I took part in three reviews. In each case I focused on the more experimental channel mixing work, to get some feedback on this and how I might develop it. I got useful comments from each session, and will think through how to respond to these constructively.

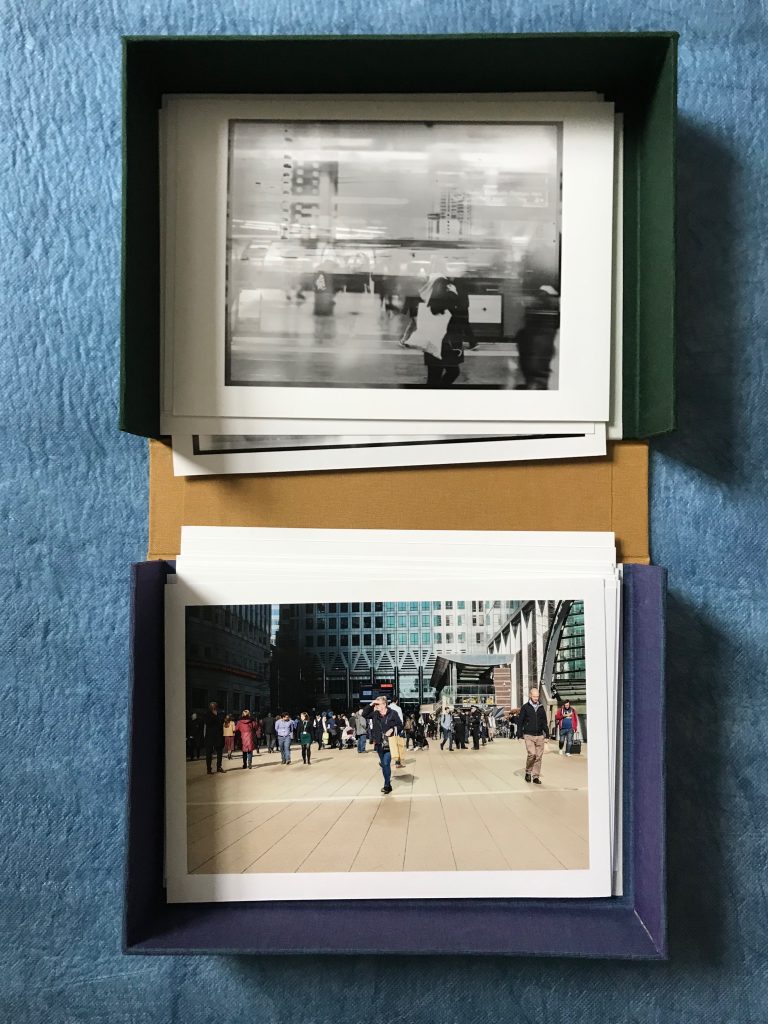

(i) Gary, Katerina and Clare. The focus in this session was on how to present the range of outputs from the regeneration work. Clare suggested a website. Gary suggested something more like an archive, which has physical presence, and whilst more difficult to access, is more difficult to destroy. My thoughts are that it might be possible to produce something that can be configured by others in different ways (according to their interest in the work). This resonates with my thoughts about using photography as a heuristic device (whilst critiques of the photography as representation abound, the alternatives proposed are either performative or introspective: photography as a heuristic offers a more social and potentially transformative alternative). Gary’s observation was prompted by my use of the archive box I made a London Book Arts, and I could certainly make a number of these in which to present prints (and this links with my focus on prints as artifacts). I’m also still considering handmade books. I need to look again at Christian Boltanski‘s work (I have one of the boxes he produced for the Whitechapel exhibition in the 80s). Other artists to follow up: Taryn Simon (suggested by Katerina), Andrea Luka Zimmerman (Haggerston Estate work, suggested by Clare), Mary Evans (on archives, suggested by Gary) and Mat Collishaw (suggested by all). We also discussed Forensic Architecture’s Turner Prize installation (see also my earlier post on the Turner Prize shortlist) and the use of timelines and time-codes. The overlaying of a map with historical settlements also holds potential for my work, I think. Could chart changes of use in the area over time, and link to other images and documents. This also links with the work with JustMap creating a community map of the Barking Riverside area.

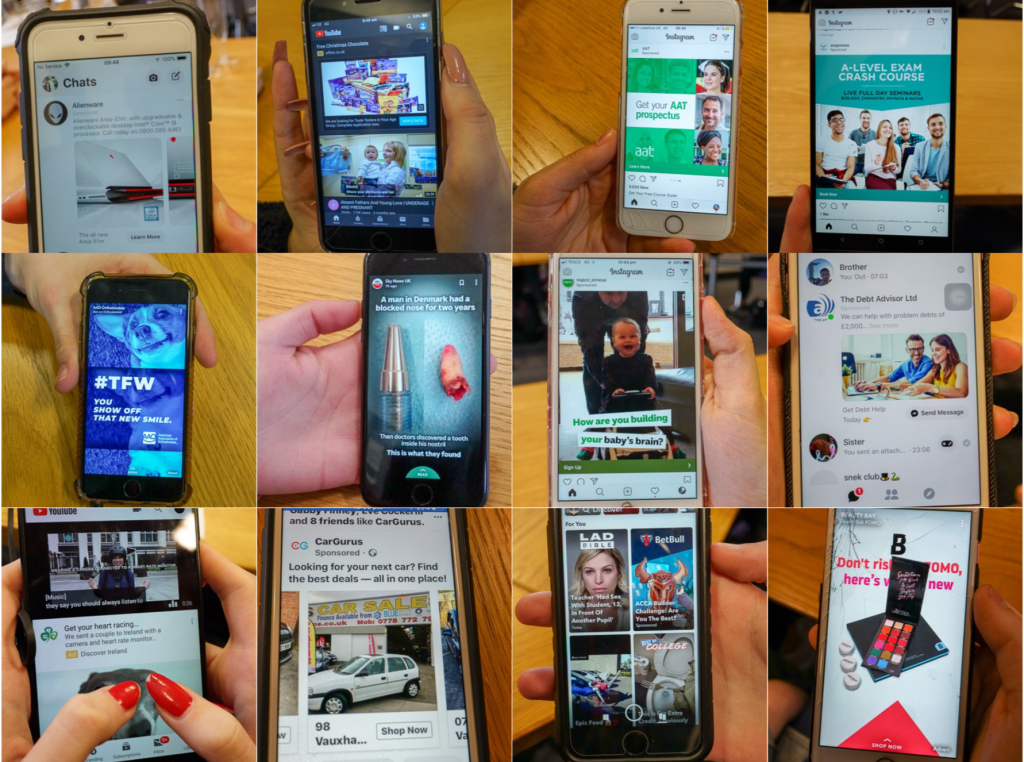

(ii) Steff and Michelle. I wanted to think about the form and content of my WIP portfolio in this session. Comments received reinforced the need to focus more tightly on a particular part of the project. Reflection on this has strengthened my commitment to focussing on the level of my own creative work produced in response to the my experiences and work in regeneration areas. I need to make sure that the intent in making these more experimental images is clear (there is a strong expectation, I think, that photographic work in these contexts should take a particular form, as explored in my earlier oral presentations). I think there is also a concern about the complexity of the images. Michelle expressed concern about the descriptiveness of the images and lack of clarity about what I wanted the viewer to feel, for instance, was the intention to present a dystopian or apocalyptic vision. She suggested zooming in on a parts of the image (maybe those where there is ambiguity) and consideration of the political dimensions of Robert Rauschenberg’s work (also, complexity). And another recommendation to look at Taryn Simon, as well as John Stezaker (collage, and complex images) and Brian Griffin (for instance, The Black Kingdom). The images presented are just exploration of process at this stage, so useful to think through this issue now, which I will do in a later post. If I continue with the channel mixing idea, I need to think about whether (and if so, how) the constituent images are presented alongside the ‘mix’ (or mixes), also discussed in this session. It is also possible to animate the mixes, bringing particular aspects of the image to the fore, which could address the concern about the focus of the image (which would change as the interaction between the images changes). And I could incorporate sound, as with the Roding Valley Park work. Others in the group agreed that the images might work best if printed large.

(iii) Wendy and Stella. I wanted to look forward to the FMP stage in this session. Wendy’s comments helped me to be more confident in the research dimension of the assessment of the FMP, and reinforced the the need to ensure that this was clearly articulated with the image making. We discussed the possibility of printing the images on perspex (or on acetate) as another way of invoking interaction between the images. Stella was concerned about the arbitrariness of the colour aspects of the channel mixing approach, which worries me too and which leaves me with monochrome images. I think that is fine, but I need to work through the rationale and effects of the process, perhaps in relation to the production of ‘fictions’ that project backwards and forwards from a point in time (to a constructed past and an imagined future). Am looking at Stella’s paper on Moire. Wendy confirmed that not all the work presented in the FMP has to be done in the two semesters, for instance, where the project is longer term and developing over the course of the programme. There must, however, be significant value added to the project over the course of the FMP (it can’t, for instance, be an existing body of work that is ‘tweaked’ in the FMP). The presentations by current FMP students at the conference were particularly useful in seeing how the FMP could develop.