ by the galleries in later life. Poons ceases to produce the dot paintings before market desire is fully developed (so achieves rarity but before securing sufficient market prominence).

This resonates with the painful trajectory of Richard Hambleton, as portrayed in Oren Jacoby’s 2017 film Shadowman, who came to prominence as a street artist, around the same time as Basquiat and Haring (though he appears to have been significantly more conceptually sophisticated, and diverse in terms of artistic practice, than his renowned street art contemporaries). Hambleton’s use of drugs and chaotic lifestyle, and latterly skin cancer, appear to have thwarted a more conventional ‘art-life’, exacerbated by a change in direction (from street art to landscapes) at the point at which his work was reaching a critical stage in terms of recognition, mirroring Poons. Like Poons, he has also continuously produced work motivated by his own artistic interests and drives (frequently against the grain of the prevailing market), and was subject to a number of ‘re-discoveries’ by collectors (with the attendant exploitation, often, in Hambleton’s case, in the form of accommodation, food and/or a studio in exchange for new works, and entailing in some cases intimidation from so called ‘benefactors’). The prolific, and extended, production of new work, of course, undermines rarity and thus effects market value. Basquiat’s biographer, Phoebe Hoban, states ‘both Basquiat and Haring, without meaning to sound as cynical as this sounds, they made a very good career move; they died’. Chillingly, Hambleton, reflecting on the rise and demise of Basquiat and Haring, presents his own trajectory as a form of living death (“At least Basquiat, you know, died. I was alive when I died, you know. That’s the problem.”).

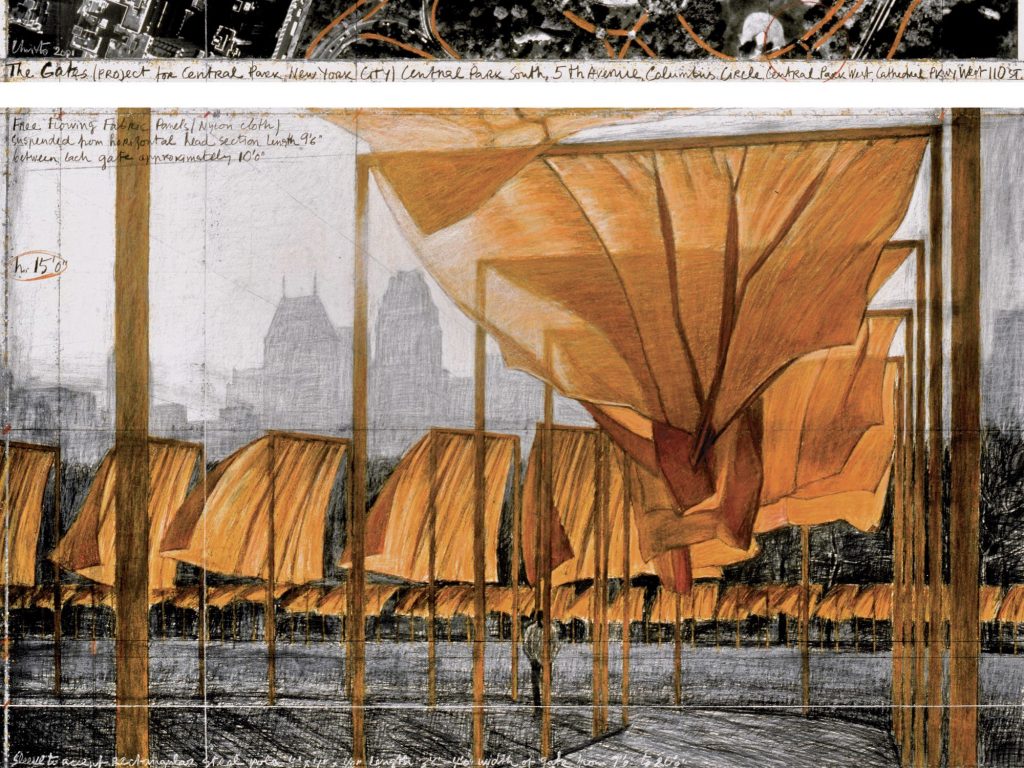

Christo and Jean Claude exemplified an alternative approach. No public funding was received for any of their large scale public art works, for which the legal costs alone amounted to tens of millions of dollars in some cases. Funding was raised through the sale of Christo’s preliminary drawings and other visual work relating to the development of the pieces. The rarity of the work is ensured by the limited volume and time frame in the preliminary, planning and realization stages of the work. The desirability, for collectors, is enhanced by the impact and public profile of the public works. Whilst this is only a viable strategy for artists of substantial standing, producing my own work alongside participants and selling this would be one way of funding community-focused art projects (taking care to put all proceeds back in the community, and to be fully transparent in this use of income from this work). Though not a dominant issue for me, I’ll come back to funding and commercial issues when I post about the 15th August online workshop with Lewis Bush, and to consider again the idea of hidden labour in artistic production.

[Whilst putting together a piece for the DFA programme, I have come across other posts from the MA that address this issue, for instance this reflection from the first module. This raises the question of how best to draw on this material in working towards the doctorate, and whether some work needs to be done to draw out key themes and provide links to where they are discussed].

Warhol and McQueen at the Tate Modern

Tate Modern, London, 14th August 2020, Andy Warhol and Steve McQueen

My second visit to the Tate post-lockdown. Relatively few people around. The timed entry to the exhibitions appeared to work well, restricting the number of people and allowing plenty of time to engage with the work (particularly important for the longer film pieces by McQueen, which have a specific start time).

The Warhol exhibition presents a wide range of pieces by Warhol alongside photographs, texts and artefacts (Warhol’s wigs, for instance) that document and reflect on the activities surrounding the production of Warhol’s work (for instance, ‘The Factory’) and the development of Warhol as an artist (and, indeed, a work of art in himself). Photography is at the heart of all this work, from the photographic foundations of the iconic screen prints through to documentation of events at The Factory (like Stephen Shore’s 1965-7 monochrome photographs) and portraits of Warhol and collaborators.

Much of the screen printed work starts with informal polaroids, and combines printing and painting (so gets me thinking again about mixed media work). The scale of the work indicates the aspiration to sell to a particular market from the start (a market that can both afford and house large pieces).

With the multiples, the flaws introduced by repeated printing, and varying colour schemes, ensures that, despite the quasi-industrial production process, each piece is unique (maintaining provenance and rarity). The paradox here is that the original polaroid is itself one of a kind. Rendering the image as a silk screen print makes it infinitely (with care) reproducible, but painting on the print, and other treatments, return each incarnation to an individual work.

The value of other photographic images in the exhibition is underwritten by their ability to bear witness to, elucidate and contextualise the myth of the artist and their work.

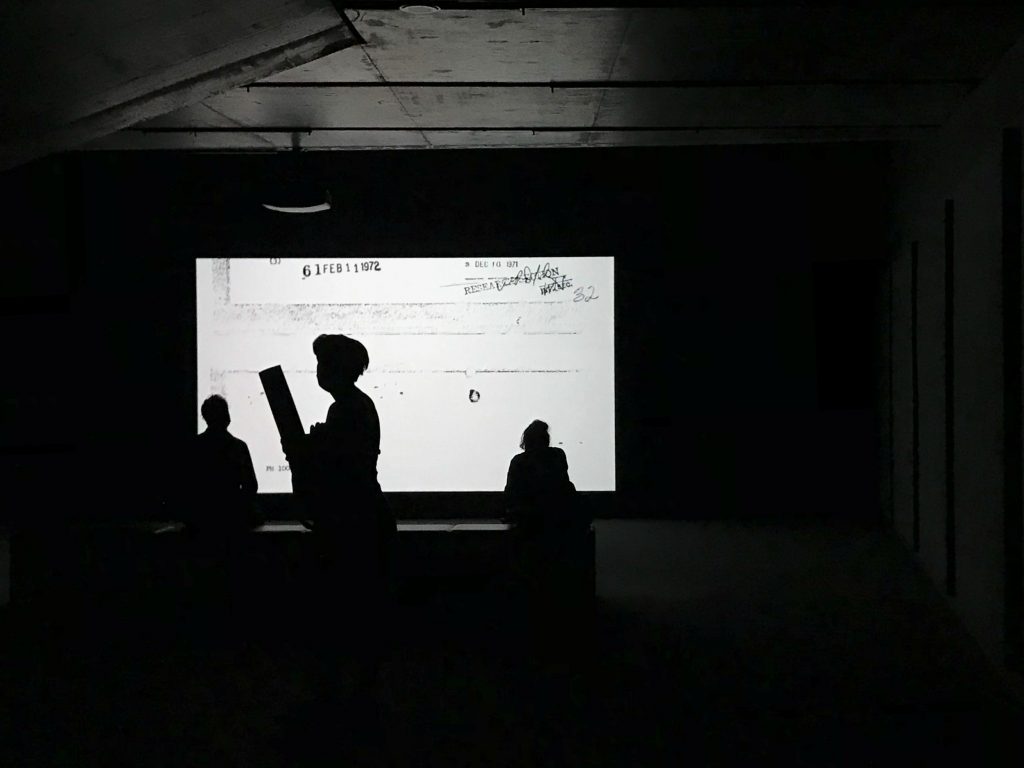

There were some powerful film pieces in the McQueen exhibition, in particular Western Deep (2002), filmed in the TauTona gold mines in the Witwatersrand Reef near Johannesburg in South Africa. The projection pieces were interesting, especially the film pieces in which the projector was a part of the exhibit.

Overall, however, the gallery didn’t seem like the right context for seeing the pieces as a collection.

Tate Modern: How Art Became Active

My first excursion to a ‘public’ event since lockdown. Booked online for a timed entry (first of the day). Arrived at 9.30 for 10.00 opening and was the only person there (orderly queues started to form shortly afterwards). Most people must have been there for the Warhol or general collection, as I didn’t see one other member of the public in 90 minutes in the galleries I visited (a women with a pushchair walked through the last gallery visited).

It was great to spend time (alone) in the Ruscha artist room, with lots of familiar work (a whole room of the photography books, for instance; brought back memories of actually being able to handle these at the Art Gallery of New South Wales print room).

Bringing the work into one place reinforces the diversity of form and the singularity of interests in Rushca’s work. One piece that I hadn’t seen before, but particularly liked, was The Final End.

This juxtaposes a filmic Hollywood closing title with the grassy Californian landscape. Whether the film industry marks the end of rural California or the landscape reincorporates and outlasts human activity is left open (the gothic script, invoking early Hollywood, and the celluloid like markings on the canvas, suggest the former).

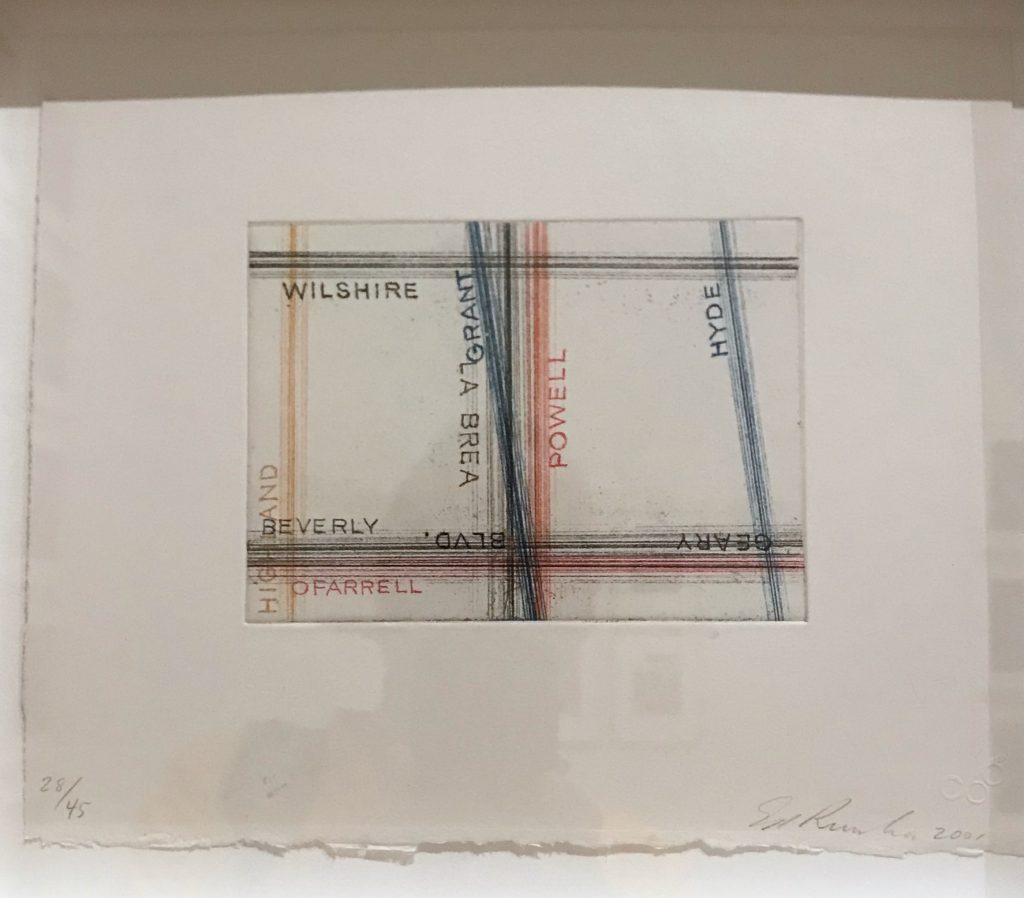

The sketches overlaying major roads in San Francisco and Los Angeles were also interesting, in creating a conceptual link between two particular places at a moment in time. The roads are abstracted from context and overlaid in a new imagined place

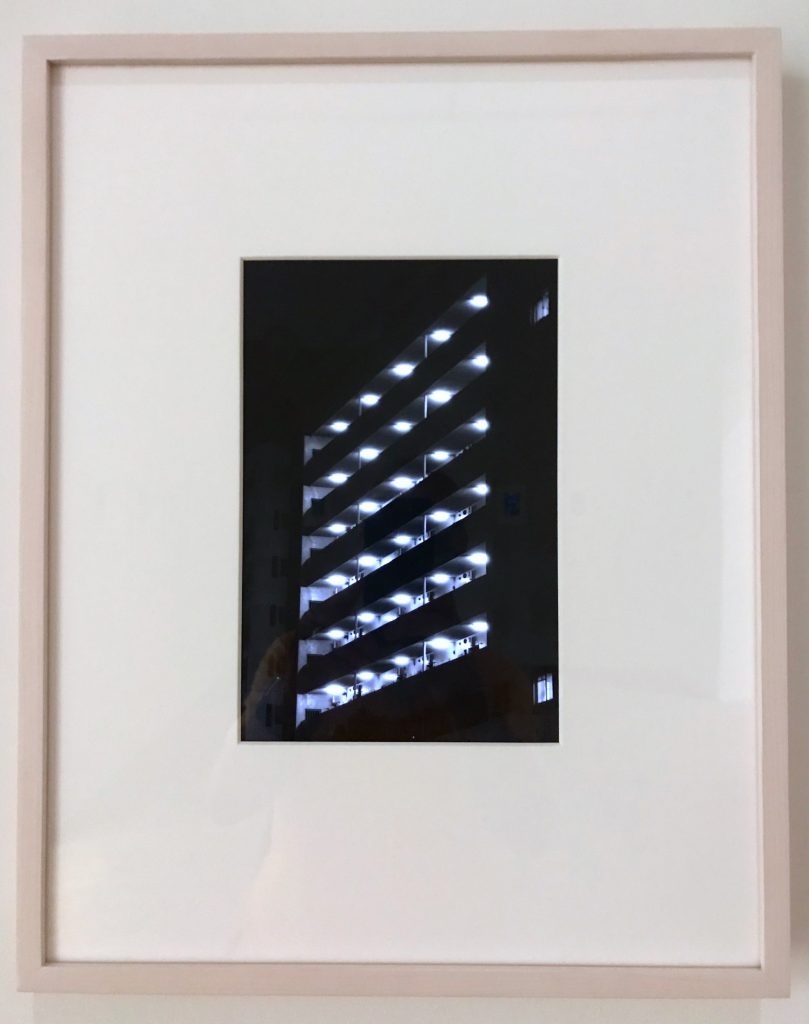

The real delight, though, was unexpectedly being able to see Hatakeyama’s (1995) ‘Maquettes/Light’ series. These are formed from black and white photographs taken at night, with a print on paper and as a transparency overlaid on a light box, increasing the contrast between the blackened structure of the buildings and the brightness of the lights that (fail to) illuminate them.

There is an interesting question to address here about scale. These are small pieces that require close inspection, contrasting with Hiro’s (1962) Shinjuku Station , an almost life size image of a crowded metro carriage taking up an entire wall of the neighbouring gallery, and six of Birdhead’s large one off analogue monochrome snapshot-like prints, Welcome to Birdhead World Again, 2011.

First DFA post

There’s no requirement or expectation to keep a public journal for the UEL DFA programme, but, as I found it both a useful discipline and a handy repository for ideas on the Falmouth MA programme, I’m going to resume periodic posting. The principal outcome of the first year of the programme is the development of a research proposal, so I will document that here. The programme is, however, practice-based, so the journal will also follow the development of my work more broadly. One of my objectives for the programme is to bring closer together my recent photographic/artistic work and my earlier academic/professional work. A sense of where I’m coming from and where I might be heading is given in my application statement. The programme starts on 27th September.

DFA application statement

My work explores the entanglement of the human and the non-human at a specific moment in time and in a particular place, invoking imagined and enacted pasts and futures. I move between analogue and digital forms of image-making, manipulation and distribution, and juxtapose images with text, documents, maps, accounts, soundscapes and artefacts. In producing the work, I create contexts within which I can work alongside other participants in a manner that is ethical, sustainable, respectful and of mutual benefit. What we learn from each other enhances what is produced and vice versa. I am particularly committed to inter-disciplinary and inter-professional work, and the exploration of what the arts can bring distinctively to enhancing understanding and supporting effective social action.

My involvement with photography stems back to working as a child model at the age of four (payment, four guineas a session). From that staring point, hanging around in studios, playing with cameras and lights and dabbling in the darkroom, I have produced my own photographic images, with both analogue and digital capture, processing and presentation, and have entwined this with my professional work as teacher and academic, for instance, working with the Blackfriars Photography Workshop to involve primary school children in photographic image making, running photography workshops for trainee teachers and using photography in social research (including two co-authored social research books with sections on the use and analysis of images).

The nature of my work can be illustrated by my MA final major project (FMP), completed earlier in 2020 (awarded distinction). The images submitted for the FMP are part of a wider programme of work which seeks to explore community engagement with urban regeneration in east London though three forms of image making: (i) images made by residents in the exploration of their life-worlds, experiences and aspirations in changing urban environments; (ii) collaborative image-making with community and activist groups to build a repository of images for advocacy; (iii) my own images made as a personal (lyrical) response to regeneration projects in east London. The Covid-19 pandemic measures required substantial revision to the latter stages of the project. Considering the form that community focussed art might take in a post/perpetual pandemic world will be one of the themes addressed in my DFA related work.

The three sets of images submitted as FMP outcomes are from the third strand of image making: my own response to three areas undergoing extensive development in Barking. The public outcomes, in the form of a series of workshops, presentations, pop-up exhibitions and production of archive boxes of prints, maps, soundscapes, handmade books and documents, present these images in the context of the wider project and relate them directly to the places they explore. A principal objective in the development of this programme of work was to create a meaningful, challenging and productive context in which to learn and develop my practice through the production of a diverse range of forms of images, both individually and collaboratively. This is reflected in the ways in which I have chosen to present the work, which emphasises Wright’s (2018) notion of ‘usership’ (see Toward a Lexicon of Usership); a blurring of the distinction between producers and consumers which challenges established practices of spectatorship, expertise and ownership in the arts. I also sought to explore the materiality of prints and alternative ways of engaging with photographic work. Although the FMP focused on a specific locale, the project as whole addresses wider contemporary photographic and artistic practice.

I am applying for the DFA programme in order to develop my practice further in dialogue with other experienced practitioners from across the arts and other disciplines, and to continue to explore the relationship between theory (from a range of disciplines) and practice in the arts. I found dialogue with other practitioners in my MA programme very productive. In particular, I wish to bring my art practice and my professional and academic expertise and experience (particularly in relation to pedagogy, research and lifelong learning) closer together. UEL provides a particularly apposite setting for this work, as I live in Redbridge, have been selected for the London Creative Network Artist Development Scheme based at SPACE Ilford, and am carrying out work in Hackney, Newham and Barking and Dagenham (including the Shed Life project in Barking, in collaboration with UEL architecture students, and featured on the UEL website). I have links with arts and community projects in the outer boroughs of east London (for example, producing images for Eastside Community Heritage and the Thames Ward Community Project, and exhibiting at Everyone Everyday and Studio 3 Arts). I have close links with higher and further education in east London, for example as a governor of Barking and Dagenham College and as Chair of the Board of UCL Consultants. Through the DFA programme I hope to diversify, enrich and refine my practice and to produce a coherent and intellectually informed body of artistic work with particular relevance for the community, and to collaborate with others to make a tangible contribution to art practice at and around UEL.